The bomb sites hiding in plain view

BBC

BBCAs dawn broke on the first full year of peace since the start of World War Two, the people of Hull faced the huge task of rebuilding a city devastated by bombing. Eighty years on, the scars still remain.

When Rob Haywood moved into his smart terraced home in east Hull in the 1970s, he had no idea it had been bombed.

"A neighbour said as a boy he used to play here during the war and there was a huge bomb crater where our tenfoot [alleyway] is," he recalls. "Every winter it filled up with water and he went skating on it."

Today, only a slight dip remains to mark where a landmine exploded on 18 July 1941, blowing away much of Rob's house and those around it.

The family who lived there at the time – a mum, dad and their 18-year-old daughter – died.

"I was told part of an air raid shelter was found on top of a roof about 100 yards away," says Rob. "It's very sad."

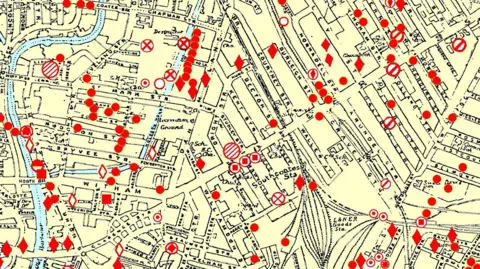

The spot where the landmine fell is marked on the Hull Bomb Map, an online resource Rob has maintained for two decades, plotting the fall of every bomb dropped over Hull during World War Two.

Rob, a local history enthusiast who volunteers at the Sutton and Wawne Museum, digitised the map from an older physical version compiled after the war.

When people come across it, naturally they look for where bombs fell near their own homes, he says.

Some of the sites can still be seen today, betrayed by gaps between rows of properties, where the house numbers jump by four or six.

Rob Haywood

Rob HaywoodRob, who is originally from Leicester, moved to Hull in 1973 and began driving buses. One of his first routes was the 56 to Longhill.

"I'd be driving up and down Holderness Road and seeing all these bomb sites that became garages or car lots or timber stores," he recalls.

More than 140 people died in the raid that hit his home, according to the Civilian War Dead Roll Of Honour.

It devastated communities around Holderness Road and the Reckitt's works and several streets still bear the scars.

In Mulgrave Street, where several air raid shelters were hit, swathes of green grass mark where terraced homes stood.

In New Bridge Road, a "once busy and thriving little shopping area" was "reduced to a smouldering heap of rubble", according to one survivor whose story was printed by the Hull Daily Mail in 1990.

"Gone was the Sherburn cinema where I used to spend many a happy hour, the beer-off shop at the corner and the wet fish shop," they said.

"A little further along, the local dry cleaners was in ruins. I learned later the whole family of six had perished."

There were more than 80 raids during the war, killing about 1,200 people and injuring 3,000. Analysis of contemporary records suggests between 4,000 and 5,000 homes were destroyed or damaged beyond repair, while swathes of the city centre were flattened.

While some streets were patched up – Rob's house was rebuilt in 1948 – others were cleared as part of an ambitious plan to modernise the city, put forward by town planners Edwin Lutyens and Patrick Abercrombie.

They envisaged moving tens of thousands of people from inner-city slums to modern estates and remodelling the city centre with pedestrian-only shopping precincts and a new road network.

One proposal involved building a flyover next to the home of Hull's most famous son, the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce, in the historic Old Town.

This might seem in terribly bad taste now, but according to Dr James Greenhalgh, a historian from the University of Lincoln, there was a feeling "that we wanted to move on and make new things".

National Library of Scotland

National Library of ScotlandDr Greenhalgh led a two-year study, The Half Life of the Blitz, which gathered the stories of citizens from wartime to the present day.

He believes, by and large, that the rebuilding of the city was pretty successful.

"The council thinks that they need at least 12,000 new houses. And so for that reason, they bring these two planners in," he says.

"There's a lot of debate among historians about how far the plan was meant to be achieved. It's kind of a very grand vision.

"The one thing they do manage to do a lot of is the housing. So there's big, big estates that are built."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAmbitions for a new-look city centre were less successful as money and building materials ran out.

"The city centre is the hardest part because there's lots of different interests at work," Dr Greenhalgh says.

"The corporation [now Hull City Council] tries to get control of the land and fails.

"Instead of holistically redeveloping the entire city centre, what wins out is a much more piecemeal."

Notable buildings were completed within a decade, including the Hammonds department store and the Queens House retail precinct in Paragon Street, but other sites, such as the Royal Institution museum in Albion Street, were cleared but never properly redeveloped.

It also meant the Old Town, now seen as the jewel in Hull's architectural crown, was "kind of accidentally left", Dr Greenhalgh says.

"As we went through the process of building modern city centres, and perhaps they didn't turn out to be what we wanted them to be, I think people came to value those older buildings much more."

One building very much valued today is the National Picture Theatre, in Beverley Road. It was partially destroyed on 18 March 1941 and is now the last remaining bomb site with visible ruins.

In the decades after the war, numerous schemes to demolish or redevelop the cinema failed to get off the ground – another happy accident.

After a long campaign, it is now being restored as an events space and memorial.

More than eight decades on, it will provide a fitting tribute to those killed during Hull's darkest days.

Listen to highlights fromHull and East Yorkshire on BBC Sounds, watch the latest episode of Look Northor tell us about a story you think we should be coveringhere.

Download the BBC News app from the App Store for iPhone and iPad or Google Play for Android devices