'You can't grasp her or replicate her': Why Anna Magnani is the overlooked 'goddess' of Italian cinema

Alamy

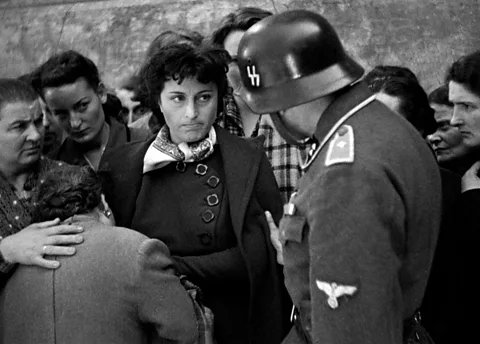

AlamyAnna Magnani's captivating performance in the masterpiece Rome, Open City, which is 80 this year, is a standout role that made her one of the country's finest talents.

If you asked the average person outside of Italy to name a legendary Italian actress, it's likely the answer would be Sophia Loren, not Anna Magnani. Yet Magnani is one of Italy's greatest performers. She won a best actress Oscar for her role in The Rose Tattoo (1955) – the first Italian to win the award. Marlon Brando was intimidated by her. Meryl Streep called her a "goddess". The New York Times called her "superb" and "the tigress of Italy's screen". Still, many today are unfamiliar with the "undisputed queen of Italian cinema".

Magnani is the protagonist of Roberto Rossellini's Rome, Open City (1945), a landmark in cinema history, whose 80th anniversary this year offers the chance to explore the reasons behind this apparent glitch in collective memory. Shot in January 1945, among the rubble of World War Two, the story takes place in the "long winter" of Nazi occupation, between the autumn of 1943 and the spring of 1944."Rossellini used scraps of expired film, stole power outlets from the Americans, shot in basements and locations without permits. And… he created a masterpiece," film historian Flavio De Bernardinis tells the BBC.

Alamy

AlamyInspired by the real stories of two priests executed by the Nazis, and co-written by the director, Sergio Amidei, Alberto Consiglio and a young Federico Fellini, Rome, Open City is a powerful film about the horrors of occupation and the courage of common people. "It's a political movie. Its goal was to show a good Italy – not the fascist, colonialist Italy. A country of good people," says Caterina Capalbo, the author of a book on the film, Roma Città Aperta. At the time, Mussolini and Hitler were still alive, so when the priest in the film utters the line, "And if they come back?", he is voicing a real preoccupation shared by the film's cast and crew.

Pina (Magnani) is the moral compass of the first half of the film. She is a middle-aged widow, expecting a child by her next-door neighbour, a partisan whom she loves and plans to marry the next day. She is intelligent without having an education; poor and generous, with a clear sense of justice without being righteous. She is a woman depicted with admiration, warmth, and with a realism that is rare in cinema – then and now.

"Finally, after years of cinema where everything was fake, perfect, pretty, this was the story of a real woman, not a diva, but someone who could be anyone," says actress Olivia Magnani, Anna's granddaughter, whose godfather was Roberto Rossellini and who grew up in houses where "the Oscar was on the shelf, among letters from Bette Davis and Jean Cocteau".

An iconic performance

Magnani was a successful 37-year-old theatre actress who hadn't been cast in lead roles in films because, as Olivia puts it, "she didn't have a tiny nose and blue eyes. She wasn't considered photogenic." Her first husband, director Goffredo Alessandrini, didn't believe she had a face for cinema.

Her pitch-black hair and fiery eyes contributed to the myth of her exotic origins. There were rumours that she was Egyptian. "Maybe she initially spread that myth too," adds Gianfranco Angelucci, a collaborator and friend of Fellini, "to be mysterious." In fact, Magnani, endearingly known as "Nannarella", was born at Porta Pia, in the heart of Rome, and never met her father. Her mother left her and moved to Egypt, possibly contributing to the confusion about her ethnicity, and leaving a void that Magnani turned into art.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I realised I wasn't born an actress," she wrote later in life. "I had simply decided to become one in my cradle, between one tear too many and one caress too few. All my life, I screamed with everything I had for that tear, I begged for that caress."

