'He was going to shoot me': The 1970s sex scandal that led to a dramatic trial

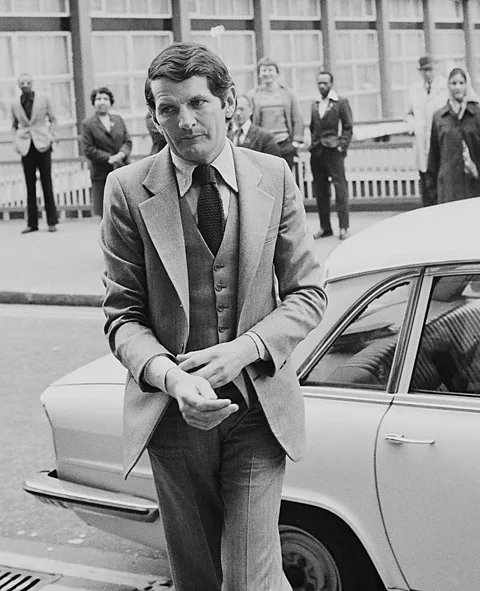

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen the leader of the UK's Liberal Party, Jeremy Thorpe, had an affair with a male model, insiders in Britain's political and security elite kept quiet about it. But when Thorpe's former lover blurted out the truth in court, it was the beginning of a story wilder and more astounding than anyone could have imagined.

An illegal gay affair, a botched plot and a dead dog were at the heart of what the British press would dub "the trial of the century". At its centre was Jeremy Thorpe: Liberal Party leader, a pillar of the establishment and the first British politician to be tried for conspiracy and incitement to murder. The story became public on 29 January 1976 when, during a minor court hearing, his former lover Norman Scott shouted: "I am being hounded by people the whole time because of my sexual relationship with Jeremy Thorpe." The pair were portrayed in 2018 BBC drama A Very English Scandal by Hugh Grant (as Thorpe) and Ben Whishaw (as Scott). Scott's bombshell revelation was the first bit of legal theatre in a stranger-than-fiction tale whose details would only get increasingly bizarre.

Thorpe was educated at the elite Eton College, where he told friends his two big ambitions in life were to become prime minister and to marry Princess Margaret. For the privileged and well-connected teenager, neither of these fantasies was too far-fetched. Later, as a law student at Oxford University he made an impression both through his flamboyant Edwardian-style clothes and his talent as a charismatic debater. After graduating he became a barrister and television presenter, but his political ambition continued to smoulder. A gifted mimic and born showman, in 1959 he was elected as a Liberal MP at the age of 30.

With this pedigree he seemed destined for the very top, yet behind the public façade he was secretly gay at a time when male homosexuality was illegal. As well as facing widespread moral condemnation, the harsh penalties involved before the law changed in 1967 left those living clandestine lives vulnerable to blackmail. For an aspiring prime minister, the consequences of being exposed would be devastating. But Thorpe loved the risk-taking involved, and had a string of short and casual affairs. In the summer of 1961, he encountered an aspiring young model from a humble background who would prove impossible to cast aside.

Looking back in 1977, Norman Scott told the BBC how they first met "literally over a stable door". In those days, Scott went by the name Norman Josiffe and was employed to look after horses owned by a professional showjumper. He said that Thorpe "seemed a sort of warm character" and they began meeting regularly. With Scott perpetually broke and struggling with mental health issues, they made an odd couple. When Scott was arrested for alleged shoplifting, Thorpe spoke up for him to detectives. He gave Scott access to his expense accounts at upmarket London clothes shops and introduced him to his well-heeled friends. While Thorpe seems to have discarded any correspondence between them, his affectionate but incriminating letters were treasured and held as evidence by Scott.

Ironically, it was the increasingly erratic Scott who broke off the affair. He said: "I told this mutual friend of ours that I was going to stop this whole thing. I didn't know how, but it was just too much for me. I couldn't cope. I was going to destroy him and myself." Alone and near despair, he began to speak openly of killing Thorpe and then taking his own life. A worried friend contacted the police. In interviews with officers, Scott incriminated himself by confessing he had been in a relationship with Thorpe. Not only that, he also had the paper trail to prove it. But who would believe this seemingly unstable man making these outlandish claims about such an eminent figure?

Sex and spy scandals

It turned out that the security services already had confidential files detailing Thorpe's compromised private life, but none of the allegations were formally investigated. In a 2014 radio documentary, BBC current affairs reporter Tom Mangold observed that rather than any explicit cover-up, all the inaction was "founded on quiet understandings and implicit assumptions inherent in British society" at the time. In the early 1960s, Britain was being rocked by a series of sex and spy scandals. There had already been the case of John Vassall, a gay civil servant who spilled British state secrets to the Soviets under threat of blackmail. Soon afterwards there was Minister for War John Profumo's affair with Christine Keeler, a young model who was simultaneously involved with a Russian spy. The last thing the British establishment wanted was yet another scandal, this time involving a rising parliamentary star.

