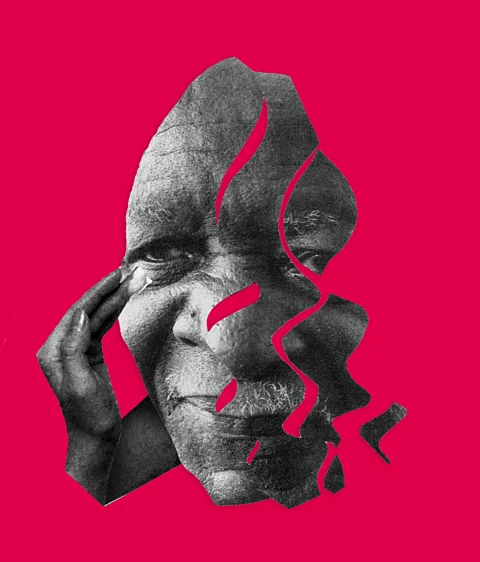

Wrinkles as 'badges of honour': How to embrace an ageing face

Serenity Strull/ Getty Images

Serenity Strull/ Getty ImagesMuch like our other organs, our skin begins to age from the moment we are born. In a world obsessed with youthfulness, here's how you can look after your skin while embracing an ageing face.

On Mount Olympus, sometime around 800-900 BC, the gods and goddesses of Ancient Greece were served sweet nectar and ambrosia by Hebe, the goddess of immortal youth. A beautiful young woman, Hebe was symbolic of being in the "prime of life". Her counterpart, Geras, the god or spirit of old age (hence the English words "geriatric" and "gerontology"), was depicted as a haggard, wrinkled man, often leaning on a walking stick. Instead of beauty, he represented biological decline, and the fear of death. Together, Hebe and Geras are just one of the many representations of ageing in our culture and history that serve the reminder: no one can escape the passing of time.

Humanity's obsession with youthfulness has only intensified since Ancient Greece. Our skin, a living ecosystem, is at the centre of this – not only is it the largest organ in the body, but it's also visible – or as one group of researchers in France put it, "social". In fact, in their study of 1,300 people across 54 countries and five sociological age groups (Gen Z, millennials, baby boomers, Gen X and the silent generation), 85% of participants felt that their skin reflected their personality, suggesting it is tied in with their sense of self.

Much like our other organs, skin ages from the moment we are born – so the fight to keep it looking soft like a baby's is an expensive one. As of 2024, the global anti-ageing products market size was valued at approximately $52bn (£40bn) in 2024 and is expected to reach $80bn (£63bn) by 2030. But why do we try to resist an ageing face and how can we embrace it?

How our skin changes as we age

Our skin is incredible, really. While only a few millimetres thick, it makes up about 15% of our total body weight.

"The skin is a very important organ that we take for granted, even though it's the organ we wear externally," says George Murphy, a professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School. "The skin protects us – it's the major interface to the external environment, which is often hostile."

Our skin acts as a barrier from germs, infections and physical trauma, or anything else that might harm us, like UV from the sun. It also regulates our body temperature and produces hormones and vitamins. "It does so many different things that are absolutely critical to life," Murphy says. "If you lose most of your skin, usually that's fatal."

Our skin ages both intrinsically (inevitable, chronological ageing) and extrinsically (due to our external environment). In both cases, our collagen levels (a protein in the body important for skin structure) decrease and our blood vessels become more fragile.

"What happens with our skin when we age is that it loses many of the structural and functional components that are designed to protect us," says Murphy. Over time, our stem cells start to regenerate at a slower rate, which affects the functioning of each of the three layers of the skin – the epidermis (the outer layer), the dermis (the middle layer) and the subcutis (made of fat and connective tissue). Essentially, our skin thins, dries and loses elasticity. This explains why as older adults, our skin is less able to protect us – for example, wounds take longer to heal.

Of course, some changes are noticeable – like dark spots, loose skin and wrinkles. Wrinkles, creases or folds in the skin, may appear for a variety of reasons: sun damage, smoking tobacco, and of course, natural ageing – with our skin losing elasticity, some wrinkles become static, meaning they're always there. You might see your facial structure change with age, too. Foreheads may appear bigger as hairlines recede, lips become thinner and the tips of noses might droop as the connective tissue supporting the nasal cartilage weakens. Jowls, the fleshy pieces of skin, sag around the cheeks and chin as our jawline loses definition.

Embracing an ageing face is challenging

It's no surprise, then, that as our skin and faces age, it can affect us psychologically. And unpleasant-sounding words like "jowls" do not help.

How we process an ageing face can differ between cultures, ethnicities and genders. Generally, there's not as much research on body image through the lens of ageing with middle-aged or older adults, says Beth Daniels, director of the Centre for Appearance Research at the University of the West of England. The limited research that has been done also lacks in diversity and has tended to focus on white Europeans, she says. "We know less about ageing and how that might translate into facial satisfaction from people with different cultural and ethnic backgrounds."

