'The American way of life is about to change': How the 1973 oil crisis forced Nixon to rethink time

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen an oil embargo rocked the US, the president's radical solution was to make citizens start their working days an hour earlier – even in the darkness of midwinter.

"Spring forward, fall back" can be a useful way for Americans to memorise the seasonal ritual of clock changes, but in January 1974 the US government spoiled this nifty wordplay by introducing year-round daylight saving time in the middle of winter. The idea was that clocks would go forward by an hour, two months earlier than usual, even though that meant that the working day would begin while it was still dark. The new mnemonic would have had to be something like "Winter forward, fall… errr… stay where you are", which is nowhere near as catchy.

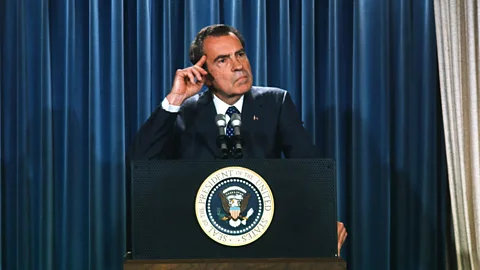

President Richard Nixon announced the experiment in a televised address in November 1973 as part of an emergency response to deal with an oil supply crisis. The move was meant to conserve fuel by reducing electricity demand in brighter evenings, but, in the mornings, it left children waiting for school buses in pitch black and commuters facing rush hour before daybreak. Reporting on Nixon's various measures, the BBC's US correspondent John Humphrys noted, "The American way of life is about to change."

Since the 1950s, the West's prosperity had relied on a steady flow of cheap oil. That changed in October 1973 when oil-exporting nations turned energy into a weapon during the Arab-Israeli War. Prices were raised sharply and an embargo was imposed to put pressure on Israel's allies, most notably the US. Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani, Saudi minister of petroleum, told the BBC's Panorama: "The era of a very cheap source of energy is done, and this is a new era."

In his BBC News report, Humphrys observed: "Americans have refused to take the fuel crisis seriously in the past, but Mr Nixon's broadcast left them no choice. The measures he outlined will affect the country in all sorts of ways. Motorists will have to drive more slowly. The speed limit, which varies from state to state, will be lowered to 50mph. And Mr Nixon appealed to people to use carpools to get to work." Fuel supply to airlines was reduced, with 10% of all services cancelled. With industry turning towards coal, Humphrys said that it would be "sacrificing many of the anti-pollution measures, so Americans can expect the air to grow dirtier".

The president even urged Americans to lower their thermostats in homes, offices and factories by at least six degrees Fahrenheit. Anticipating a chilly response, Nixon tried to thaw the tension. "Incidentally, my doctor tells me that in a temperature of 66 to 68 degrees (18C to 20C), you're really more healthy than when it's 75 to 78 (23C to 26C), if that's any comfort," he said.

A month later, while signing year-long daylight saving into law, Nixon said that other measures required "inconvenience and sacrifice". In contrast, he said that changing the time would "result in the conservation during the winter months of an estimated equivalent of 150,000 barrels of oil a day, will mean only a minimum of inconvenience and will involve equal participation by all".

Prices at US fuel pumps rose 50% over the winter months. In his 2009 BBC radio series America: Empire of Liberty, Prof David Reynolds said: "Admittedly, at around 60 cents a gallon, the cost was hardly crippling by today's standards. But to a country that assumed that cheap gas was an American birthright, the oil crisis was a real shock." Reynolds noted that an opinion poll in December had detected signs of panic, with people said to be fearful that the country had run out of energy. "This was nonsense, of course," he said. Still, while domestic production satisfied two-thirds of US needs, the other third came mostly from the Middle East, and "the price hike plus public panic created a crisis".

The second dark age

Even before the shock of the oil crisis, the US had already been experiencing fuel shortages. Humphrys reported in May 1973 that "petrol in the most fuel-hungry country in the world is in short supply". For added colour, the report contained part of an advertisement for the former US oil giant Amoco presented by Johnny Cash, who said: "It's hard to believe that this great country of ours has an energy crisis, but it does." The country star urged motorists to slow down to save on petrol. "You'll get there, and there'll be more gasoline for everyone," he promised. In another Amoco advert, he talked of "a new pioneer spirit in America today, the spirit of conservation".

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Sign up to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

Cash's message of dialling down six degrees at home and slowing down on the highway was echoed by Nixon. What was not part of the Man in Black's advertising sermon was year-round daylight saving time, a measure sure to be unpopular with many among his heartland audience. While time zones are a human invention, cows don't know what time it is, so that extra hour of winter darkness in the morning was an extra challenge for farmers.

While Nixon was knee-deep in the Watergate scandal at the time, he might have learned from the UK's experience a few years before, when the clocks were put forward as usual in spring 1968, and then not put back until autumn 1971. The lasting image was of children in fluorescent armbands trudging to school through the gloom. While some businesses involved in trading with continental Europe appreciated being in the same time zone, the measure was not welcomed by those who had to work outdoors. It was least popular in the far north of Scotland, where some people had to wait until 09:45 for their first glimpse of winter sun.

More like this:

• How a 2003 blackout brought New York to a standstill

• How the US dropped nuclear bombs on Spain in 1966

• The fatal accident that haunted Ted Kennedy's life

Daylight saving time itself was first brought in during World War One by Germany and Austria, and other countries followed suit. The aim was to maximise daylight hours in order to conserve precious coal supplies. It was introduced by the US in 1918 but it was so unpopular when the war ended that the legislation only lasted seven months before being repealed.

The US 1974 iteration of year-round daylight saving time did not last much longer than its first wartime experiment. When it was introduced on 6 January, the New York Times quickly dubbed it "the second dark age". Opposition was focused on dark winter mornings and doubts about the promised energy savings. The Hartford Courant newspaper reported that a day after it took effect, four Connecticut teenagers were struck by cars on their way to school. A survey in December 1973 suggested that 79% of those interviewed were in favour. By February 1974, that figure had dropped to 42%. In the end, the measure outlasted Nixon's presidency only by a few weeks, with his successor Gerald Ford signing a law to repeal it in October.

As for the oil crisis, it passed but its effects were felt for years. According to David Reynolds in 2009, one lasting legacy was what economists called stagflation, a combination of stagnant growth and soaring inflation that endured for the rest of the decade. "The US coped better than most developed countries, but 8% inflation and 7% unemployment were undoubtedly shocks to the system after the long post-war boom," he said. It also led Europe and the US to begin cultivating different oil suppliers, as well as thinking about alternative energy and fuel efficiency. The end was nigh for the heavy gas-guzzling car.

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to theIn History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebookand Instagram.