Comedy on 'prescription': Why performing stand-up is good for your health

In the UK, new schemes to support mental health are introducing to people an unexpected skill: stand-up comedy.

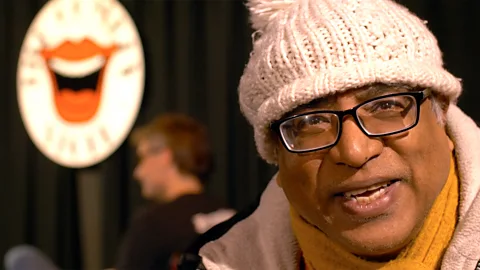

Mohan Gupta had never dreamed of becoming a comedian. Born in India and educated in the UK, he trained as engineer and, later, a monk. "I never in my life thought I would make anyone laugh," he says.

But a few years ago, after suffering a nervous breakdown, Gupta's doctors prescribed him something unusual: a stand-up comedy course.

Laughter has long been linked to a variety of health gains: it can both reduce stress, and increase immunity, focus, and cardiovascular function. Yet research now suggests that not just consuming comedy, but actively creating it – especially in a group setting – can offer significant benefits to mental health in particular.

In the UK, new programmes are beginning to use stand-up comedy lessons to help people in distress. They come as part of a larger global movement of social prescribing: a process through which health workers refer patients to non-clinical, community-based resources and activities, as a way to both improve patients' long-term health and reduce pressure on healthcare.

Gupta, who was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and was initially prescribed medication and hospital rest, received his social prescription through a course called Comedy on Referral – a 10-week programme teaching students how to write and perform a 10-minute comedy set about their lives. Launched in 2020, the course was the first of its kind to be funded and prescribed via the NHS.

Joe Bor

Joe BorAngie Belcher, the Bristol-based comedian who created and teaches the course, describes her goal as helping her students "find their banana" – their comedic source of pain, whether that's going through a divorce, struggling with parenthood, or recovering from abuse. "Your comedy doesn't come from the nice bits about our lives. It comes from the bits that are difficult," she says.

Finding the "funny" in something doesn't mean it's not serious, Belcher adds. "It's about doing what we need to do to get [through those difficult bits]."

That's what Gupta says helped him recover from his nervous breakdown and being admitted to hospital. He's found one of the course's greatest gifts has been connecting with his fellow comedians. "They got me out of myself, and they really did get me to make people laugh for the first time."

Comedy's ancient cure

Laughter is one of our oldest survival tools, explains Ros Ben-Moshe, an adjunct lecturer at La Trobe University and author of the book The Laughter Effect. "From the East to the West, humour appears as a tool for connection, wellbeing and emotional support."

Ben-Moshe points to several historical examples of the restorative role humour played in early civilisations – including indigenous groups using clowns to relieve tension, and ancient Greek physicians prescribing visits to comedians. She attributes these anecdotes to the role humour plays in developing healthy societies and families. Early humans who laughed together formed safer, more cooperative groups, while parents and infants use laughing and smiling to strengthen their attachment, she explains. In both cases, "laughter reduces tension, signals safety, and helps maintain cohesion," she says.

"Humour is one of our most natural and accessible stress busters," she adds, pointing to the ways laughter triggers the release of mood-boosting neurotransmitters and hormones.

Laughter as therapy

A wide body of research has explored this relationship between laughter and wellbeing. One small study from 1989 measured the blood samples of participants before and after they watched a humorous video; compared with the control group, they had significantly reduced levels of the stress hormones cortisol and epinephrine. Another paper demonstrates how laughing produces β-endorphins, which help reduce inflammation and blood pressure. And a 2013 review of nearly 80 years of research associated laughter with a wide range of health benefits, including improved pain thresholds and lung function (while also noting a rare risk of physical harm, such as jaw dislocation or trouble breathing).

Some studies additionally suggest there's a special psychological benefit in using humour to re-evaluate stressors in our own lives. A survey of 258 undergraduate students found that those who reported having a "high sense of humour" also reported less stress and anxiety than the low humour group – suggesting humor can "restructure a situation so it's less stressful," the study reads.

Another that recruited older people to participate in a four-week, stand-up comedy intervention found the participants not only increased their concentration of the mood-boosting neurotransmitter serotonin, but also reported less depression and improved sociability.

More recently, researchers have also begun to explore how humour can be used as a tool to help people with mental health problems, specifically. A 2023 review of studies into this application called for more research, yet concluded that there exists "some promising evidence for comedy interventions on mental health". It noted a range of mechanisms through which humour promotes healing, including increasing self-esteem, reducing hostility and seriousness, and strengthening mutual bonds in social relationships, among others.

Joe Bor

Joe BorStand-up for wellbeing

For Angie Belcher, the understanding that shared laughter can help you get through hard times comes from personal experience. When her mother was diagnosed with dementia, she worked with her brother to find the lighter side of the situation. "Laughter has that ability to make it seem like you can carry on," she says.

