'A gasp of wonderment escaped our lips': The dazzling discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb

Alamy

AlamyIn a BBC archive clip from 1936, the archaeologist Howard Carter describes the moment on 12 February 1924 when he and his team became the first people in 3,300 years to meet the Egyptian boy king.

"Thirty-three centuries had passed since human feet last trod the floor on which we stood, and yet the signs of recent life were around us."

Ninety years on, Howard Carter's clipped English voice sounds itself almost like an ancient relic. When he spoke on BBC radio in 1936, 14 years had gone by since he first uncovered the treasure-rich tomb of Tutankhamun. The almost miraculous discovery by Carter and his expert team of the boy king's intact tomb had made him world-famous and sparked a craze for all things ancient Egyptian.

Speaking on a programme reviewing the events of 1924, he conjured the uncanny sensation he felt on 12 February that year when they finally reached Tutankhamun's sarcophagus, the stone coffin where the pharaoh had lain undisturbed for millennia. When he notes details such as "a half‑filled bowl of mortar, a blackened lamp, the chips of wood left on the floor by a careless carpenter", his sense of wonder comes through as alive as ever.

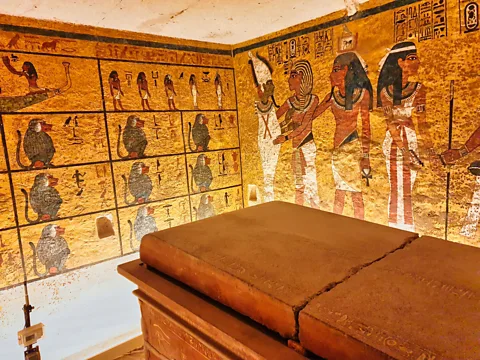

"We had penetrated two chambers, but when we came to a golden shrine with doors closed and sealed," he said, "we realised that we were to witness a spectacle such as no other man in our time had been privileged to see." He removed the precious seal and opened the door to reveal a second shrine "even more brilliant in workmanship than the last".

When the door swung open slowly, he was confronted by an "immense yellow quartzite sarcophagus". There was no way forward without raising its stone lid that weighed about 2,500lb, or 1,130kg. An audience of VIPs and dignitaries watched as an intricate pulley system raised it. When Carter removed the stone, light shone into the coffin. "A gasp of wonderment escaped our lips, so gorgeous was the sight that met our eyes," he said. "A golden effigy of the young king of magnificent workmanship filled the whole of the interior; this was but the lid of a series of three coffins, nested one within the other, enclosing the mortal remains of the young King Tutankhamun."

Despite going on to make one of the world's greatest archaeological discoveries, Carter had left school at 15 and had no formal training. With his talent for drawing, a local aristocratic family who lived near his rural Norfolk home took the solitary teenager under their wing. The Amhersts' Didlington Hall had the greatest private collection of Egyptian objects in Britain, and he became fascinated by their stories. At 17, his artistic skill secured him work in Egypt as a draughtsman and tracer. He arrived during a boom for archaeology, much of it funded by wealthy amateurs and British aristocrats. For more than two decades he trained on the job.

The staggering discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb owed much to good fortune. Carter had been toiling away with little success for years in the Valley of the Kings, an area just west of the Nile used by the ancient Egyptians as the main burial ground for the pharaohs. The tomb entrance had long been concealed by layers of ancient debris, keeping it beyond the reach of both grave robbers and archaeologists.

The cult of King Tut was born

The breakthrough came in November 1922 when Carter held up a candle and peered into the darkness through a small hole chiselled in a door. Waiting nervously nearby, his wealthy patron Lord Carnarvon asked if he could see anything. The legend goes that Carter replied, "Yes, wonderful things." He wrote in his excavation diary: "As my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room emerged slowly from the mist. Strange animals, statues and gold. Everywhere the glint of gold."

All this treasure was intended to accompany Tutankhamun into the next life. The 11th pharaoh of Egypt's 18th dynasty, Tutankhamun was aged about 17 when he died. It is thought that he inherited the throne at the age of eight or nine. The cause of death remains uncertain, with theories ranging from assassination to a hunting accident.

Alamy

AlamyThe November 1922 find was only the start of it, revealing what Carter described as the antechamber, a small outer room. It took another 15 months for the team to reach the sarcophagus. When the Times newspaper published its world exclusive about "what promises to be the most sensational Egyptological discovery of the century", the cult of King Tut was born. Egyptomania swept through the 1920s, inspiring everything from fashion and Art Deco design adorned with pyramid and lotus-flower motifs, to silent films and jazz songs. Carter and Carnarvon became international celebrities.