When Rossellini cast her in Rome, Open City, Magnani was a variety actress, as popular as an acclaimed stand-up comedian today. "The public in those theatres was tough. They threw dead cats at bad actors," says De Bernardinis. The dead cats, he swears, are not a metaphor: people would literally pick them up on the street. That's how Magnani learned to act for the theatre crowd. "You see Marlon Brando next to her [in 1960's The Fugitive Kind]. He is aware of the camera, looking for the light, making those faces and affectations. Magnani doesn't give a damn; she is immediate. She goes straight to the audience."

Many scenes in Rome, Open City were shot just once, because there wasn't enough film for second takes. Magnani said that they didn't rehearse the iconic sequence in which Pina runs after the Nazi van that is taking her Francesco away and is shot in the back. "With Rossellini, you didn't rehearse," she told Arianna magazine in 1970. "He created the scene. I came out of that door, and… I was transported back to the time when young men were taken away… Suddenly, I wasn't myself. I was the character."

Less than a year earlier, Teresa Gullace, a six-month-pregnant mother of five had been shot in Rome by a Nazi soldier after she waved at her captive husband. In the film, Francesco shouts "Teresa", as an homage. At the time, Magnani was also suffering, as her son had contracted polio.

An unconventional star

Magnani's communication of this raw pain on screen is perhaps one reason why she is less popular in the US today than other iconic Italian actresses. "Anna is the embodiment of a country that came out of the war with the courage of showing its wounds," says De Bernardinis. "Soon after, Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida and other 'maggiorate' ('busty actresses') represent the Italy that wants to forget the war. Florid, full bodied, flourishing."

Rome, Open City became the highest grossing film in Italy that year, and the first non-American film to earn over $1m in the US. The American press loved it. Magnani, The New York Times wrote, had "an ability to weep real tears, to laugh real laughter, to brawl fiercely; to be thunderous in anger, lusciously sensual in love". Tennessee Williams tried to convince Magnani to act in his new play on Broadway – one of the many American offers she refused. "This woman, Anna Magnani, she sinks the claws in the heart," he said.

Ingrid Bergman liked Rome, Open City so much that she wrote to Rossellini – adding that the only Italian words she knew were "Ti amo". Rossellini, Magnani's partner, kept the exchange secret, until she saw a telegram from Bergman. She lovingly plated some spaghetti, asking Rossellini if he would like some. When he replied yes, she answered: "Then eat it!" and threw it all at his face. This episode is recalled by friends and bystanders; the only detail that changes with the telling of the story is what pasta they were eating. In short, Magnani was intimidating. "Not cute, nor reassuring," says De Bernardinis.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Magnani was more brava, but Sophia Loren is the fantasy of the Italian woman. The icon, the dream," Vito Mancusi, professor of acting, tells the BBC, over dinner in Venice. When asked if he'd rather have a meal with Loren or Magnani, he replies: "Sophia, of course. She would sit here and gently savour these tiny clams. Meanwhile, Anna Magnani would be like: 'Where did you take me? What's this place? Is the food any good?' She was difficult."

More like this:

• The story behind Hollywood's most famous side-eye

• What makes Fellini the 'maestro' of Italian cinema?

• 16 of the best films of 2025 so far

Perhaps this is one reason why some women today admire Magnani. They like how she said that the camera shouldn't hide her wrinkles, because "it took her an entire life to make them". She made eyebags sexy. "She hated conventions, she was free, extremely free," says granddaughter Olivia. "The fact that she existed, without giving in to compromises, despite the photogenic standards of the time, despite a tormented biography, is important for a girl who chooses to do my job," Roman actress Liliana Fiorelli tells the BBC.

As important as Magnani was, It's hard to pin her down. Perhaps this is another reason why people might not know her as well outside her native country. "Italy has become a museum, but Magnani is alive," says De Bernardinis. "You can't grasp her, replicate her, or put her in a museum".

How should we remember her then? "Just watch her movies," says Olivia.

The 80th anniversary of Rome, Open City is in 2025.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebookand Instagram.