Stunning and surprising depictions of Notre-Dame

Alamy

AlamyArtists as diverse as JMW Turner and Edward Hopper have been inspired to capture the spirit and beauty of the iconic cathedral. Kelly Grovier picks some of the finest.

News this week of the devastating fire that ravaged Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris stopped the world in its tracks. Rising above the River Seine, the iconic structure throbs like an elegant engine, its hulking towers pumping at the heart of the city like a pair of powerful pistons. Few edifices in history have become quite so synonymous with the spirit of a place. Cherished for its pioneering use of flying buttresses and ribbed vaulting, the 12th-Century church emerged as the epicentre of Parisian cultural consciousness following the publication in 1831 of Victor Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris – better known in English by the Anglicised title The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

For centuries, the cathedral’s famous facade has teased and tugged at the imagination of great artists, offering itself as a kind of irresistible challenge to their ingenuity and genius. Artists as diverse in temperament and technique as JMW Turner and Edward Hopper, Van Gogh and Matisse have tried to convert into poignant imagery the structure’s energy and intensity. As a way of paying tribute to a masterpiece of muscle and mind that, but for the skill and courage of the firefighters who saved it, the world almost lost this week, what follows is a look at some of the finest, and surprising, depictions of Notre-Dame in art history.

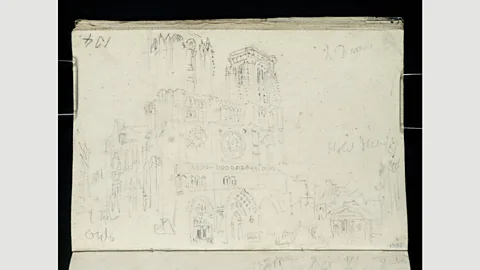

JMW Turner, Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris, 1826

Tate

TateFive years before the publication of Hugo’s famous novel would fix the cathedral in popular imagination as the axle around which the Parisian soul twists, British artist JMW Turner found himself drawn to the ornate allure of the structure’s Western facade. In a sketchbook that chronicles Turner’s tour of the Loire and Seine in 1826, the always ahead-of-the curve artist managed to translate, with relatively few strokes of pencil, the energy of Notre-Dame’s High Gothic frontage, largely complete by the middle of the 13th Century. Given Turner’s fascination with conflagration (his depictions of blazes at the Houses of Parliament in 1834 and at The Tower of London in 1841 are among his most arresting) one can only imagine how the horrifying fire at Notre-Dame this week would have ignited his empathy and imagination.

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Quai des Orfèvres et pont Saint-Michel, 1833

Alamy

AlamyThe influential French artist Camille Corot, whose instinct to paint out-of-doors (en plein air) would inspire a generation of Impressionists, was still struggling to establish a reputation when in 1833, at the age of 37, he captured the dark towers of Notre-Dame, encrusted by centuries of soot and dirt, rising ominously above a jumble of edifices facing the Seine. (The cathedral would not get a proper scrubbing until 1963.) Corot’s painting was very much a transitional piece in the artist’s career, and found him as he began to pivot from the painstaking exactitude of his earlier works to a later lyricism of form and loosening of brushwork that would, in time, elicit the highest praise from Claude Monet: “there is only one master here.”

Vincent van Gogh, The Roofs of Paris and Notre-Dame, 1886

Think of Van Gogh and you think of the anguished golds of his Sunflowers and the whorling, white-knuckled constellations that trouble his Starry Night. But a stint in Paris beginning in spring 1886, two years before the creative breakthrough in Arles that would bring with it the rush of works synonymous with Van Gogh’s name, saw the artist limbering up with a soulful chalk sketch of the city’s stark skyline. Devoting more space to the emptiness of barely articulated clouds than to the solid structures of the world below, Van Gogh’s doleful doodle captured a Paris drowning in existential sadness – its rooftops struggling to keep their heads above a rising flood of scribbled shadow. Amid the gathering gloom, the angular hulk of Notre-Dame (on the left) and the rounded pate of the Pantheon, right of centre, glower at each other like mythic monsters steadying for a fight.

Frank Boggs, Quai à la Seinie, Paris, au Clair de Lune, 1898

Alamy

AlamyA restless spirituality vibrates from Frank Boggs’ moody nightscape, which captures at its centre the jagged snarl of Notre Dame’s towers and spire as they snigger at a cloud-scarfed sky. Born in Springfield, Ohio in 1855, Boggs travelled to France to study when he was 21 and would be lured back, time and again, by the magnetic pull of Paris. Though rendered in oil paint, his poetic tribute to the mysteries of the Paris night has all the shimmering intensity of a hasty watercolour – a medium of which Boggs is an underappreciated master. A miracle of shadow and stingily rationed light, Boggs’ nocturne transforms a city of gritty substance into a whispery underworld of shifting shades and luminous darkness.

