Gainsborough's Blue Boy: The private life of a masterpiece

Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California

Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CaliforniaFew other paintings in art history have become such a powerful symbol of non-conformist gender identity and same-sex attraction, writes Matthew Wilson.

A record number of visitors queued outside the National Gallery in January 1922, despite the drizzly conditions, to see a single painting: Thomas Gainsborough's Blue Boy (c 1770). The artwork was bought by a US collector in 1921 and its imminent departure drew 90,000 people to get a last glimpse what the press had dubbed "the world's most beautiful painting". An article in the London Times claimed that the Blue Boy exemplified the "courtly grace and serene carriage of a people who knew themselves a great people and were not ashamed to own it." To the general population, Gainsborough's Blue Boy was the epitome of high culture and the noble British character.

In January 2022, Blue Boy is making a centenary comeback to the UK and will once again be displayed in the National Gallery, now for a five-month run. But how many visitors this time around will know about the painting's private life as a symbol of gay pride?

Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California

Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CaliforniaMore like this:

- Unlocking the hidden life of Frida Kahlo

- Portrait of a complex marriage

- Paintings of 'rage, rebellion and pain'

Valerie Hedquist, a professor of art history at the University of Montana, has written extensively about the painting and its role as a gay icon. It is partly a tale of unintended consequences, and how artists cede control of their creations once they are absorbed into the public arena. Hedquist tells BBC Culture that when Thomas Gainsborough painted Blue Boy in around 1770 "it was most likely a demonstration piece to show off his talents". The boy is believed to be the artist's nephew, Gainsborough Dupont, dressed in a 17th-Century aristocratic costume as an act of homage to Sir Anthony van Dyck, an artist whose techniques and compositions Gainsborough admired.

The National Gallery, London

The National Gallery, LondonBack in 1770, the pose of Blue Boy would have struck people as noble, signalling an exemplary future husband and father. He is standing in an authoritative position known as contrapposto, much used in classical art. The jutting elbow is another well-used pose in European portraiture, described by art historian Joaneath Spicer as "indicative essentially of boldness or control – and therefore of the self-defined masculine role."

The Minneapolis Institute of Art

The Minneapolis Institute of ArtBut for Hedquist, the idea that the boy in the painting is dressing up in costume and acting is critical to his later reappraisals: "the Blue Boy invites performance," she says.

This began on stage in the 19th Century, where actors playing "Little Boy Blue" in pantomimes were frequently dressed up in the silks, breeches and lace collar of Gainsborough's Blue Boy. And these actors would frequently be girls. This, for Hedquist, was the start of the "feminisation" of Blue Boy. "By the latter part of the 19th Century," she explained, "the magazines are just filled with pictures of girls dressed as Blue Boy."

In 1922, the year that Gainsborough's painting found a new home in the US, Cole Porter performed his musical Mayfair and Montmartre, in which Nelly Taylor dressed as Blue Boy and theatrically emerged from a frame singing a song called Blue Boy Blues. Marlene Dietrich dressed as Blue Boy for a comedy revue in Vienna in 1927, and Shirley Temple did the same for the film Curly Top in 1935.

Getty Images

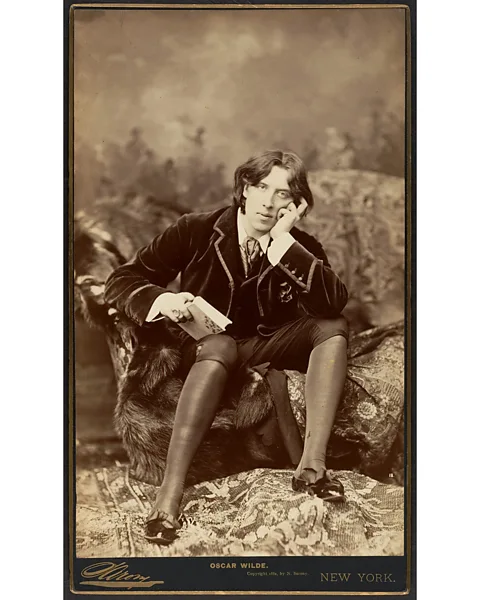

Getty ImagesThe painting had created a platform for gender identity to become blurred – Blue Boy could be either masculine or feminine in the fluid world of theatrical performance. According to Hedquist, another dimension to the story concerns the writer and leader of the Aesthetic Movement, Oscar Wilde. Wilde dressed in extravagant historically inspired clothing, frequently with knee-breeches, velvet jackets, cloaks and broad-brimmed hats in homage to painters like Gainsborough. In one photograph taken by Napoleon Sarony in 1882, Wilde, in swanky buckled shoes and knickerbockers, struck the exact pose of Blue Boy.

