What's the best way to learn a new language?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesKrupa Padhy uncovers how we really learn foreign languages – in a dual challenge involving both Portuguese and Mandarin.

There was a time when my oversized hardback Collins Roberts French dictionary took pride of place on my bookshelf of my student accommodation. I owned an edition from the late 1980s, almost 1,000 pages long, handed down from my elder brothers. It travelled with me to Paris in the early 2000s, taking up half the space of my little case as a non-negotiable.

It was a sad day when a decade later, bursting at the seams of our one-bed flat with two babies, I decided it had to go. It had gathered dust since leaving university but had equally screamed that I had once been serious about language-learning.

Multilingualism has always been a part of my fabric. I was born into a Gujarati-speaking household, my Indian-origin parents having immigrated to the UK from Tanzania in the 1970s. My reading and writing skills were topped up with lessons at the local temple every Saturday as a kid. In 1995, Zee TV arrived in the UK on cable network, and I became hooked on watching cheesy Hindi serials every evening with the subtitles on. I took French to degree level and headed for my year abroad to Paris. Finally, a tinge of Spanish came to me after a few terms of evening classes. All these languages (bar the holiday-Spanish) have taken time and commitment.

Understandably maybe, I've reacted reluctantly to the countless advertisements on my Instagram feed promising to teach me a language in 30 days (if not sooner) by giving up less than 30 minutes a day.

The benefits of language-learning for our long-term brain health and happiness are well noted, so no regrets there. But had my four years of studying a language to degree level conjugating verbs and memorising vocabulary become an outdated way of learning? (Read more about the benefits of bilingualism here).

Krupa Padhy

Krupa PadhyAlong with the promise of becoming fluent at lightning speed, a range of new methods and technologies have transformed how we pick up languages in an increasingly time-poor age. One is "microlearning", an approach that breaks down new information into small chunks that are meant to be absorbed quickly, sometimes within minutes or even seconds. It's rooted in a concept known as the forgetting curve, which states that when people take in large amounts of information, they remember less of it over time.

In addition, there's a wealth of new technologies, from chatbots offering instant feedback, to virtual reality and augmented reality technologies which drop you into conversations with virtual native speakers. However, some argue that the promise of fast fluency misses crucial elements of actually learning to speak to people in another language, such as developing cultural understanding and nuance.

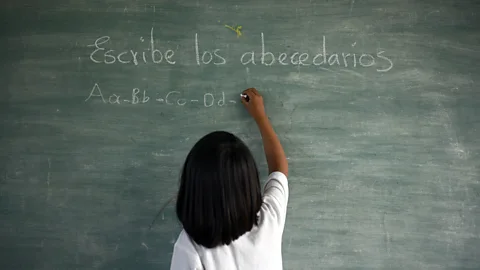

So, with all this choice, what's actually the best, science-backed way to learn a language? To find out, I teamed up with two researchers at Lancaster University's Language Learning Lab: Patrick Rebuschat, a professor of linguistics and cognitive science, and Padraic Monaghan, a professor of cognition in the department of psychology. They let me try out an experiment they designed to mirror language-learning in the real world, and reveal how our brain picks up and makes sense of new words and sounds. The tasks basically simulate how we would cope if we were dropped into a foreign country with an unknown language, and just had to use our innate skills to figure out the new, mysterious sounds around us, and start to make sense of them.

Having not learnt a language in two decades, I was about to learn some Mandarin and Portuguese. Over six days I would be spending just 30 minutes per day on the tasks and tests. I was to complete them, not ask any questions and wait until the end of the experiment for feedback.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMonaghan explains that such experimental studies are used to establish how people begin to get a foothold in a language.

I was intentionally not told from the outset what the tasks were about. But the researchers later explained that they were designed to activate my brain's cross-situational learning (CSL) skills: that's our natural, instinctive ability to use statistics to gradually work out the meanings of words and basic grammar. You can learn more about statistical learning in language acquisition here, but it is essentially our brain's inherent ability to recognise patterns and regularities in speech (such as which words pair well with each other) based on the frequency of their use.

"People can learn very, very fast simply by keeping track of the statistics in the environment," says Rebuschat. "This type of task is designed to mimic real-world learning under immersion settings, where things are often ambiguous and we rarely receive immediate feedback."

Ahead of starting the experiment, I assumed that with my prior knowledge of French and basic Spanish, Portuguese would come naturally. Mandarin on the other hand was for me as foreign as a foreign language gets.

I'd also predicted that as I had done with most of my other languages, lesson one would comprise of basic greetings. Far from it.

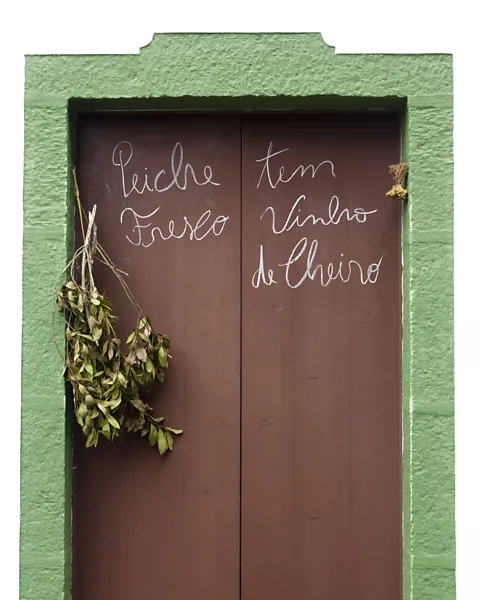

"If you were dropped into Portugal, Brazil, or another Portuguese-speaking country, the language you encounter would not unfold in a tidy pedagogical sequence starting with greetings," explains Rebuschat. "Instead, you would hear a wide range of language in context: people ordering food in cafés, conversations on the street, a football commentary in the background."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThus, my exercise with Portuguese was to choose whether the word or sentence I was hearing matched one of two scenes, both featuring animated animals. This continued on repeat across three days, an example of statistical learning in action, says Rebuschat. "It is a basic learning ability that humans use from infancy – before infants know any language at all – to pick up patterns in the world around them. We use it to learn regularities in sounds, images, and events over time."

