The hidden obstacles in the Scottish Budget

PA Media

PA MediaFinance Secretary Shona Robison's pre-election Budget has generated a range of headlines about quite minor changes.

There are proposals for income tax efficiencies, measures targeted at private jets, and higher council tax bills for those in pricey houses, mostly in Edinburgh.

But as the dust settles on the Holyrood rhetoric, what are we left with? A tight squeeze, and some hidden obstacles.

The Fraser of Allander economics institute says this was "the budget where the silences were loudest".

There wasn't much talk of 'fiscal drag', for instance, but it remains a feature of such budgets at Holyrood and at Westminster.

This happens when people find themselves paying more tax after being pushed into higher bands, even though the tax rate itself hasn't increased.

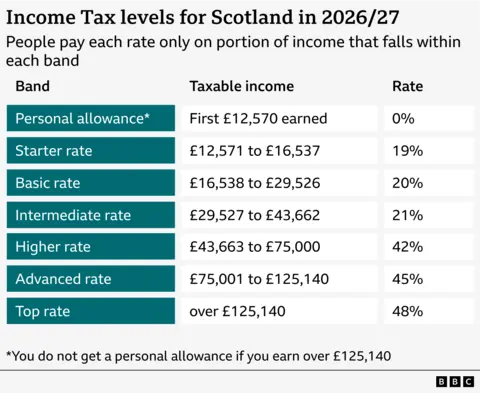

Shona Robison's plans would increase the threshold where people start paying basic and intermediate rates of tax from £15,398 and £27,492 to £16,537 and £29,527 respectively.

Aiming to ensure that more Scots pay less income tax than they would under Westminster's regime brings a saving of around £40 a year to lower income Scots, and £31.75 for above-average earners.

Not much, but nice to have, and why not let ministers make their political point?

But there is no change to the £43,663 figure where the higher rate kicks in, rising from 21p in the pound to 42p. The bands above that also remain frozen.

As a result, the £50m giveaway on lower thresholds compares with the £122m gained by the government on the higher rates, rising to a net gain of £200m after three years.

That comes from people on more than £43,633, who don't feel they are high earners.

When the higher threshold was set at just below its current level 10 years ago, some 304,000 Scots had income above that level.

By 2028, with that threshold frozen, the forecast is for 948,000. That's nearly 29% of taxpayers.

By freezing the threshold at a lower point than Westminster, the share of higher rate payers has shot up faster.

South of the Border, the ratio of higher rate payers is up from 15.3% to 22.9%.

What about the things that went unsaid on the spending side of the ledger?

Economists at the Fraser of Allander Institute point out that the day-to-day budget was down nearly half a billion pounds on expectations last summer, mainly due to undershoots in earnings and the income tax that comes from them.

Welfare choices

The position was helped by U-turns on welfare in Westminster, releasing more cash through the formula for its block grant to Holyrood.

But Holyrood's welfare choices are £1.1bn per year more generous than benefits would be under Westminster rules, much of that because of the Scottish Child Payment.

That benefits gap is smaller than previously forecast, according to the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC).

Not only has Rachel Reeves reversed her cuts at Westminster, but the approval rate of applications for Scotland's Adult Disability Payment have fallen sharply to just over one in three by last July, and are now below the equivalent benefit in the rest of the UK.

So things could be worse - but it's still very tight.

David Phillips, of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, points to a real terms rise in health and social care spending of only 0.7% next year.

He doubts that will last the year without more funding being raided from other budgets.

PA Media

PA MediaThe multi-year spending review published alongside the budget for 2026-27 shows a real terms cut in day-to-day spending the year after next, and three years of real terms cuts to capital budgets.

To plug the gaps, the Scottish government is borrowing within tight constraints and is dipping into its reserves and the windfall from wind farm leasing.

The SFC is unimpressed by use of one-off funds to plug recurring gaps. It's also warning about some of the assumptions about savings.

Over three years, Shona Robison wants to see £1.5bn in efficiencies, more than £1bn of that from health and social care.

The SFC cites Audit Scotland findings in raising a question mark over that target.

Only two of Scotland's regional health boards hit their efficiencies target last financial year, while seven required bailed out with loans. And loans are rarely repaid.

Some of these efficiencies come from cutting staff numbers, but ministers don't want that to affect the frontline.

The SFC questions how that scale of staff cut can be achieved with non-frontline staff, however they are defined.

SFC chair Prof Graeme Roy said: "It's OK to say that. The key is how you deliver it.

"We know that trying to make these efficiency savings is easier said than done."

Then there's pay. The figures assume public sector pay increases are within the pay policy, of 9% over three years.

But two years in, most of that has been taken up by deals, including those for doctors and other NHS staff.

It's calculated that health service workers would have to accept a pay rise of less than 1% in the third year of this pay policy.

And it's assumed by the SFC that's unrealistic and not going to happen. So something else has to give.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe spending area that is most often required to flex is local government.

Its representative, Cosla, says the allocation for next year falls short on all the asks that it had of Shona Robison.

On day-to-day spending, it's £1bn short, and on capital, it asked for £844m and got £681m.

That's true of most others lobbying the finance secretary for more money, including universities, colleges, prisons, pensioners and firefighters.

And there's "very real anger" from the licensed trade association that her support on business rates does not go much further.

Look beyond next year, and again, it's local councils that get walloped.

Health and social care get some growth between this year and 2028-29, of £1141m.

But to pay for that, local authorities take a real terms cut of £472m, or 2.1% per year.

The IFS calculates that would require an 8% council tax rise just to retain council spending power.

Big infrastructure projects

While Shona Robison has primed her budget to fit an imminent Holyrood election, her successor as finance secretary will have to face councillors as they go into elections next year.

Finally, what went unsaid on capital spending? The pipeline for big infrastructure projects has changed shape, in that projects have moved into a category of being unfunded, and without a timetable to completion.

So there's no schedule for upgrading the A96 between Inverness and Aberdeen - including a Nairn bypass - nor relief for those stuck in the most congested roundabouts on the outskirts of Edinburgh and Inverness.

In Argyll, there's no long-term solution to the Rest and Be Thankful road, frequently closed due to landslips, nor the precarious road along Loch Lomond-side north of Tarbet.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPorts at Ardrossan, Gourock and Mallaig await upgrade plans, and the Isle of Mull has been put on hold for new ferries.

Where Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Glasgow all have metro rail plans, the Scottish Government likes the ideas, but has no timetable for funds to support them.

New hospitals are required in Monklands, Fort William and Barra, but they are not scheduled or funded either.

And where the Scottish government had plans for NHS national treatment centres, some of which are open and operating, it has abandoned that plan in favour of a new approach.

It even has a name for said approach, with letters: the Whole System Infrastructure Plan, or WSIP.

The idea is that health boards are no longer to plan their own hospital and clinic needs, but such plans are to be co-ordinated centrally.

That's either a long overdue recognition of common sense, or the slippery slope to central government taking over the role of regional health boards.