Her comedy-on-referral courses now help her students do likewise, by facilitating games and exercises that can tap into their deepest vulnerabilities and insecurities. "I'm not trying to make you into the archetype of a stand-up comedian. I'm trying to get you to lean in to what your thing is – maybe it's that you're quiet or you're nervous – and play with that," she explains. "In order to find out who you are on stage, you need to find out who you are off the stage."

Belcher says the group element is key. "The fact that, in 10 weeks, you've got to go on stage and try to make people laugh – it sort of unites everyone together in their fear."

That kind of self-discovery and group-bonding was unexpected for Ryan Moore, a football coach and former player who had struggled with addiction and been diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder. After four years of therapy, Moore decided to give Belcher's comedy-on-referral course a try. On his first day, he wasn't sold. "I was the youngest guy there and I looked around and wondered if this was beneath me," he admits. But then, as the men started talking about their traumas, his mindset shifted. "It was like an arrow had gone through every single person's heart and I realised we're all sort of the same."

Moore says the comedy prescription has been better for his mental health than any other kind of therapy or pill. And more than just comedic skills and coping mechanisms, he's made friends he otherwise wouldn't have. "It's really special to have that connection with guys I would never meet or speak to in a pub."

Moore says the group has also helped him shift his perspective on himself. "There's this victimhood mentality where you carry [your pain] around on your shoulders and it weighs you down every single day," he says. "But here, we can get that feeling off our chest and have a laugh at the things that have happened to us."

In a report analysing Belcher's comedy-on-referral programme for men, co-author Lisa Sheldon, a consultant, clinical psychologist and a leader within the West London NHS Trust, also recognised this group dynamic. Among other benefits, she says, it involves "talking publicly about what it means to be human and being open about what goes on inside of us, whilst at the same time dispelling myths and establishing shared truths and connection".

The report also says using humour as a therapeutic tool, rather than framing the course as therapy, helped to "facilitate a lighter perspective on past traumas, thus lessening the burden of anxiety and fear".

Belcher agrees that the lighter framework was key. "If I'd asked these men, 'Do you want to come to a therapeutic men's school?' they wouldn't do that, but when we said, 'Come and learn stand-up comedy,' that worked," Belcher says.

The rise of comedy on 'prescription'

The need for therapeutic tools has grown more urgent in England, where rates of mental illness have continued to rise. The most recent data finds one in six people over 16 in England experienced symptoms of a mental health problem in the past week. The Office of National Statistics found the rate of suicide rose to more than 6,000 deaths in 2023 in England and Wales – the highest since 1999, with rates among men particularly high.

That's part of the reason why the NHS has increased its investment in social prescribing. Though not explicitly measuring comedy prescriptions, a 2022 NHS England-commissioned evidence review from the National Academy of Social Prescribing linked participation in creative and expressive activities with a wide range of benefits – including increased social interaction, decreased stress, healthy behaviours and improved employment.

Joe Bor

Joe BorWhile other social prescribing interventions may use laughter as a tool, Belcher's course seems to be among the few in the UK offering stand-up comedy lessons specifically. In 2022, she partnered with Wellspring Settlement – a charity in the English city of Bristol – for a pilot inviting local GPs to refer patients to the course. In 2023, with support from the Central and North West London NHS Trust, she expanded the course to serve men at-risk of suicide.

Outside of these NHS pilots, she's also worked with charities to bring versions of the workshop to child sexual abuse survivors and LGBTQIA+ community members, among others. And recently, Belcher was invited to share her work abroad in Estonia, bringing six of the course participants, including Moore, to talk about the power of comedy-on-prescription to build mental health, and perform two sold-out stand-up shows.

Despite its expansion, Belcher's course hasn't been without its hiccups. She says it sometimes takes a group longer to reveal their vulnerabilities, and she's had to learn to adjust her pace. Other times, she finds a person takes the course too soon and needs more time and distance from their traumatic experience.

More like this:

• Why singing is surprisingly good for your health

• Our 2,500 year-old mania for personality types

• The books that help – and harm – mental health

But perhaps the biggest hiccup of all has been its popularity. Mohan Gupta had to wait two years before getting a spot in the course.

That demand could partially explain why comedy-on-prescription programs are expanding. This year, the tech company Craic announced it received NHS support to facilitate a comedy-on-prescription program, working with comedy professionals to offer stand-up workshops, live gigs and more.

But for those who can't access formal comedy prescription, Ben-Moshe offers tips for people to use humour as a tool to cope with stress and spark joy. "Each day, ask yourself: 'Where was there a moment of levity, silliness or playfulness today?' Write it down or share it, since this trains your internal humour radar."

If possible, she suggests people make it a habit to share a funny story, joke, or video with those around them. "Laughing together strengthens bonds and multiplies the joy. Even sharing a silly meme can create a ripple of positivity."

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.