I was quick to lean on my prior language knowledge. I know for example in Hindi saap means snake, and upon hearing the word sapo and seeing a frog on the screen, I matched the word to the image.

Soon after, I figured out that each noun appeared in both singular and plural forms performing one of four physical actions like pushing or pulling. The grammar was somewhat trickier but not unfamiliar from the French I had studied.

By day three of Portuguese, results showed my accuracy sat consistently between 90–100%, which I was told was higher than the typical English-speaking learner (presumably, because I was able to use those insights from my other languages). My brain was extracting meaning based on the frequency upon which the same nouns and verbs were appearing on screen.

Getty Images

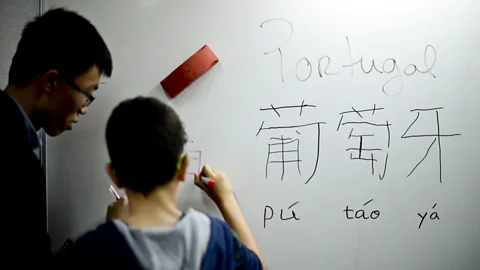

Getty ImagesMy Mandarin learning journey started out somewhat differently.

As with Portuguese, I completed four short tasks and tests each day, but this time I was matching 12 incomprehensible sounds to images of 12 never-seen-before objects. As I later learnt, these weren't real objects or real words. What I was saying out loud were in fact Mandarin tones, which are a core feature of the language as a different tone can change the meaning of a word.

Each made-up word was assigned to a specific object. Using artificial words, known as pseudowords, allows researchers to compare results and improvements fairly because students can't draw on prior knowledge.

At times, repeating the same tones made me comatose and admittedly, I came to my answers with zero scientific reasoning. Lu-fah for example sounded like a loofah which I matched with an object that had soft spikes!

Linguistics students who are native speakers of Mandarin at Lancaster University looked at how I did. By the end of my first session matching the pseudoword to the right made-up object I had reached 75% accuracy, rising to 80% in sessions two and three.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMy production test results (where I was asked to say the tone out aloud) were not as impressive, ranging from 38% rising to 55% by the third day, although I was reassured by Rebuschat that my scores were far above chance.

More like this:

• The language that doesn't use 'no'

• Why we can dream in more than one language

• How toddlers in Finland are saving an endangered Sámi language

Both Rebuschat and Monaghan concluded that I am in good possession of the building blocks needed to pick up languages well. These include having a good ear and being able to pick up subtle differences such as pronunciation, intonation and rhythm. My previous language-learning experience also helped me to recognise recurring patterns and features.

"A third factor, likely just as important as language-learning experience, is memory capacity," Rebuschat tells me. "Unlike the Mandarin study, which used isolated pseudowords, the Portuguese CSL task required you to process and hold entire sentences in mind (determiners, nouns, verbs, number marking) while comparing them to two animated scenes. This places a substantial load on temporary storage, sequencing, and retrieval."

Considering my decent report, would I be on course to learn at least one of these languages to a good standard in a matter of days?

"Achieving fluency in the real world requires sustained exposure, interaction, feedback, and social use over many months or years," says Rebuschat.

He also points me in the direction of the US Defense Language Institute's Foreign Language Center, which provides some of the most intensive language training available. From Persian to Japanese, even with up to seven hours of learning per day plus homework, it takes around 64 weeks to reach basic professional proficiency.

In order to take my learning to the next level, the experts also make the case for traditional human instruction, something that is under threat at many schools and universities.

Rather than seeing new technologies as a threat to human teachers, Rebuschat considers them as complimentary, offering students additional practice and feedback, and widened access.

Monaghan also points out that learning to speak is one thing, but understanding what is said back to you is quite another.

"An interesting feature of language is that 70% of [a given] language is composed of just a few hundred words," says Monaghan. "But what isn't possible quickly is being able to understand what people say back to you, because they'll be using those other, rarer words now and then."

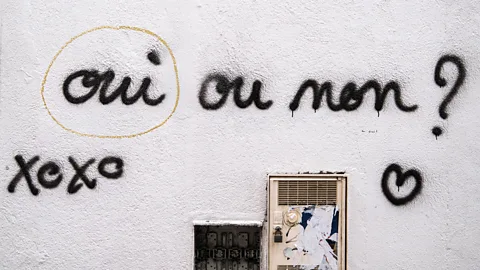

How else but through human-to-human interaction for example would I know that in Gujarati when my elders say "maru loi na pee" ("don't drink my blood") they are actually asking me not to annoy them? Or understand the practical phrase "ça a été" in French, which translates "as it has been", but in conversation is one of the most versatile ways of expressing something was well?

Monaghan stresses that such intricacies throw into question some of the big promises made by new language learning technologies.

"It's not going to replace that really high-level study of a language," he says. "Being able to speak English and being able to read books in English doesn't end studying English literature at university." His words bring this nostalgic linguist some comfort. Whilst the dictionary may have gone, the yellowing copies of works by Jean-Paul Satre, Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire still have a safe space on my bookshelf for now.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.