X-51 Waverider: Hypersonic jet ambitions fall short

US Air Force

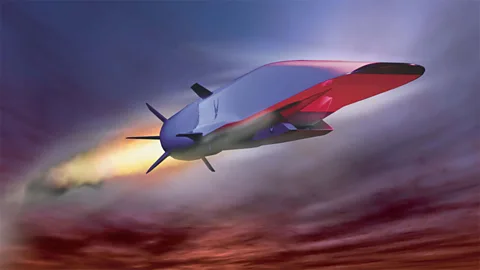

US Air ForceThe dreams of being able to fly from New York to London in under an hour are once again put on hold, as the latest effort to fly at over five times the speed of sound ends in failure.

When Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in 1947, it ushered in a new era of high-speed air travel. Now, engineers are trying to make the next leap to craft that can fly more than five times the speed of sound. But it is proving difficult.

The most recent test flight ended in failure on Tuesday when a faulty control fin caused the US Air Force X-51 Waverider jet to lose control and crash into the Pacific Ocean.

The missile-like vehicle - powered by a supersonic combustion engine known as a scramjet - was dropped from a B-52 bomber off the coast of southern California It was supposed to be propelled by a solid-rocket booster, then ignite its scramjet engine to reach speeds of up to Mach 6. In the end, the test flight lasted just 31 seconds.

It was the last of three planned tests of the X-51, designed to demonstrate the feasibility of a hypersonic missile. It now joins a long list of failed hypersonic flights that show just how difficult it is to reach these so-called hypersonic speeds, usually defined as Mach 5 or above.

‘Rush to failure’

The appeal of hypersonics is simple: imagine an aircraft that can travel from New York to London in under an hour, or a missile that can reach anywhere in the world in less than two hours. But military experts have long cautioned that missiles, rather than reusable aircraft, are likely to be what will be developed first.

An air-to-air missile or an even an air-to-ground missile is the most likely near-term application for hypersonics, says Werner Dahm, director of Security and Defense Systems Initiative at Arizona State University, and a former US Air Force chief scientist. “It’s technologically much more achievable in the near to midterm,” he says.

Engineers have taken a variety of approaches to hypersonic aircraft over the years: the X-51 is called a WaveRider because it literally rides its own shock waves, and is powered by a scramjet, a variation of the traditional ramjet engine, where the exhaust from fuel combustion is compressed as it goes through the engine. But the Pentagon has also looked at a number of rocket-boosted gliders, and more complicated reusable aircraft powered by combination turbine and ramjet engines, among other designs.

But even building a test vehicle has proved difficult: the first X-51 flight test was cut short due to a flight anomaly, and the second test failed after the vehicle didn’t separate from its rocket, as planned. Yesterday’s failure is likely to raise even more questions about the future of hypersonic efforts. “Hypersonics test and evaluation is extremely unforgiving of miscalculation and error,” says Richard Hallion, a former senior advisor to the Air Force, and a leading expert on hypersonics.

Indeed, hypersonics has a mixed history, littered with the bodies of cancelled test vehicles, particularly those that have proved too ambitious. Hallion says many hypersonic research programs have suffered from a “rush to failure”, where flight vehicles have been flown too early, and then failed not because of an inherent problem in the vehicle, but because of a simple engineering mistake.

Most memorable, perhaps, was the 1980s-era National Aero-Space Plane, which was touted by President Ronald Reagan as a new Orient Express that could travel from Washington, DC to Tokyo in two hours, reaching speeds of up to 25 times the speed of sound. But the test aircraft, dubbed the X-30, proved too costly and vastly too complicated for the technology at the time.

More recently, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa), the research and development arm of the Pentagon, tried to revive the idea of a reusable hypersonic aircraft through a program called Blackswift, though it was soon canceled, after Congress questioned the ability to engineer such an aircraft, given previous failures.

But that has not put them off the idea of hypersonic flight. The Pentagon also recently started work on the High Speed Strike Weapon, a hypersonic missile that will be launched from an aircraft. “It’s the next step,” says Mark Lewis, a former Air Force chief scientist, who was involved in the X-51 effort. “It’s looking at making hypersonics more operational and practical.”

Another programme is also underway: Darpa, which has also funded the X-51, held an open meeting this week for those interested in bidding on a new hypersonic program, which according to the agency announcement, is expected to lead to a hypersonic “X-plane” in 2016.

‘Monumental challenge’

The programme, however, is based on the design of the Falcon Hypersonic Test Vehicle-2, or HTV-2, an unmanned glider that can travel at speeds of up to Mach 20, but suffered two previous catastrophic failures. The HTV-2 was designed to be launched off a rocket, and then glide, unpowered. But in its first flight, the vehicle began to spin like a football eventually crashing; the second flight also failed.

HTV-2 was once considered as a candidate for a mission known as “Prompt Global Strike,” a weapon that could travel anywhere in the world within an hour.

For critics of the HTV-2, Darpa’s decision to continue with a vehicle that already failed twice in flight for apparent design failures is a repeat of mistakes made in previous hypersonic programmes. “It’s a bad design. It flew twice, it was lost twice,” says Hallion. “No matter how much lipstick you put on this pig, it’s still a pig.”

Some advocates of hypersonics, however, believe that the real problem with the government and military programmes is that they try to do much, and then simply cut off support when things go wrong. “You cannot achieve this until you commit yourself to doing it,” says Preston Carter, who previously managed hypersonics programs at Nasa, Darpa, and the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in California,

Carter is now in the private sector trying to find funding for a commercial aircraft designed to travel at speeds of around Mach 5, which would make the trip from New York to London in about half the time that it took the Concorde.

Hypersonics is challenging, Carter acknowledges, but it’s not impossible. He points to previous aircraft, like the SR-71 Blackbird, a supersonic spy plane, and the civilian Concorde that, though not hypersonic, pushed the envelope of what was technically possible. Those aircraft also had seemingly monumental engineering challenges at the start, but they eventually succeeded, Carter says.

The same approach needs to be taken to hypersonic aircraft. “The reason why they were able to do it because they started,” he says. “The reason we won’t do it is because we haven’t started.”

If you would like to comment on this article or anything else you have seen on Future, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

This story was updated at 2010GMT on 15 August to state that a faulty control fin caused the failure of the X-51.