Should you always treat a fever? The symptom that puzzled doctors for millennia

Serenity Strull

Serenity StrullFevers are uncomfortable, annoying and occasionally dangerous. But they are also an essential part of how we protect ourselves.

It's 3am and you can't sleep. Sweats and shivers let you know something is not quite right. A furnace-like heat races to your forehead, shivers and chills trickle down your spine. You feel helpless, confused and exhausted. "It's only a fever," you tell yourself.

An evolutionary feature more than 600 million years old, fevers are a common accompanyment of a wide range of infections by viruses, bacteria and fungi. Many of us will have experienced them during a bout of flu, for example. Fever has also been a sign of such serious, and often deadly, illnesses through human history that we have incorporated it into the name we give many diseases – scarlet fever, dengue fever, yellow fever, Lassa fever. The list goes on. (Learn more about how viruses get their names in this article by Sarah Pitt.)

Despite this, humans only reached a full understanding of how our bodies produce fever in the 20th Century.

So why exactly do we get them, should we always treat them – and at what point do they go from beneficial discomfort to a serious problem?

A bit of bloodletting

Our ancestors were fully aware of the danger of fevers, and they fed into interesting ideas of how the body works, says Sally Frampton, humanities and healthcare fellow and historian of medicine at the University of Oxford.

"Today we would know, 'Oh you've got a fever, there's something else going on'," she says. "But for a lot of [people] in the early modern world, and up to the 19th Century, there was a sense that the fever is the disease."

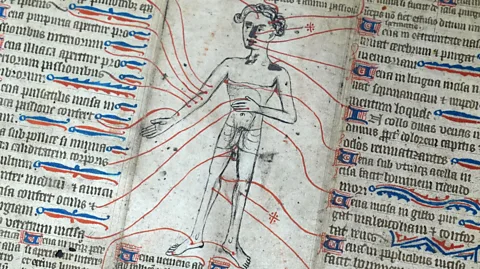

The ancient Greeks treated fevers with everything from starvation to bloodletting, both of which were used up to the 19th Century to try to cool fevers. The big shift in our understanding of fever came after germ theory arrived, says Frampton, when we learned more about infections and fever started being seen as a symptom rather than a disease itself.

Germ theory

Germ theory, first published by Louis Pasteur in 1861, identified microorganisms invading our bodies as the cause of disease. The French scientist paved the way towards our understanding of microbial infections as something we can prevent through cleanliness.

After a surge in maternity deaths during childbirth due to "childbed fever" (now known as postpartum infection) in a Parisian hospital back in 1875, Pasteur proposed that the infection was being spread by physicians and hospital attendants. He promptly told clinicians to wash their hands and sterilise their tools with heat.

We now know fever is part of our bodies' innate response to infection. Found across the animal world in both warm-blooded and cold-blooded vertebrates, the chills when fever settles in, followed by the sticky and relentless sweats when it breaks, is our body's intruder alarm – and attack – system.

Fevers signal that pathogens and other hostile actors are making our bodies their home – and that we're putting up a fight. Unpleasant as they may be, they help us to get rid of these intruders. When unchecked, though, fevers can become harmful.

What is a fever?

A fever is generally characterised by a body temperature above 38C (100F). It can occur as our body's response to infections, but it can also be triggered by auto-immune diseases, inflammatory diseases or after a vaccination.

As our bodies react to the threat of a virus or pathogenic microorganism, such as fungal or bacterial infections, our core temperature rises. This is an important mechanism in our immune response as it makes our bodies less cosy for those harmful pathogens – they struggle to replicate or thrive inside us at these higher temperatures.

"The body senses something strange, like a virus or bacteria. The thermostat is twisted a little bit to increase the temperature to the level that the response to this danger can be more efficient," says Mauro Perretti, a professor of immunopharmacology and inflammation expert at Queen Mary University of London in the UK. "Cells will work better; enzymes will work better. It's a reset, which is going to be transient, of course."

Alamy

AlamyIn our bodies, there are tiny windows between too cold, just right and too hot. When our core temperature drops below 35C (95F, known as hypothermia) shivers, slurred speech and slow breathing are triggered. At the opposite end of the scale, a rise in core body temperature above the normal range for a prolonged period (hyperthermia) can be dangerous and harmful to our internal systems, including the central nervous system, especially when it goes above 40C (104F), and can lead to hallucinations, febrile seizures and death.

Fever's payoff

While fever involves a regulated rise of our internal thermostat (the set point), during hyperthermia the body temperature rises in an uncontrolled way outside of thermoregulatory control. If the perceived threat to the body is defeated, the fever will break. The end of a bout of fever comes when the body has been successful in fighting off an infection, either by itself or with the support of modern medicine, such as antibiotics for bacterial infections. Fever's payoff comes from its short-term nature, as the many systems in our bodies require a return to that sweet spot of around 37C (100F) to operate at an optimal level.