When Wilde was imprisoned for his homosexuality on charges of gross indecency in 1895, he became the most famous publicly gay man in the world – and the photographs of him by Sarony were misappropriated. According to Hequist, "they eventually ended up in the first medical books that were teaching people how to recognise homosexuality". It embedded a savagely intolerant view of same-sex attraction, based closely around the stereotyped visual "tells" of Blue Boy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter Blue Boy arrived in the US, it became famous, appearing on ceramics, textiles and thousands of reproduction prints. How it was interpreted by its new host nation was also subject to the winds of cultural change. According to Hedquist, a formative episode was the so-called "lavender scare" in the 1950s in which gay men and women were perceived to be threats to national security and were hounded from government office. Common stereotypes of gay deportment – now laughable in their ignorance – such as lacy cuffs and fancy shoes, were cited as signifiers of these "enemies within".

A visual shorthand

It led to sinister comedic parodies of perceived gay behaviour in popular culture, with outlets including cartoon strips. In Mad Magazine in September 1970, one cartoon featured a character called Prissy Percy, who is teased by a group of sporty, all-American boys – the final scene reveals Percy to be Blue Boy. The cartoon's covert message and sentiment is homophobic; Hedquist sees it as Blue Boy's first "outing". A Dennis the Menace cartoon published in 1976 also featured the Blue Boy, where he was again labelled a "sissy".

"The emerging ideas about how people see gay men is so important to how the Blue Boy becomes an iconic image," says Hedquist, "first of all as a source of ridicule and then as a reappropriation."

The reappropriation came in the form of a gay magazine first published in 1974, called "Blue Boy". The cover of the first issue featured a photo of Dale, a boxer from Ohio, in a homage to Gainsborough's masterpiece, albeit without any trousers and a conveniently repositioned hat. The magazine, brainchild of entrepreneur Don N Embinder, continued publishing until December 2007, and advertised products and services whose recurrent symbol was the Blue Boy. It recommended gay-friendly hotels and bars and fostered a sense of community. "The first gay travel agency was called 'Blue Boy'," Hedquist explains. "They had cruises and hotels where men could be openly gay, wearing 'Blue Boy' T-shirts and carrying 'Blue Boy' travel bags. It was a full reappropriation and a celebration that the Blue Boy was gay." In the period after the Stonewall riots, this was a galvanising symbol, and has left a legacy of multiple "Blue Boy" gay bars around the world.

Kehinde Wiley/The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Kehinde Wiley/The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical GardensIt also had an effect on visual art. US artist Robert Lambert created collages of photocopied imagery and sent them via mail to his friends, some of which included the Blue Boy as a signifier of his sexuality. Blue Boy was appropriated frequently by the US ceramicist Howard Kottler, a choice that expressed “explicit homosexual references”, according to art historian Vicki Halper. But the most explicit references to the Blue Boy came in the work of another US ceramicist, Léopold Foulem: according to Hedquist, he "transformed the tentative allusions to gay content found in the work of Lambert and Kottler into a full-blown riot of queer significance" with his highly provocative scenes of the Blue Boy in trysts with characters like Father Christmas and Colonel Sanders.

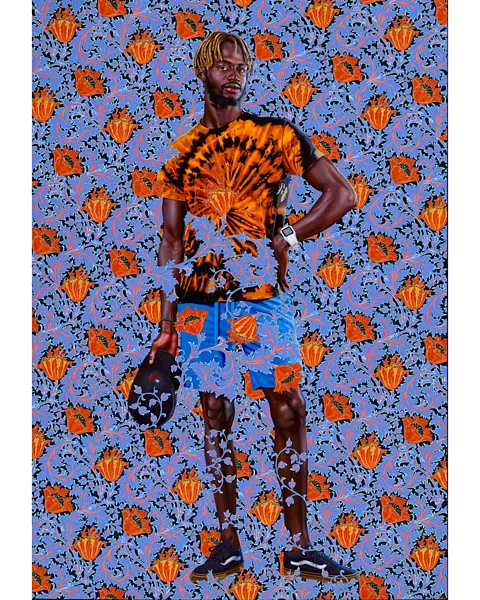

Other artists who have identified as gay, such as Robert Rauschenberg and Kehinde Wiley, have cited Blue Boy as a major influence on their later output, with Wiley having recently created a direct homage that is currently on display at the Huntington Art Museum in California (in 1921, Henry and Arabella Huntington bought The Blue Boy from the art dealer Joseph Duveen, who had acquired it from the Duke of Westminster).

Wiley's painting, showing a 21st-Century Blue Boy with dyed blond dreadlocks, Apple watch and baseball cap, marks the culmination of a two-centuries-long journey of Gainsborough's original from a pillar of traditional cultural values to gay icon. According to Hedquist, Blue Boy is a game-changing symbol in the history of gay rights. Apart from its appeal to gay artists, its use as a branding emblem in Blue Boy magazine in the 1970s seemed to have a resounding historical significance. "It was the first opportunity of a life that was open and acceptable," she says. "It provided a means of leading a full public existence as a gay man – and it all came through Blue Boy."

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.