I inhaled traffic fumes to find out where air pollution goes in my body

BBC

BBCI feel contaminated.

I'm in a laboratory staring at my blood under a microscope. Rather than pristine red blood cells, some of them have been tainted with black markings. I'm now one of the first people in the world to see air pollution building up inside their body.

Less than an hour ago I was standing next to four lanes of busy central London traffic. It was the type of road where you can taste the air and you're left with a gritty sensation in your mouth.

I had volunteered to stand there for 10 minutes; breathing in dirty air as part of an experiment to understand how air pollution is affecting our bodies and damaging our health.

In the UK, poor air quality is thought to kill 30,000 people a year, as well as harming babies in the womb and exacerbating conditions from asthma to dementia.

Most of the air pollution I was breathing in came from traffic – billowing invisibly out of exhaust pipes, but also released by the wear and tear of tyres and brakes.

Prof Jonathan Grigg, from Queen Mary University of London, calls this spot his "exposure chamber".

Shouting over the blare of revving engines and sirens, he tells me most people incorrectly assume air pollution is all filtered out by our nose or mouth, or is trapped and then brought up out of the lungs.

"What we're looking at is whether the smallest particles are not only staying in your lung, but moving across into your bloodstream and going around your body," says Grigg.

Tom Bonnett

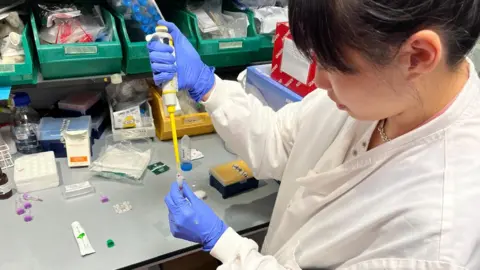

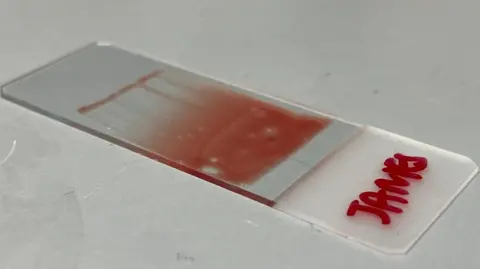

Tom BonnettAfter our dose of London air, we head back to the laboratory where I have my finger pricked and a sample of blood prepared for examination.

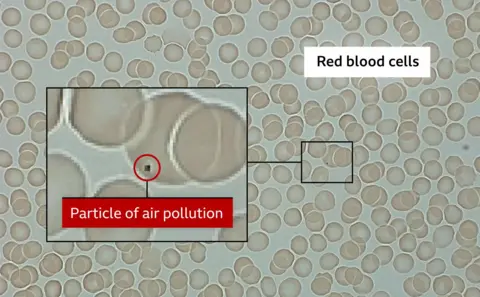

Under the microscope, we can easily see the red disc-shaped cells that transport oxygen around our bodies.

It takes a few minutes for me to get my eyes in, but then the air pollution becomes apparent. It appears as tiny black dots stuck to the red blood cells.

These are pieces of carbon and other chemicals, like a miniature lump of coal, that come from the incomplete burning of fuel. They're known as PM 2.5, because the particles are smaller than 2.5 micrometres.

I'm not surprised to see air pollution, it's why we're doing the experiment, but I can't escape a feeling of being dirtied, contaminated… sullied by it.

Tom Bonnett

Tom Bonnett Tom Bonnett

Tom Bonnett Tom Bonnett

Tom BonnettResearcher Dr Norrice Liu has looked at more than a dozen volunteers' blood samples as part of a study.

On average, one in every two to three thousand red blood cells had picked up a hitch-hiking piece of pollution.

That might not sound like much, but scale it up to the full five litres of blood in an adult and the researchers estimate there could be 80 million red blood cells transporting pollution around our bodies.

"It's a bit upsetting to see that, isn't it?" says Liu. "Every time I walk by a busy road, now I'm thinking how much of this is travelling around my body… you just feel like you don't want to be out on the road much."

I stood beside the road for just 10 minutes. It was busy, but it was not an extreme scenario. Your blood has probably looked like this too.

The team at Queen Mary University of London have shown that levels of air pollution in the blood come back down after about two hours of breathing clean air.

Grigg was "pretty shocked" the air pollution was so visible in blood, but says the important question is where it's going.

It's not being breathed back out, he says, some may be filtered out by the kidneys and leave the body in urine. But the most likely answer is that particles of pollution are "wiggling their way through the lining of the blood vessels and lodging in various organs".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis research is starting to explain why air pollution has been linked to so many health problems far beyond the lungs, including in the brain and for babies still in the womb.

Deposits of black carbon from air pollution have been found in the human body including in placentas analysed after birth.

"There's no reason why it's choosing one organ over another," says Liu, "so chances are they're everywhere."

And there are other forms of air pollution, such as nitrogen oxides, which are gases and are not visible down the microscope, but are known to cause harm.

The World Health Organization says 99% of the world population breathes in polluted air leading to seven million deaths a year. A report by the Royal College of Physicians estimates the figure for the UK is 30,000 deaths a year.

Sir Stephen Holgate, who led that report, said there was no doubt air pollution was damaging our health - "it's nailed, it's game set and match" - and the clearest evidence was coming from areas that were cutting air pollution and seeing the benefit.

But now that air pollution is "largely invisible", unlike the smogs of yesteryear, most of us don't realise we're breathing it in and "don't really understand that air pollution on a daily basis is damaging", he says.

Air pollution has been linked to harms throughout our lives and throughout our bodies.

There are many ways dirty air can harm the other organs of our body, but triggering inflammation is thought to be the main one. Inflammation is our body's natural response to injury and infection, but can also affect blood vessels to make heart attacks and strokes more likely.

Inflammation in the lungs has been shown to wake up dormant cancerous cells, which then develop into deadly tumours. Around one in 10 lung cancers are thought to be caused by air pollution in the UK.

Even while in the womb, air pollution is even thought to alter how a developing baby's DNA is functioning during critical stages of development.

"There's a very sensitive period when air pollution can cause a problem and it undoubtedly does: small lungs, small heart and some problems with brain development," says Sir Stephen.

At the other end of life, components of air pollution seem to be "accelerating the process" of dementia, he says, by helping plaques of toxic proteins form inside the brain.

What can you do about it?

There is advice on how to minimise our exposure to air pollution - including walking on quieter side streets or keeping away from the edge of the road so you're further from traffic. This is especially important for babies in buggies, who are much closer to the height of exhaust pipes.

Grigg's study showed a tight-fitting FFP2 mask led to less air pollution in the blood, but "we're not saying that everyone should wear a mask", says Grigg, adding some clinically vulnerable people including those "recovering from a heart attack or have chronic respiratory disease" might benefit while in areas of high pollution.

But the tricky thing with air pollution is you're often breathing in the pollution caused by other people. It is not easy to just live somewhere else if your house is on a busy road.

Changes to cars – not just sales of electric vehicles, but emissions standards on newer diesel and petrol engines – are improving air quality.

But Grigg says: "I think the more we understand the mechanisms of how it can cause these effects, the more we can add to the pressure for policy makers to reduce exposure - because that's the answer in the end."

Inside Health was produced by Tom Bonnett