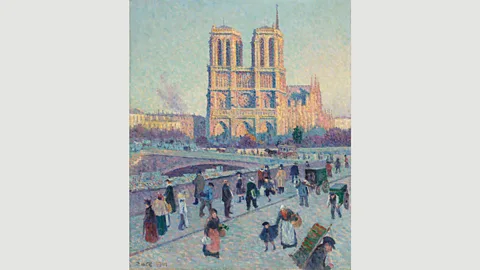

Maximilien Luce, The Quai Saint-Michel and Notre-Dame, 1901

Alamy

AlamyDazzled, as our eyes are, by the extraordinary artistic technique that the painter has used to portray the sun-soaked exterior of Notre Dame – small splotches of colour juxtaposed, side-by-side, so that they blend optically in our mind’s eye rather than materially on his messy palette – it is easy to miss the struggle and stress of the figures nearest to us in the work’s foreground. Maximillien Luce, who created the work in 1901, was an avid anarchist as well as a Divisionist (the name for that painterly technique of contrasting colours, sometimes called ‘Pointillism’) who greatly sympathised with the slumped-shouldered figures in his work, such as the man pulling a cart like an overworked horse. Though Luce was acquitted of being involved in the assassination in 1894 of the French President Marie François Sadi Carnot, the artist, with his little dabs and dots of colourful paint, nevertheless sought to remake the world by blowing it to smithereens.

Edward Hopper, Notre Dame, 1907

Alamy

AlamyWe are so accustomed to equating the bleak music of Edward Hopper’s pensive vision with the infrastructure of Modernist Americana – think of the melancholic coffeeshops in his iconic paintings Nighthawks (1942) or Automat (1927) – that to see Hopper turn his hand to medieval relics of Old Europe is disorientating. But years before Hopper found his voice capturing the urban loneliness of brightly lit cafes, in the first decade of the 20th Century, he made a series of visits to Paris. It was Rembrandt, more than any French artist, new or old, that caught Hopper’s eye as he wandered the city’s museums and galleries. The Dutch master’s heavy brushstroke and muted palette of grubby ochres has clearly influenced Hopper’s portrait of Notre-Dame, seen from the south-east side. Like a terrible premonition of traumas to come, Hopper has cropped the cathedral’s soaring spire, snapping off its endless ascension.

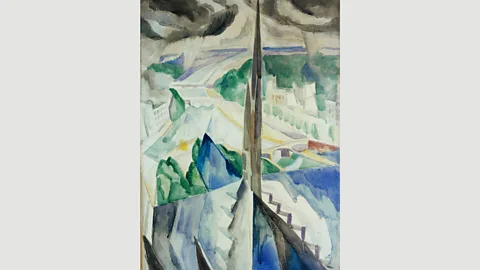

Robert Delaunay, The Spire of Notre-Dame, 1909

Alamy

AlamyWhere Hopper truncates the ascent of the cathedral’s spire, Robert Delaunay focuses our gaze on it as if the spiral were the very needle of our soul’s compass. Created the same year that the artist began work on a career-defining series of paintings that capture the Eiffel Tower in a range of Modernist moods, The Spire of Notre-Dame, with its organic geometry of luminous blues and resplendent greens, pointed towards the poetics of Orphism (an especially colourful form of Cubism, in essence) that would preoccupy Delaunay in the ensuing years. To help observers of his work connect with the spirit of the spire’s unstoppable propulsion, Delaunay levitates us with him into the atmosphere above the cathedral - so close to the wind-whittled length of the ethereal spire, it becomes more substantial than the stone structure on which it sits. In Delaunay’s stirring vision, the spire becomes a conduit of energy, a cable that links us with the power of something beyond – one we can hold onto in our memories until its physical echo is eventually restored.

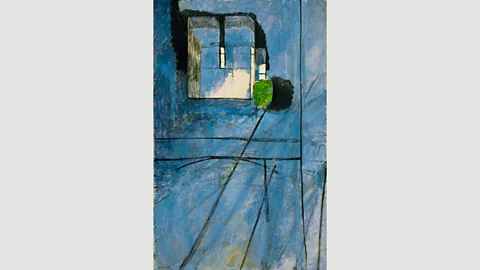

Henri Matisse, View of Notre-Dame, 1914

Alamy

AlamyIt wasn’t the first time Matisse painted Notre-Dame. Years earlier, in 1902, he’d stared across the River Seine from the very same spot on the Quai Saint-Michel and captured the cathedral’s mystique in vivid reds and violets with a poetry that anticipated the artist’s imminent turn to Fauvism. But this time was different. Almost as quickly as Matisse had constructed the contours of his scene, he blotted it out. Not entirely, but mostly, with a veil of blue paint, retaining only a cut-out window of the towers, a splotch of scrubby green, and a handful of half-hints of the occluded world he’d otherwise erased. Neither figurative nor abstract, but havering between the world of the body and that of the soul, the work was daringly modern in its bold experimentation – like the snapshot of a feeling rather than a place. Too daring. He kept the remarkable painting to himself, like a superstitious foreboding, and refused to exhibit it for the rest of his life.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.