The men who mine the ‘Devil’s gold’

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTEIndonesia’s Kawah Ijen volcano is famous for its blue flames. But to locals, it’s the sulphur within its depths – known as the ‘Devil’s gold’ – that provides its true value.

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTEKawah Ijen is a volcano found in eastern Java, Indonesia. At night, it comes alive with blue fire as its sulphur deposits catch light. Tourists flock to the volcano to see the blue flames.

But the famous sight has a darker side.

“Very few people know about the human story of that crater, and the hardship and sacrifice that is happening there,” says photographer and photojournalist Aurelie Marrier d’Unienville, who visited the volcano this year. (Photo credit: Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE)

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTEThe sulphur that creates the blue flames is also at the centre of a thriving – and back-breaking – industry. Sulphur is a valuable commodity, used in a range of goods and processes. In Java it is used in matches and to make sugar whiter, among other things.

The molten sulphur is tapped from inside the rock using metal pipes that bring it to the surface where it cools into a hard, yellow solid. The miners call this solid sulphur ‘Devil’s gold’. That’s partly because of its colour and because it is a source of income. But it also reflects the fact that those who rely on it for money pay a heavy price with their health. (Photo credit: Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE)

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTEIjen is the one of the few places in the world where sulphur mining is still done by hand.

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTEThe miners’ journey starts around midnight, when they get on their motorbikes to ride to the volcano. The bikes can take them as far as the foot of the crater. From there, it’s about a 2,800m hike up to the top. “Then they descend down into the crater, avoiding lots of loose rocks and jagged stones. That’s the beginning,” says Marrier d’Unienville.

The men break apart the solidified sulphur, hacking it into lumps the size of small boulders. They collect the sulphur in wicker baskets balanced on a pole across their shoulders. But as brutal as the work is, the most gruelling part is the return journey. “They have to carry more than their body weight back up the crater,” Marrier d’Unienville says.

The mining doesn’t just take its toll on the men’s backs and joints. The air is acrid and thick with noxious fumes, which form when sulphur reacts with oxygen and water. “As you descend you realise how toxic and harsh this environment actually is,” Marrier d’Unienville says. “The air is so harsh your eyes don’t stop watering and you can hardly breathe.” (Photo credit: Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE)

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE“When you are in the crater you hear constant coughing.”

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

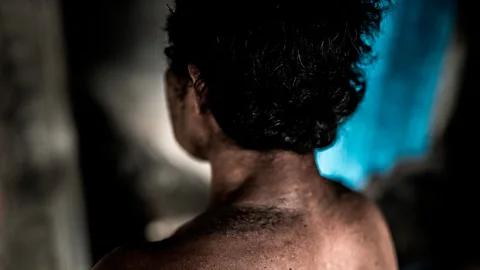

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTETourists visiting the area often wear gas masks to protect their airways. But most of the miners cannot afford masks, so they work with just a handkerchief or damp cloth to cover their noses and mouths. More than half of the miners suffer from pharyngitis – inflammation of the back of the throat – and a third experience respiratory diseases every month. As well as scars on their backs from carrying the heavy loads, as shown here, the men often develop deformations of the spine and legs.

The miners have difficulty getting treatment for the work-related health problems they develop. It is a long journey into hospital, meaning that basic medical care is sometimes impractical. Instead, the miners often retire early when their health fails. The area’s younger men then have the added responsibility of supporting their fathers who are no longer able to work because of their health problems, as well as the rest of their families. (Photo credit: Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE)

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTEOn a good day, the men get paid around 145,000-220,000 Indonesian rupiah ($10-15). There are few other options for employment in this remote part of Java.

“There used to be some agricultural jobs, but the pay was even lower. There are no other jobs in that area,” says Marrier d’Unienville. “There’s a lot of pressure on the men for the income from mining to support their families.” (Photo credit: Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE)

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTEIn most other parts of the world, sulphur mining doesn’t take place at an active volcano site. More commonly it’s collected as a by-product at oilfields. The process is highly mechanised and the heavy lifting is done by machines. Labourers at other sulphur-mining sites, such as Canada’s oil sands, have better access to adequate protection.

The miners of Ijen want to be the last generation to mine sulphur by hand here. They say they want to earn enough money to send their children to school, to give them other options besides sulphur mining. “The work is really, really hard, but the men often say that it is a sacrifice they are willing to make for their families – specifically for their sons,” says Marrier d’Unienville. (Photo credit: Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE)

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE

Aurelie Marrier d'Unienville/INSTITUTE“They wanted their sons to be the first generation that didn’t have to go through what they went through.”