Burnt at the stake for an idea 'just months ahead of its time'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was a sight few people would question nowadays: a young woman sitting alone in Lincoln Cathedral reading from the Bible. But during the reign of King Henry VIII, this simple act ended with her being burnt at the stake.

Anne Askew was just 25 when she became one of the final victims of the religious turmoil under Henry, who died six months after her.

So how did her faith, and her refusal to hide it, clash with the king's beliefs, putting her on trial for her life?

Local historian Adrian Gray has been delving into Anne's story for the BBC's Secret Lincolnshire podcast.

"If you believe that you have the purest truth you can possibly get, and that truth will give you eternal life, will you compromise because somebody tries to bully you?" he asks.

"A lot of people would, but she didn't."

On the surface, Anne might look like an unlikely rebel. She was born into the Lincolnshire gentry in the village of South Kelsey in 1521, the daughter of an important landowner.

As was often the way at the time, a marriage was arranged for her as a teenager.

But she grew up at a time when Henry was in the process of breaking from the authority of the pope and establishing the Church of England – a period now known as the Reformation.

Her brother, Edward, worked for Thomas Cranmer, a key figure in the church who became Archbishop of Canterbury, and Anne became interested in the new ideas about religion.

"She educated herself by reading the Bible," Adrian says.

"Many people at the time considered that women would find it very difficult to engage with intellectual ideas and it would disturb them."

Anne decided to challenge that perception in Lincoln Cathedral.

"She went there with a Bible and sat and read it in the cathedral for nine days.

"Her friends told her that she'd get into trouble, but she went anyway.

"They certainly were hesitant about women reading the Bible.

"But her view was very different. All the priests in the cathedral hesitatingly tiptoed around her, not brave enough to take her on and challenge her.

"Here we've got this woman, very confident, somewhat aggressive in her approach to life and not scared of anybody."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter this show of intent, Anne, who had cut ties with her husband, decided to leave Lincolnshire for London.

By the late 1530s, however, Henry had started to regret some of his earlier reforms.

He held on to many of the old Catholic beliefs – and questioning them was dangerous.

In 1539, the law of the Six Articles set out what people should believe – and those who disagreed could be accused of heresy.

"Catholics always believed that when the priest blessed the bread at the communion, it physically became the body of Christ," Adrian explains.

"But Protestants, more widely, were doubting and challenging it, saying Jesus just meant it as a symbol."

This is when Anne got into trouble. She was known for preaching in the streets, but she also preached to others privately, including groups of women. It led to her arrest.

She was taken to be interrogated by the authorities in London – powerful men who expected her to give up and back down. But instead, Anne faced them head on.

"The lord mayor was a bit upset by her answers and challenged why she wasn't answering properly, to which she replied, 'I will not cast my pearls before swine, acorns be good enough'," Adrian says.

Her answer paraphrases a section of the Sermon on the Mount, as recounted in the Gospel of Matthew.

"She certainly knew her Bible very well and was not going to take fools gladly."

Although she was eventually released and returned to Lincolnshire, Anne was later brought in to be questioned again.

"She was still in trouble. She hadn't repented of her opinions," Adrian says. "Do you think she was afraid? Not a bit of it. She absolutely stuck to her beliefs."

For Anne, it all came down to one question: does the bread become the body of Christ once the priest has blessed it?

"And her response to that was, let's lock it in the cupboard for a few months and see what it's like after that. Will it still be the body of Christ? No, it will remain bread."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn June 1546, she was convicted of heresy and condemned to death.

Anne was moved to the Tower of London, where she was tortured on the rack – a shocking and illegal act, given she was of noble birth and awaiting a death sentence.

But her opponents knew Anne was "an entry point" into a network of people who had similar radical Protestant opinions.

They would have included Henry's sixth and last wife, Catherine Parr, a prominent progressive Protestant.

But Anne refused to give evidence the opponents of the queen were looking for.

When taken out to be burnt alive at Smithfield, on 16 July 1546, she is said to have faced her fate bravely.

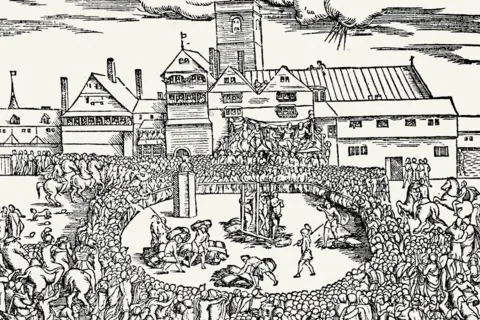

"They would have piled up faggots of wood in advance," Adrian explains. "There was a ring actually fenced round where people could gather to watch

"It would have been a big deal because she was quite famous, quite notorious."

It is hard to imagine the courage Anne showed in sticking to her beliefs. Today, she is remembered in Protestant churches across England, including Lincoln Cathedral.

Following Henry's death, the Church changed its stance on the communion bread.

"It's particularly tragic, because she was burnt for an opinion that was only a few months in advance of its time," Adrian says.

"But that was a time when your opinion and your belief could get you burnt at the stake."

Listen to highlights fromLincolnshire on BBC Sounds, watch thelatest episode of Look Northor tell us about a story you think we should be covering here.

Download the BBC News app from the App Storefor iPhone and iPad orGoogle Play for Android devices