The festive traditions with roots in London

Rischgitz/Getty Images

Rischgitz/Getty ImagesChristmas is never a time short of a few traditions - whether arguing about politics while eating dry turkey or leaving mince pies and a beverage for Father Christmas.

And some of the customs we wheel out every year have their hearts in the capital.

We've all heard the Germans were behind the popularity of the Christmas tree - but the tradition in the UK at least, stems from London.

Queen Victoria (born to a German mother) and Prince Albert (likewise, and also father) became the Christmas tree's champions - but it was Victoria's grandmother, Queen Charlotte (also German) who was believed to be the first to stick a decorated yew branch in a tub and take it indoors.

More directly homegrown, crackers, lights and cards all originated in the city.

Christmas cards

Hulton Archive via Getty Images

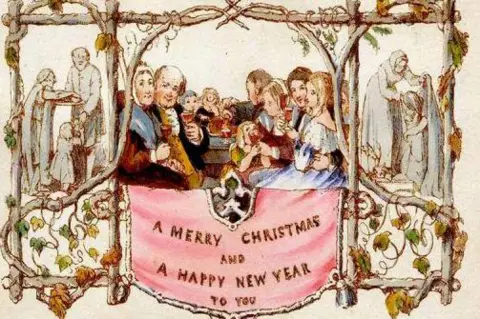

Hulton Archive via Getty ImagesSir Henry Cole of London came up with the first Christmas card in 1843 by commissioning his friend, the artist John Calcott Horsley, to design a holiday card that would replace his seasonal task of writing many letters.

Horsley depicted a Victorian family - all quaffing what seems to be red wine - flanked by images of poor people being given gifts of food and clothes, all framed with twisted branches of wood and ivy.

A Merry Christmas And A Happy New Year To You was added to the front, and there were spaces for the names of the sender and recipient.

Published by Joseph Cundall from his premises at 12 Old Bond Street, a run of 1,000 was printed by Jobbins of Warwick Court in Holborn.

The idea of the card proved popular, but it was not immediately reprinted - partly due to criticism by the Temperance League which disapproved of the family's dinnertime drink, and also because at a shilling apiece they were fairly pricey.

It would have been worth the investment though.

About 15 remain - and according to Guinness World Records, are the most valuable Christmas cards in the world - one was sold at auction in Wiltshire on 24 November 2001 for £20,000 ($28,158).

Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Hulton Archive via Getty ImagesCrackers

Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Hulton Archive via Getty ImagesThe Christmas cracker was invented by London confectioner and baker Tom Smith who had a shop in Goswell Road, Clerkenwell, in the 1840s.

He initially produced wedding cakes and sweets - until, on a trip to Paris he discovered the French bonbon, a sugared almond wrapped in a twist of paper.

Bonbons proved a hit at Christmas time and to encourage year-round sales, Smith added a small love motto inside the wrapper.

The inspiration to add the explosive "pop" was supposedly sparked by the crackling sound of a log fire.

Smith patented his first cracker device in 1847 and perfected the mechanism in the 1860s.

It used two narrow strips of paper layered together, with silver fulminate painted on one side and an abrasive surface on the other - when pulled, friction created a small explosion.

To stave off competition, the company introduced a range of cracker designs, which were marketed as a novelty for use at a wide range of celebrations.

Tom's son, Walter, added the elaborate hats, made of fancy paper, and sourced novelties and gifts from Europe, America and Japan.

The success of the cracker enabled the business to grow and move to larger premises in Finsbury Square, employing 2,000 people by the 1890s.

