An ancient route through the clouds

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsOnce part of the legendary Silk Road, Central Asia’s Pamir Mountains might be the world’s last true adventure.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsKnown in Persian as the “Bam-i-Dunya” (Roof of the World), Central Asia’s Pamir Mountains – located mainly in Gorno-Badakhshan, an autonomous region in eastern Tajikistan that borders China, Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan – are one of the highest ranges on the planet. Once part of the legendary Silk Road, the area was totally closed to foreigners during Soviet rule and has only recently opened up again to adventurous travellers.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsGorno-Badakhshan is connected to the outside world by the legendary Pamir Highway, which traverses the Pamir Mountains through Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. It’s the second highest paved road in the world (after Pakistan’s Karakoram Highway), with the highest point at Tajkistan’s Ak Baïtal Pass at 4,655m.

The Gorno-Badakhshan region can only be visited from May to September, as snow makes the road inaccessible during winter.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsReminders of the Pamirs’ significant position on one of the Silk Road’s southern branches can be seen throughout the region. The 3rd-century Yamchun Fort is one of the most impressive monuments in the Wakhan Valley, which runs along the Afghan border. Built on top of a cliff, it played a key role on the Silk Road by controlling traffic, cargo and security.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsA Tajik soldier stands on the ruins of the 4th-century Khakha Fortress in the Wakhan Valley, looking toward Afghanistan, which is just a few hundred metres away on the other side of the Panj river.

The border is heavily policed for security reasons, but every week, a cross-border market is held in the village of Ishkachim, bringing together traders and customers from the two countries under the watchful eyes of the military.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsSince the area is so isolated, the Pamiri people have a strong cultural identity that is markedly different from the rest of Tajikistan. The Pamiris are mostly Ismaili and thus belong to the Shia branch of Islam, while most Tajiks are Sunni Muslims. They also have their own languages as well handicrafts, jewellery and distinctive music and dancing traditions.

Every July, the capital town of Khorog hosts the Roof of the World Festival, where dancers and artisans from across the Pamir region – as well as other mountain communities along the historical Silk Road – come together. The festival has not only become a platform for cultural integration, but ensures the protection of the area’s unique heritage.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsIn Central Asian countries like Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan, the unibrow is considered a symbol of beauty and purity for women and of virility for men. If there is no natural unibrow, or if it is weak, women use a kohl liner or a modern kajal pen to paint it in.

This young girl from Ishkachim has travelled 100km north to Khorog for the musical festivities, resplendent in her village’s traditional dress.

Pascal Mannaerts

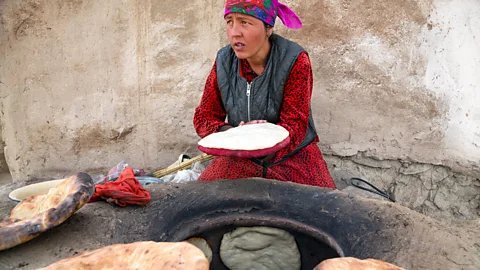

Pascal MannaertsDespite their colourful celebrations, livelihoods in the Pamirs are rudimentary. Economic activity here is mostly related to livestock herding and mining, and many Pamiris live a subsistence lifestyle.

Here, a young man tries to gather his herd of yaks to bring them back to the village of Bulunkul for the night. Yaks, as well as other animals like goats and sheep, are vital to the villagers’ survival, providing them with meat to both eat and sell. There are no other job opportunities out here.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsIn Bulunkul, 20 families live in basic houses made of clay bricks, mud, wood and stones. There are no paved streets; the nearest road is the Pamir Highway, 16km away.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsIn Bulunkul, we only have one little shop in a house, selling things like oil, rice and little chocolate bars. Once every 15 days maybe, a truck comes here from Khorog, supplying us with staples – Zainab, a Bulunkul resident.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsAbout 50 children attend the village’s single school, which has just two teachers. When they leave, around age 18, some will remain in the village to care for their families and their flocks. Others, mostly men, will head to Khorog or elsewhere in Tajikistan – or move to Russia to look for work. However, the Pamiri people are resilient and many prefer to stay.

Pascal Mannaerts

Pascal MannaertsHere in Bulunkul, we are used to this kind of living. We have our cattle, our homes, our children. What do we need more? Our life is here. I have been to Khorog many times but I would never wish to live in a city. We are happy here. – Sakina, a Bulunkul resident