Is this a photo or a painting?

Aung Thu/AFP/Getty Images

Aung Thu/AFP/Getty ImagesAn image snapped in Myanmar shows festival goers shielding themselves against cascading sparks. Kelly Grovier examines the incandescent appeal of the firework.

For more than 14 centuries, human beings have hurled against the black canvas of the night sky fleeting scrawls of fiery brilliance. In stark contrast to other forms of visual art, such as painting, drawing, and sculpture (which aspire to a physical permanence that outlives their creator), fireworks rely on our fascination instead with impermanence. Since what comprises each of us is nothing more than cosmic dust – the remnants of a bigger bang – is it any wonder that we should be so attuned to the conjoined beauty and violence of a firework’s ignition and display?

Aung Thu/AFP/Getty Images

Aung Thu/AFP/Getty ImagesThe existential question occurred to me this week after a terrifying photo, taken during the Tazaungdaing Lighting Festival at Taunggyi in Myanmar’s northeastern Shan State, began circulating in social media. As part of the festival, balloons with hundreds of homemade fireworks woven into their frames are sent soaring into the night sky, showering down cascades of sparks. The photo captures the moment when festival goers were forced to shield themselves from a dangerous downpour of fire after a low-floating basket suddenly exploded over their heads. In spite of the well-publicised risks of attending such displays (four people died and at least 12 people were injured in accidents at the same festival in 2014), spectators remain incorrigibly compelled to their lethal allure.

Wikimedia

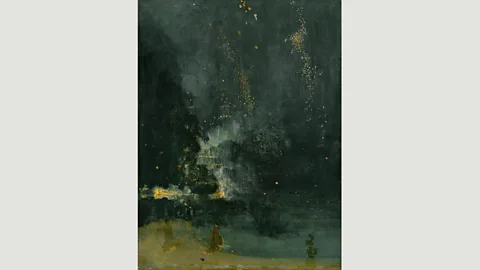

WikimediaNo artist understood the profundity of fireworks better than the 19th-Century American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler. A frequent attendee at the nightly displays in the popular pleasure gardens of London in the 1870s, Whistler glimpsed in the soaring surges of uncontainable colour against unprimed darkness not merely a subject suitable for painting, however difficult to harness, but a licence to reinvent the medium itself. In essence, his controversial canvas Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket, painted around 1875 (the last in a seminal series of so-called ‘nocturnes’), attempts to capture not so much the retinal appearance of fireworks fizzling into fog as the intense feeling experienced by someone watching them flash into incandescence and disappear forever.

Though recognised today as a significant stride toward non-representational art, Whistler’s murky smudges in Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket left him open to fierce attacks from those who believed the painting was an aesthetic assault. Accused by the celebrated critic John Ruskin of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”, Whistler was forced to defend himself by suing Ruskin for defamation – a move somewhat sabotaged by officials who presented the painting to the court upside down. As with this week's photo from Myanmar, Whistler's daring painting took observers to the very edge of what is safe for the soul to see.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.