Easy money? No, this scam can wreck your credit – and your life

Getty Images/BBC

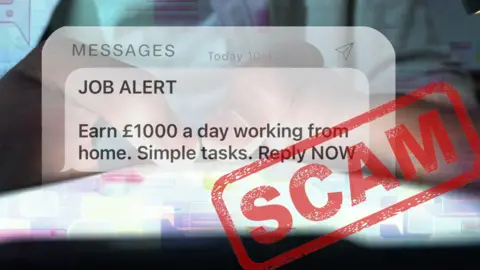

Getty Images/BBCWhat would you think if you got a text offering £1,000 a day for just 90 minutes of work – from home?

It sounds too good to be true. And of course, it is.

Experts say this sort of text is almost certainly looking to hook in a victim for money laundering - where people are asked to move money through their bank account by criminals and, in some cases, keeping an amount back for themselves.

In doing so the person could have committed fraud.

Statistics from the Financial Conduct Authority show there were at least 207,889 cases of "money muling" in 2024, with the majority of those involved aged under 30.

Criminals use job adverts via texts, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Facebook, as well as chatting to people online and even in person, to find their victims – and are wrecking lives in the process.

That is something Molly - which is not her real name - knows all about.

"To the outsider, it probably seems obvious that you are getting scammed, but when you are in that moment and you are trusting this person, they become your lifeline," she said.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, she told the BBC that she wanted to warn others about the risks, having lost her own job, her bank account and her chances of being able to buy a home.

Molly says she was coerced into becoming a money mule in 2023 when she started speaking online with a man who promised to teach her about crypto trading.

After about a year, he said he would deposit £2,100 into her account, which he claimed had come from crypto trading, and she could keep £300 of it if she withdrew the rest.

His explanation was that he had no bank card so was not able to withdraw the money himself.

"I was busy with work and I didn't want to do it," Molly said. But he ignored her refusal and made the transfer anyway.

He then got her to make a payment of £900 to someone else's account, and to withdraw a second £900 in cash.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I was unsure of the situation," she said.

"I was intimidated. You're just thinking, 'What the hell's going on and how do I get out of this?' I just wanted to get out of this situation and just literally go back to my job."

Lloyds bank then froze her account permanently.

A marker was also placed against her name on the National Fraud Database, which is run by Cifas, a fraud prevention organisation.

The marker meant she could not get a mortgage or any other form of credit, scuppering her plans to buy a house. And, when her employer in financial services found out about the marker, she was sacked.

All of this happened without any court proceedings.

"I'm definitely angry," she said. "But it's more like a slow inner rage now. I just think it's opened my eyes to the system. [In] the criminal system you go to court and it's innocent until proven guilty, whereas the banking system is guilty until proven innocent."

After being contacted by the BBC, Lloyds said they would be removing the fraud marker. It had been in place for more than a year.

In a statement, Lloyds said: "We understand people can be manipulated or coerced by scammers, which can be very difficult to spot.

"No legitimate company or investment will ask you to use your bank account to transfer their money."

Many others are in a similar situation. The Financial Conduct Authority has told the BBC it reported 207,889 cases of money muling in 2024, a rise of 22% compared to the previous year.

Under-30s made up 61% of cases reported to the National Fraud Database, run by CIFAS.

Devon lawyer Jeremy Asher, who specialises in fraud marker removals, said: "We're seeing vast numbers of people being hooked into believing they're being employed by businesses through social media.

"They believe they're being paid to do a legitimate job and they're being paid to move money for people."

In fact, they are helping criminals to "cash out their ill-gotten gains", said Asher.

"[Criminals] in effect recruit armies of individuals who will move that money for them," he said.

"The money is in effect split down into smaller denominations and moved through different accounts and then out either into cash or into realisable assets like property or cryptocurrencies or moved abroad."

The more bank accounts that the money passes through, the more difficult it is for authorities to trace its origin.

'Students at risk'

All of the major High Street banks are members of Cifas, enabling them to place names on the National Fraud Database.

The markers can last for up to six years.

Asher said he has been contacted by "thousands" of people asking about the markers.

It is possible to challenge them – and sometimes to get them removed, but the process is slow and difficult, he said.

In a statement, Cifas said cases recorded on its database "must meet strict standards of fairness, lawfulness, transparency, and accuracy".

Cifas said these principles include a "defined standard of proof, ensuring decisions are based on credible evidence".

Asher is now hoping to "reverse the disease of money muling" by delivering training in schools and universities through his Financial Fraud Awareness Campaign.

Dr Sam Mapston, a senior law lecturer at the University of the West of England in Bristol, has warned students about the practice in her "Dangers of Money Muling" sessions.

She tells them that, should they agree to be a money mule in the knowledge that the proceeds are illicit, they can be prosecuted for a money laundering offence.

That is not to mention the knock-on effects of being blocked by banks – including difficulty getting a student loan or a phone contract, or losing access to certain professions such as law and accountancy.

"I think students are particularly at risk because they're at a time in their lives where they perhaps have financial pressures," she said.

"It's expensive to study at university and they're not earning lots of money... and so [criminals] are targeting students."

UWE student Charlie Brennan, who attended the session, told the BBC he had been offered a money mule deal – but refused.

"They [criminals] come up to younger kids," he said.

"They're like... We'll send you 200 quid. You can keep £10 if you take out 200 quid and give me the cash.

"That sounds like a sick deal for a 14-year-old. But it is too good to be true."

Another of Mapston's students told her she had been targeted via a WhatsApp message – and, desperate for money, had replied.

Mapston said that, luckily, she had not yet handed over her bank details.

The student, she said, was able to block the number – and firmly shut what might have been the door to a world of trouble.

A Financial Conduct Authority spokesperson said: "Social media companies need to step up. It's largely through their platforms that people are recruited as mules.

"It's important banks and building societies play their part too, including closing accounts they have suspicions about. Only a small fraction of accounts are closed – and we expect firms to act proportionately and treat customers fairly."

Reflecting on the experience Molly said it had opened her eyes to the way scammers operate and how the banking system worked.

"I'm definitely not the same person I was," she said.

If you want to contact us regarding this story, email [email protected]

Follow BBC West on Facebook, X, and Instagram. Send your story ideas via WhatsApp on 0800 313 4630.