Is this the painting that can mean anything?

In the 500 years since Leonardo da Vinci painted his Mona Lisa, the image has taken on different roles for viewers. Kelly Grovier looks at its latest incarnation.

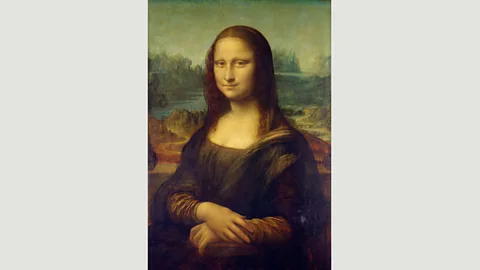

Can art mean anything we want it to? A cameo appearance made this week by the Mona Lisa during a march through the streets of Poland to protest proposed legislation that would ban abortion in every circumstance (even when the mother’s life is in danger), raises an intriguing cultural question: are some works so elastic and so ambiguous they can express whatever messages we wish to attach to them? Rather than the jostling placards emblazoned with the slogan “Moja macica, mój wybór” (“My uterus, my choice”) that many of their fellow protesters carried, a pair of activists are seen hoisting into drizzly air a larger-than-life-size reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous portrait of the Florentine woman Lisa del Giocondo – as if her patiently folded arms and indecipherable smile could more eloquently express their dissent.

AP Photo/Alik Keplicz

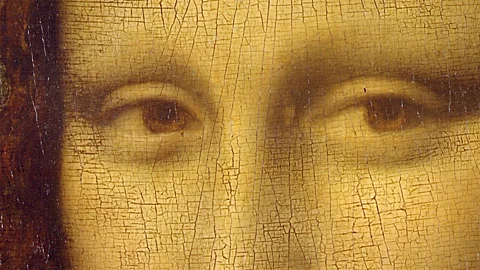

AP Photo/Alik KepliczWe now know that the participants in the nationwide ‘Black Monday’ strike have succeeded in persuading lawmakers to reverse course and to abandon their highly contentious legislation. But was Lisa misappropriated by protesters, made to stand for ideas and ideals to which she (and the artist who painted her) may never have subscribed? Examining the painting through the narrowest of historical lenses, one could peevishly query the wisdom of recruiting her as a poster child. Many scholars now suspect that Lisa was, herself, likely pregnant when she sat for da Vinci’s portrait. In 2006, a team of researchers using 3D imaging on the likeness revealed the time-worn presence of a gauzy garment known as a guarnello – a kind of veil worn by Italian Renaissance women who were expecting.

Wikipedia

WikipediaBut great art transcends the conditions of its making and in the half millennium since the portrait was created, the Mona Lisa has woven herself delicately but indelibly into the popular imagination. To look through the archives of 16th-Century Florence for evidence of contemporary attitudes to abortion to determine whether Lisa would have approved of the objectives of the Black Monday strike would risk obtusely demoting da Vinci’s masterpiece to an ephemeral caption – a footnote tethered to a single time and place. (For those keen to know: it’s unlikely that Lisa or her generation would have regarded the procedure as an illegal offence. “The law codes of Florence,” in this period, according to Nicholas Terpstra, professor of history at the University of Toronto, “make no mention of abortion, and certainly do not cast it as a punishable form of homicide”.)

The appropriation of the Mona Lisa by Polish activists this week merely reaffirms her status as among the most inexhaustible, indomitable, and endlessly convertible of icons. Her ability to survive kidnapping (the painting was stolen in 1911 and was missing for two years), repeated parody (Marcel Duchamp famously affixed a mischievous moustache on her in 1919 above the initials “LHOOQ”, which form the phrase “she’s got a hot arse”, when read out in French), and celebrity-scale scrutiny for centuries, has given her countenance a mysterious cartography – a map that can lead us anywhere we want to go.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.