Scott would not be deterred by this institutional stonewalling, and wrote to Thorpe's mother. "I thought she knew about our relationship," Scott later insisted to the BBC. While not a blackmail letter, it made implications that horrified Thorpe when he intercepted it. The letter was proof that Scott was turning from a nuisance into a threat. Thorpe confided in his friend and fellow Liberal MP Peter Bessell, who agreed to meet Scott and "try to sort out his difficulties for him". In 1967, after just eight years in parliament, Thorpe became party leader, promising to turn the Liberals into a radical pioneering force. It became more important than ever to ensure that Scott stayed quiet. Bessell arranged to pay him a small weekly retainer and tried to find him a job. But Scott wasn't satisfied.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBoth men had complicated personal lives. Thorpe married Caroline Allpass in 1968 and they had a son together. She was killed in a car accident shortly after the 1970 general election. In 1973, he married Marion Stein, aka the Countess of Harewood, a formidable Austrian-born concert pianist who would remain loyal to the end. Scott married Sue Myers in 1969; they had a son but separated soon afterwards.

More like this:

• The 1960s sex scandal that rocked British politics

• The shocking downfall of Margaret Thatcher

• The homosexuality report that divided the UK

While Thorpe continued to thrive in his high-profile career, more than 10 years after their liaison Scott continued to brood in the shadows and pester anyone who would listen to his story. The allegations eventually reached the office of Liberal MP Emyln Hooson, who unlike Bessell was concerned enough to inform senior colleagues. An internal party inquiry concluded that the case against Thorpe had not been proved. On the eve of the February 1974 general election, an associate of Thorpe paid Scott £2,500 to hand over those pesky letters that contained so much incriminating evidence. That election would be the pinnacle of Thorpe's political career. His party won enough seats that it looked briefly like he might become a government minister in a coalition government, although a deal could not be reached.

A plot is hatched

Those whispers about Thorpe refused to go away. Whether the idea emerged from idle chit-chat among Thorpe and his friends or from a more sinister discussion, a plot was hatched to intimidate Scott, at the very least. Thorpe's associates contacted Andrew Newton, a rather louche airline pilot and unprofessional hitman. Newton befriended Scott in October 1975 by claiming he was a private detective hired to protect him from someone planning to kill him. He talked the trusting Scott into going for a country drive in the dark. Newton brought a gun while Scott brought his dog, an excitable Great Dane called Rinka.

When they pulled over on a remote stretch of road, the dog bounded out of the car. Scott recalled in 1977: "She was barking and jumping about. And then he just shot her. And I then... I tried to make her come to life again. I was bending down and he said, 'It's your turn now.'" Scott stared at him in disbelief as Newton stood trembling in front of the car headlights with the gun in his hands. "He levelled it at me… and I suddenly realised he was going to shoot me as well," said Scott. But the gun jammed and Scott lived to tell the tale. Newton ended up being sentenced to two years in prison. At his trial, he claimed Scott had been blackmailing him over a nude photograph.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Sign up to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

Three months after this terrifying ordeal, Scott was up in court on a minor welfare fraud charge. It was there, on 29 January 1976, that he shouted about his "sexual relationship with Jeremy Thorpe". Because Scott had made his claim in open court, journalists were protected from libel laws and were free to report his allegation. The Thorpe affair was in the public domain at last.

Thorpe issued an immediate denial, but in May, things went from bad to worse for him when Peter Bessell, his formerly loyal Liberal Party friend, decided to tell all. "We moved from an area of a private cover-up of somebody's private life, into an area where it was now a cover-up of an attempt at murder," Bessell later told the BBC's Panorama. As the story escaped out of his control, Thorpe agreed to allow the Sunday Times to print an affectionate letter he had written to Scott back in 1962. While the more liberal social attitudes of a different decade may have allowed Thorpe to fight on, he decided to resign as party leader.

The story took yet another twist in October 1977 when the London Evening News ran the sensational headline, "I Was Hired to Kill Scott." Fresh out of prison, Newton recanted his blackmail defence and was now claiming he was paid £5,000 as part of what the paper described as a "sinister conspiracy involving a leading Liberal supporter". Nine more months of police investigation led to Thorpe and three associates being charged with conspiring to murder Scott. It was dubbed by the press "the trial of the century". At Thorpe's request, it was postponed for eight days so that he could fight for his parliamentary seat in the May 1979 general election. He was heavily defeated.

At the end of the trial, the judge delivered what BBC Panorama's Tom Mangold described as "one of the most astonishingly partial summing-up speeches ever to a jury". Mr Justice Cantley said that because the three main prosecution witnesses had struck lucrative deals for selling their stories to the press upon conviction, their testimonies had been tainted. Bessell, said the judge, was "a humbug" while Newton was "a buffoon, perjurer and almost certainly a fraud". As for Scott, he was labelled "a crook, fraud, sponger, whiner and parasite".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy contrast, Thorpe was "a national figure with a very distinguished public record". In the judge's summing up, skewered memorably by the comedian Peter Cook, he directed the jury that if there was any reasonable doubt that Thorpe planned to kill Scott, they must acquit. The verdict was not guilty. Speaking later with his steadfast wife Marion beside him, Thorpe said: "I have always maintained that I was innocent of the charges brought against me, and the verdict of the jury, after a prolonged and careful investigation by them, I regard as totally fair and a complete vindication."

Following the trial, Scott retreated from the limelight. In 2022 at the age of 82, he released his autobiography, titled An Accidental Icon. As for Thorpe, he retired from public life while maintaining his innocence to the end. He died in 2014. In a Guardian interview in 2008, Thorpe reflected on the affair: "If it happened now, I think... the public would be kinder. Back then they were very troubled by it. It offended their set of values."

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.