Serenity Strull/ Getty Images

Serenity Strull/ Getty ImagesOne thing we do know, however, is that while older people are generally more inclined to accept their bodies as they age, male and female experiences of body image are different, typically because female beauty standards are more strongly tied to youthfulness, particularly in Western societies. This has sometimes been referred to as the "double standard of ageing", where women face greater pressure to keep looking young with age.

In one qualitative study on how men and women perceive their bodies through the lens of ageing, for example, men focused on the "functionality" of their bodies, whereas women focused on "display" – and believed that ageing has a negative impact on their attractiveness.

"A different pressure comes with overvaluing youth," says Daniels. "When we look at cultural beauty ideals, they tend to reflect young bodies and faces. As we age, we get further away from that."

Carolyn Karoll is a psychotherapist specialising in the treatment of body image concerns and eating disorders – she helps clients who struggle to accept their ageing bodies. "Beauty ideals are socially constructed – I find that really helpful for my patients. The good news is that, because they're socially constructed, they're not truths. And that means that we can push up against them and construct our own narratives."

Some studies have shown that as women age, they begin to care less about their appearance – with some labelling their facial creases as "badges of honour". However, research also shows that women are inclined to undergo beauty and anti-ageing work such as cosmetic and non-surgical cosmetic procedures to fight against invisibility, the desire to attract or retain a partner and employment-related ageism.

"I think that it's important to stress that individuals are not to blame for feeling that [anti-ageing] pressure, because it's real," says Daniels. "And it can interfere, for instance, even in the workplace, where older employees may be discriminated against because of grey hair and wrinkles, and the assumption that they're older and less relevant."

This isn't to say that some men don't feel that pressure too. Some studies have shown that male body image does also become more negative with age. In the US, across 2024, 7% of all plastic surgery patients were male, and in the UK more men are turning to cosmetic procedures like face and neck lifts, which tighten and lift the skin. In fact, face lifts are becoming increasingly popular for both men and women in the UK and US, with younger people also turning to the procedure.

More like this:

• The curious ways your skin shapes your health

• Why later life can be a golden age for friendship

• Is anti-ageing possible and would we want it?

Anti-wrinkle injections such as Botox are also common. The American Association of Plastic Surgeons recorded almost 10 million neuromodulator injection procedures (an injectable medication like Botox which relaxes nerves) in 2024, across the US. Ninety-four per cent of these procedures were carried out on women. If we inject Botox into our skin, Murphy says, we may get fewer wrinkles because we're paralysing some nerves, "but these aren't permanent physiological remedies that tackle the jugular of the underlying biology of what is causing skin ageing. It's more or less putting a band-aid on it". Nonetheless, he says that "people will get short-term benefits from these approaches".

How taking care of your skin can help

There are ways you can look after your skin, which may in turn help with process of seeing it age. "The problem is, obviously the public views the skin not as a functional organ but as a cosmetic organ that we wear externally," Murphy says, emphasising that we should show great appreciation of our skin and everything it does for our overall health.

His top tips to protect your skin are to avoid any excessive sun exposure, to keep the skin moist, hydrated and clean, and to have a good diet. Eating a wide range of foods that are vitamin-rich and contain essential fats like omega-fatty acids can benefit your skin as it ages.

Serenity Strull/ Getty Images

Serenity Strull/ Getty ImagesMiranda Farage is a clinical dermatotoxicologist, a scientist who studies how toxic substances affect the skin, at Procter and Gamble in the US. She says that while we can't do anything about genetics, our lifestyle choices – nutrition, exercise, but also stress-management and mindfulness – all impact our skin health, and in turn our wellbeing. Maintaining social connections like friendships to reduce social isolation may also help with embracing an ageing face, she says.

The way each of us psychosocially adapts to ageing depends on our genetically determined personalities, as well as our early developmental influences and later life experiences. So what's also important, Farage says, is "educating people to embrace the change and stay resilient", she says. "Every life stage is a beautiful stage if you move with it."

As a society, she adds, our attitudes towards ageing faces and ageing in general need to change. "We cannot keep this pressure… [the question of] how we shift society to start thinking differently – that's what our job will be."

Some things, however, are easier said than done. So if you find yourself thinking negatively about your ageing face, Karoll also has some practical advice.

Firstly, softening your inner dialogue is important, she says. Instead of judging your reflection, be curious and objective – and don't look at your ageing face as something to be fixed. "Taking this stance of self-compassion, or even just stating what is happening," she says. "Saying things like, 'I'm noticing my face changing, and that's part of being alive'… This reduces the criticism, but you have to do it consistently, [so it] becomes more habitual."

It's also making peace with ambivalence, Karoll adds. "Accepting an ageing face doesn't mean that you're going to love every change… it just means that you stop fighting reality. It means that you can miss your youthful face… or miss that time of life, but you can also honour the one that you have now."

Ask yourself – who do I want to be as I age? What do I want my presence to communicate? What's important to me? Karoll calls this "anchoring in your values, instead of your appearance".

"It's shifting focus from how we look to how we want to live," she says. "Then ageing becomes something that we don't necessarily have to fight, it's something that we inhabit."

And with that, I'll leave you with a line from Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice:

With mirth and laughter let old wrinkles come.

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebookand Instagram.