Under the radar: The pilot who posed as a farmhand to evade the Nazis

IWM Duxford

IWM DuxfordA farm labourer is toiling silently in the fields of northern France in the summer of 1944.

It is just weeks after D-Day and all around him are German soldiers, using the farm in Normandy as their base.

They don't know that the man in the blue shirt is not the deaf and non-speaking migrant worker he claims to be.

He is actually an American fighter pilot who has bailed out of his stricken plane and is hiding in plain sight.

The young airman from Utah will need to stay in character for nearly two months if he is to evade capture.

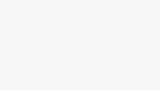

Now the forged identity documents supplied to 2nd Lt Lonnie Moseley by the French Resistance, along with other personal effects - including his diary and parachute ripcord - are going on display at his former base.

They are being showcased in one of three new interactive exhibition spaces at the Imperial War Museum (IWM) Duxford, in Cambridgeshire, opening on 5 December and telling the stories of the Allied pilots who served there.

IWM Duxford

IWM DuxfordThe 23-year-old pilot had been flying only his second mission with the US Army Air Forces' 78th Fighter Group.

He was flying over occupied France when his plane's engine "stopped on him several times" before cutting out entirely, says his son Richard, 69.

"When his P-47 Thunderbolt went into a wild spin, he feared he would get caught in the shrouds of his parachute as he knew that would kill him.

"He didn't open his parachute until he was nearly at treetop level and felt the smack of the parachute and an impact on the ground almost simultaneously.

"He always said it was a hell of a way to spend 4 July [US Independence Day]."

IWM Duxford

IWM Duxford IWM Duxford

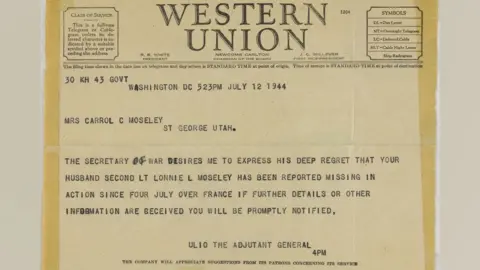

IWM Duxford2nd Lt Moseley was travelling at about 150mph (240km/h) when he bailed out of his aircraft at roughly 5,000ft (1,500m).

Moments later, it crashed near Hauville, about 40 miles (64km) east of the D-Day beachhead.

He believed he was briefly knocked out and when he opened his eyes, farmer Lucien Lestang was standing close by.

Neither spoke the other's language and the first thing the farmer needed to determine was whether the pilot was German or an Allied liberator, while the pilot hoped Mr Lestang was not a Nazi collaborator who would hand him in.

Initially, they communicated using some French/English phrases supplied as part of the pilot's escape kit, but later a schoolboy who spoke some English was able to translate.

IWM Duxford

IWM DuxfordDressed as a labourer in clothes supplied by the Lestang family, he hid in woods for a few nights, evading German soldiers searching for Canadian airmen from another downed plane.

"My father told dozens of stories about his time in France - about being hidden in a barn; when he had the opportunity to sit at a meal with a German officer; how he picked up razor blades discarded by German soldiers so he could shave," says Mr Moseley, a retired fire marshal from Salt Lake City.

"The forged ID papers said he was a deaf migrant worker, unable to speak, and came from across the line controlled by the British, so the Germans couldn't verify them."

Once he had those papers, he was able to leave the barn and help with farm work.

But first, he taught himself not to react to the sound of the Lestangs' chiming clock, so as not to give himself away.

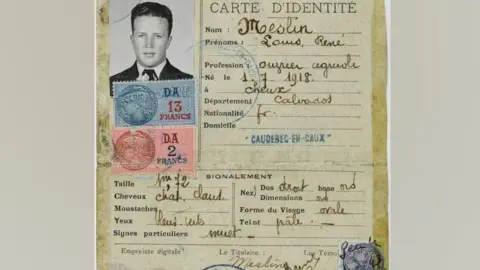

Back in Utah, his 21-year-old wife Carol received a telegram, saying he was missing in action.

She had already lost a pilot brother, shot down fighting the Japanese in the Pacific.

IWM Duxford

IWM Duxford2nd Lt Moseley assumed the name Louis René Meslin and, over the following weeks, got to know Papa and Mama, as he called the farmer and his wife Nelly, and their children, Bernard and Lucienne.

As Lucienne was just 10, she was not told his true identity, in case she inadvertently gave him away.

On one occasion, Mr Moseley says, his father went shopping with the family but refused to show his papers to a German soldier - until he cocked his machine gun.

By sheltering him, the couple were risking their lives. The Germans had announced that anyone found helping downed airmen would be shot.

When the airman heard the Allies were closing in on Hauville, he decided to go to meet them, against the wishes of his hosts.

IWM Duxford

IWM Duxford IWM Duxford

IWM DuxfordHe soon encountered British forces, believed to be from the 7th Armoured Division, the "Desert Rats".

Wary of German spies and deserters, it took them two days to confirm he was a missing US pilot, and he was transported back to Duxford on 30 August.

Only then did Lucienne learn he was not only American but could speak. "She was totally shocked," says Mr Moseley.

The airman's comrades were equally surprised when he arrived back at Duxford.

"The tradition was to leave a missing man's bunk empty until he was confirmed dead or captured, and when his crew mates found him sitting in his escape clothes on his bunk, they were furious about this civilian desecrating his bed - and then thought they'd seen a ghost."

The policy was not to send evaders back to the same theatre of war, so 2nd Lt Moseley was returned to the United States following his debriefings.

IWM Duxford

IWM Duxford Richard Moseley

Richard MoseleyThe airman and his wife went on to have three sons, and he spent 33 years serving in the US forces.

The family continues their friendship with the Lestangs to this day.

When his father died aged 93 in 2014, Mr Moseley decided to visit Duxford.

This inspired him to donate his father's archive to the museum, with his family's agreement.

"We have some wonderful museums in the United States, but that's not where the story belongs - it belongs to Duxford," says Mr Moseley.

Emma Baugh/BBC

Emma Baugh/BBCThe archive is incredibly detailed, as "if the pilot had the foresight [the items] would be in a museum one day", says IWM senior curator Adrian Kerrison.

Other exhibits include the clothes the airman wore while on the run, the missing-in-action telegram sent to his wife and various photographs, including one showing him and the farmer posing by the wreckage of his downed plane.

"I am so happy that it is finally going on display for our visitors to see, and in one of the hangars that Lonnie himself would have frequented over 80 years ago," says Mr Kerrison.

"It's just an incredible story of bravery, perseverance and just trusting humanity. The relationship that he built with the French family really speaks to that, and that relationship they built up lasted until he died."

Emma Baugh/BBC

Emma Baugh/BBCFollow Cambridgeshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.