Fever is a pillar of inflammation, which is our bodies' natural response to harms such as injury or infection. Fever, alongside pain, redness, oedema (a build-up of fluid characterised by swelling) and loss of normal function, occurs in affected body parts and systems when your body responds to those threats. Together, these reactions ensure our bodies respond promptly to the danger, whether it is an infectious or a non-infectious risk, says Perretti.

Young children get fevers for the same reasons as adults, often linked to viral or bacterial infections. But they are more susceptible to them, largely because they take longer to calibrate their internal thermostat. What's more, in children, the hypothalamus – a region of the brain which produces hormones that regulate body temperature – is still getting used to responding to pyrogens, substances that trigger an immune response that leads to a rise in temperature.

Pyrogens communicate with the hypothalamus (the region of our brains which regulates the temperature of our bodies), to raise our temperature to a level at which viruses and bacteria struggle to replicate and survive. These microbes tend not to adapt to higher temperatures during bouts of fever, however, since it isn't beneficial to them in the long-term – they would become less efficient at infecting healthy, cooler organisms.

Millennia-long benefit

Despite centuries of trying to get rid of fevers, scientists now understand that in many circumstances their benefits can actually outweigh their harms.

When someone has a fever, the increase in temperature can support immune cells, such as white blood cells, helping them to respond faster to the threat of pathogens. Fevers can also benefit the biochemical and cellular reactions which are part of the body's inflammatory response, says Perretti. As well as turning the thermostat up above the temperature pathogens such as bacteria tend to thrive in, the heat element of a fever works as an alert system, igniting our inner surveillance team into action: our neural pathways and physiological systems chat to each other, conjuring the best plan of action.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOur changes in behaviour during a fever also help to supercharge our body's immune response, says Perretti. Along with other aspects of how our bodies fight an infection, such as reduced blood levels of iron and zinc, reduced appetite and overall lethargy, this forces us to focus on rest and recovery.

Animals as diverse as fish and reptiles also raise their core temperatures during infection for better survival outcomes (cold-blooded animals do this by physically changing their environment to warmer climates: fish swim to warmer waters and lizards bathe in the sun). Fever has been found to give organisms, including people, a better chance of surviving infection.

Too much fever

If our bodies are unable to mount an inflammatory response, such as fever, swelling or redness, we cannot adequately protect the body from infections.

Still, in the case of both inflammation and fever, "a bit is good, too much is bad", says Perretti.

Because fevers can certainly also be dangerous. Persistent high temperatures can lead to dehydration, as our bodies increase the production of sweat to cool us down. If our body temperature gets too high, and stays above 40C (104F) for too long, our vital systems stop functioning correctly. A 2024 study of mice, meanwhile, found that excess heat can lead to DNA damage.

Another concern is febrile seizures, convulsions which primarily impact young children. These are the body's response to a rapid surge in its core temperature, usually when fighting an infection. The exact cause isn't fully understood. Most febrile seizures are unlikely to harm you or cause long-term effects, but it is important to still be checked by a doctor.

Serious complications occur, though, when persistent high fever is ignored as a warning sign of harmful conditions such as meningitis, pneumonia or sepsis. Given this, treating microbial infections with the correct course of action suppresses our need to produce pyrogens and adjust the body's thermostat, since it gets rid of the foreign bodies our immune system would be fighting.

More like this:

• What is the optimum temperature for your health?

• Why your fingers wrinkle in the bath

• How your hormones control your mind

Fever is a powerful but sometimes lethal instrument the body uses to fight infection and protect us. One instance when things turn for the worse is during uncontrolled extremely high fever, known as hyperpyrexia. Such uncontrolled heat can lead to brain dysfunction and even organ failure, both of which can be deadly.

To treat a fever?

So, considering fever is usually helping our bodies fight infection, what happens when we try to get rid of it?

There certainly are potential downsides. As a 2021 review of fever in the Covid-19 pandemic era put it: "blocking fever can be harmful because fever, along with other sickness symptoms, evolved as a defence against infection".

Using medication to quell the impacts of fever can also have adverse effects at a population level. A 2014 study, for example, found that suppressing fevers caused by the flu can lead to higher transmission rates. That's because if infected people simply treat their feverish symptoms, they soon resume their everyday activities, from work to socialising, spreading the disease further than if they felt the need to rest.

In the case of mild fevers, it's therefore better in some circumstances to let them do their job, says Perretti. Theoretically, he says, one could give the body 24 to 48 hours to perform the necessary inflammatory response. However, he warns, this could still be dangerous in some situations, so you should always consult your clinician, who can identify the best course of treatment for your specific scenario.

Scientists are still working out when to treat fevers, and when to leave them alone. But the next time you have one, as the sweat drips from your body and the shivering sets in, take the opportunity to marvel at your immune system's efforts to protect you from further harm. It's been millennia in the making.

* All content within this column is provided for general information only and should not be treated as a substitute for the medical advice of your own doctor or any other health care professional. The BBC is not responsible or liable for any diagnosis made by a user based on the content of this site. The BBC is not liable for the contents of any external internet sites listed, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service mentioned or advised on any of the sites. Always consult your own physician if you're in any way concerned about your health.

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.