However, just a few months after the big reveal, Carnarvon's luck ran out when he died of blood poisoning from an insect bite. His death gave the Tutankhamun story a new lease of life, with tales of the mummy's curse and Tut's revenge adding to the growing myths around the discovery.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Sign up to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

All this was happening amid political upheaval in Egypt. The country had been occupied by British forces since 1882, but in early 1922 it gained partial independence. Carter was working courtesy of the Egyptian government, which expected the finest antiquities to go to Cairo, its capital city. An irascible character, he had an often-antagonistic relationship with the Egyptian Antiquities Service which oversaw his excavation work. Tutankhamun became a symbol of the country's struggle to escape colonial influence, and many Egyptians who had shared their knowhow and local knowledge were written out of the story. As well as the labourers who cleared the tomb site, Carter also worked with skilled foremen such as Ahmed Gerigar, Gad Hassan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed Said.

More like this:

• The heist to reclaim the ancient Stone of Destiny

• The first men to conquer Everest's 'death zone'

• The ancient monuments saluting the winter solstice

Tutankhamun's mummified body remained in the Valley of the Kings, but many of its other treasures were moved initially to the Cairo Museum. Among them were two trumpets, one silver and one bronze, that would feature in 1939 on an extraordinary BBC radio programme. Pioneering radio producer Rex Keating managed to persuade the Egyptian Antiquities Service to let the BBC broadcast a sound that had gone unheard for three millennia. In a 2011 BBC documentary about the transmission, archaeologist Christina Finn said: "The idea of actually playing a 3,000-year-old trumpet wouldn't be entertained today, but in the gung-ho archaeological heyday of the early 20th Century, there were few such qualms."

The musician chosen to perform for an estimated 150 million people worldwide was bandsman James Tappern. Before he began, Keating cautioned listeners that neither trumpet was easy to sound. He did not need to worry, as the haunting sound of both ancient instruments came through loud and clear. A relieved Keating concluded the programme with dramatic flair. "After a silence of over 3,000 years, these two voices out of Egypt's glorious past have gone echoing across the world," he said. Carter did not live to hear that broadcast, having died of cancer weeks earlier at the age of 64.

Tutmania was reborn in the 1970s with the international success of the Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition. Its star attraction, the gold mask, drew more than 1.6 million visitors to the British Museum in 1972, still its most popular ever exhibition. The show then travelled to the Soviet Union for two years. After that, it toured six US cities between 1976 and 1979, where it was such a sensation that it inspired superstar comedian Steve Martin's funky novelty song King Tut. In a deadpan voice, he told the Saturday Night Live audience, "I think it's a national disgrace how we've commercialised it with trinkets and toys, T-shirts and posters," before performing a goofy dance parody.

The complete tomb on display at last

From popular culture to serious academic inquiry, the story of Tutankhamun continues to fascinate. More than a century after the first discovery, the items found in the tomb still have mysteries to be unravelled. The University of Oxford's Elizabeth Frood told the BBC's In Our Time in 2019 that less than a third of objects found in the tomb had been analysed fully. "We're talking something like well over 5,000 individual objects, and I think it's overwhelmed the subject a bit," she said. "It's really difficult to know how to manage certain object classes in the group because there's nothing like it."

In 2025, the complete contents of the tomb were finally put on display in a new museum near one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza. Dr Tarek Tawfik, former head of the Grand Egyptian Museum, told the BBC: "I had to think, how can we show him in a different way, because since the discovery of the tomb in 1922, about 1,800 pieces from a total of over 5,500 that were inside the tomb were on display. I had the idea of displaying the complete tomb, which means nothing remains in storage, nothing remains in other museums, and you get to have the complete experience, the way Howard Carter had it over 100 years ago."

The golden mask of Tutankhamun is in the museum, but his mummy remains at rest in the Valley of the Kings where the awestruck Carter and his team had encountered so many "signs of recent life".

In Carter's BBC broadcast, he noted how a tiny wreath of flowers laid on the golden outer lid of the sarcophagus was possibly "the last farewell offering of the widowed girl queen to her husband".

"Among all that regal splendour, there was nothing so beautiful as those few withered flowers. They told us what a short period 3,300 years really was."

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.