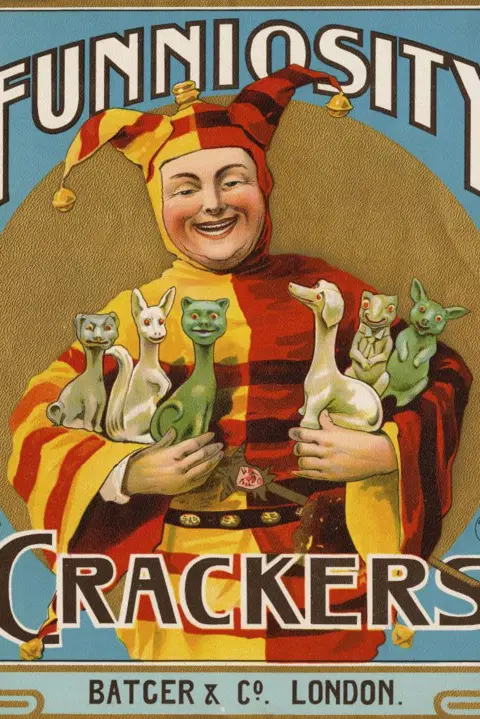

Batger and Company via V&A

Batger and Company via V&ACrackers and their hats were made by hand, which involved cutting tissue paper with heavy guillotines, pasting, folding and carefully packing.

Topical trends were followed - writers composed snappy lines, and the artwork for cracker boxes referenced crazes, from jazz to Tutankhamun, motorcars, Charlie Chaplin and the wireless.

The cracker boxes were collected and traded in their own right, with Batger and Company, an 18th-Century sugar refiner which had branched into confectionery and novelties following Smith's success, becoming well known for its cracker labels.

Archive Photos/Getty Images

Archive Photos/Getty ImagesWorld War Two caused paper rationing and a restriction on the manufacture of cracker snaps, but the industry recovered.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Tom Smith & Co was making 30,000 a week.

The Tom Smith brand still makes luxury crackers, including special crackers for the Royal Household, although the designs and contents are a secret.

(Unfounded speculation has it that Princess Anne likes a small hat with a tartan print that won't interfere with her one day off a year, King Charles has a massive crown to fit on top of his actual crown and Prince Edward has one that his wife picked out.)

Museum of London

Museum of LondonLights

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Christmas lights were first switched on in central London, they were such a great attraction they inspired an (unsuccessful) attempt in the House of Lords to bring action against those responsible for causing chaos and obstruction.

Regent Street was first lit up in 1954. Prompted by an article in the Daily Telegraph commenting on how drab London looked at Christmas, the retailers and businesses which made up the Regent Street Association organised and financed the first display.

Oxford Street followed suit in 1959.

The lights went out in Oxford Street in 1967 as the economic woes of the late 1960s hit, and four years later Regent Street also succumbed.

But in 1979 normal practices resumed and since then funding has always been a contentious issue.

As cities grew and public celebrations became more common, Christmas lights moved beyond private homes and became less about lighting a single tree and more about communicating celebration.

Light was used to catch attention, guide people through spaces and signal that a shared holiday experience was taking place.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTrees

Joseph Nash via Getty

Joseph Nash via GettyIn 1761, Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Streilitz became wife to King George III.

She brought German traditions and interests to the English court, including music, botany, and, presumably, ruthless efficiency.

In 1800, she held a large Christmas party for the children of all the principal families in Windsor, deciding that instead of the customary yew bough, she would put up an entire tree, cover it with baubles and fruit, and stand it in the middle of the drawing-room floor at Queen's Lodge.

One of the men in attendance, Dr John Watkins, wrote of the occasion: "Here, among other amusing objects for the gratification of the juvenile visitors, in the middle of the room stood an immense tub with a yew tree placed in it, from the branches of which hung bunches of sweetmeats, almonds and raisins in papers, fruits and toys most tastefully arranged and the whole illuminated by small wax candles."

It was a roaring success, and the queen would continue to stand up trees at royal residences. The tradition carried on after her death.

By 1840, the popularity of and fascination with the now-Queen Victoria and her husband led to fans copying the details of their lives.

When Albert ordered fir trees from his native Germany be delivered to the court as Christmas trees, the English public began to mimic the practice, placing trees in their own homes.

And we still do.

Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Hulton Archive via Getty ImagesListen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk