'Image manipulation has always been around': 10 early photographic 'fakes' that trick the eye

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

Courtesy of the RijksmuseumHave photographs ever really told the truth? One hundred and fifty years before today's controversial AI chatbots and deep fakes, photographers created remarkable image manipulations. Here are 10 images from the 19th and 20th Centuries that tricked the viewer.

Image manipulation and the unreliability of the visual media we consume is causing widespread concern. Elon Musk's controversial AI chatbot, Grok, which caused uproar after it was used to alter images of people so that they appear stripped of their clothing, is the latest in a series of sophisticated digital imaging tools that have falsified photographs and, in some cases, caused serious harm. In January, following widespread criticism, this function was disabled for most users, and the European Commission launched an investigation into its use.

It will take more than this, however, to restore our faith in the photographic image. Since the early days of Photoshop in the 1990s, developments in image fakery have seen us looking at photographs with rising suspicion. But the Rijksmuseum's latest photography exhibition asks a pertinent question: Have photographs ever told the truth?

Focusing on images taken between 1860 and 1940, Fake! Early Photo Collages and Photomontages from the Rijksmuseum Collection makes the case that image fakery is far from a recent phenomenon and, when used wisely, can even be a force for good. From collages created with scissors and glue to clever deceptions fabricated under cover of darkness in their developing rooms, photographers have always enjoyed fooling their audiences. "Image manipulation has been around as long as photography itself," the exhibition’s curator, Hans Rooseboom, tells the BBC. "It’s part of the whole history of photography." Here are 10 images from the exhibition that tell the story of the early days of photographic trickery.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum1. Daydream (c 1870–1890), anonymous

Two realities collide in this 19th-Century carte de visite that was most likely purchased to be collected and traded. Cartes de visite were small mass-produced prints mounted on card, and were very popular in the Victorian era. In this one we see the present: a woman and her partner both with the tools of their trades; and an imagined future: her daydream of becoming a mother. The image, explains Rooseboom, was "a darkroom trick", achieved by shielding part of the photographic paper from the light and then adding a second negative to it later. Such images took photography into a new dimension, suggesting the innermost thoughts of their subjects, and paving the way for the comic strips of the future with their speech bubbles and thought clouds.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

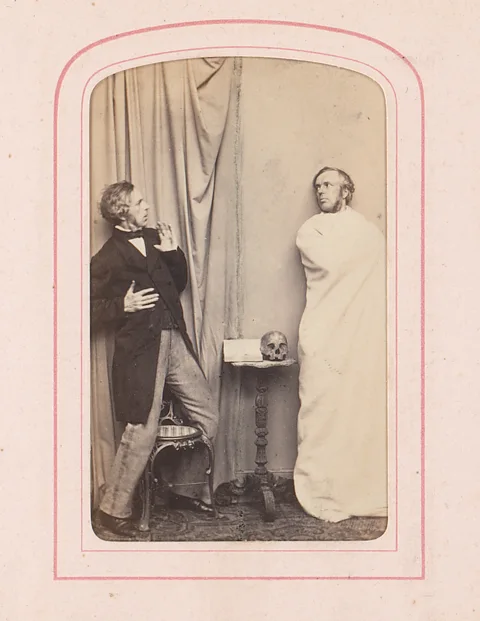

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum2. Man startled by his own reflection (c 1870–1880), Leonard de Koningh

In this comical memento mori, where a man comes face to face with his ghost, the painter and photographer Leonard de Koningh exposed just half of the photographic plate, then had the subject adopt a different pose before exposing the other half. Photography might have been a relatively new art, but the transition between the two images is imperceptible. "It's like a magician," marvels Rooseboom. "You know you are being tricked, but you don't know how the photographer does it." Quoting Oscar Gustave Rejlander, a trailblazer for this type of composite printing, the photographer Robert Sobieszek (1943-2005) stated: "This manner of working led not to falsehood but to truth. An image made by a single negative [claimed Rejlander] 'is not true, nor will it ever be so – the focus cannot be everywhere'."

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

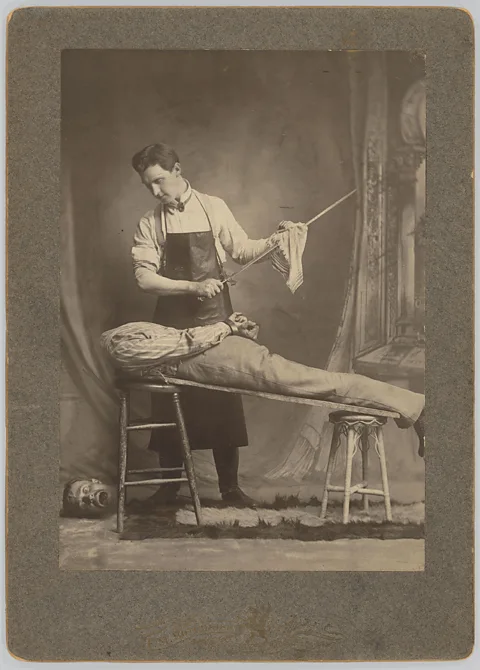

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum3. Decapitation (c 1880–1900), FM Hotchkiss

"We still expect photography to bring the truth, but this idea only really emerged from the illustrated magazines of the 1930s in order to inform readers how things worked elsewhere in the world," says Rooseboom. Until then, the creative freedom to alter the image was unchallenged. "Anything possible would be tried out and produced," he says. "There was no ethical restraint on producing non-realistic images. No-one would forbid you from doing this." Removing and moving someone's head, for example, presented the photographer with a pleasing puzzle. In the case of this cabinet card – a style of print mounted on card had taken over from the smaller carte de visite by the 1880s – with its black humour, the creative mission was highly successful. Only the positioning of the curtain, that would have concealed the original head, and some light retouching visible under a microscope, offer clues to how the photographer created the deception.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum4. Photomontage of a man pushing a wheelbarrow containing a head(c 1900–1910), anonymous

This photomontage, created from two negatives, was found in a French photo album, and featured in the science magazine La Nature. Here, the displaced head illusion goes a step further as the photographer plays with scale, prefiguring the Surrealist movement which gathered pace as the century unrolled, disrupting conventional shapes and sizes to create confusing, dreamlike scenes. The open doorway provides a conveniently plain, dark background in which to smuggle in the cut-and-pasted portion before re-photographing the image as a whole. Some of these images were most likely purchased as portraits to show others, to see their look of surprise. "It's hard to see where the trick starts and ends," says Rooseboom. "This is showing off. Something is unbelievable, impossible, it's improbable, but still it's there in a photographic image which suggests we see a real scene that really unfolded in front of the camera."

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum5.Taking our Geese to market (1909), Martin Post Card Company

The trend for playing with images of impossible proportions spawned a genre known as "Exaggerations" or "Tall Tales". This US photograph was printed during the "Golden Age" of picture postcards, shortly after the US decreed that messages could be written on the address side of the card. We see again the pioneering role photo manipulation plays in artistic developments such as Surrealism, but the use of scale here is also a marketing ploy to create myths about the agricultural superiority of a region. In this case, it's the celebrated stuffed geese of Watertown, Wisconsin. Elsewhere in the show, Nebraska boasts about its bountiful produce with an ear of corn the length of a horse-drawn carriage. As US author and folklorist Roger Welsch noted in Tall Tale Postcards (1976): "Photography brought into being visual effects that tall-tale tellers through the centuries had seen only in their fertile imaginations."

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum6.Car floating above Mulberry Bend Park, New York (1908), Theodor Eismann

Fake photographs activated the imagination, presenting imagined possibilities yet to come. This example of a toekomstbeeld (vision of the future) envisages a world where cars could fly. Elsewhere in the exhibition we see futuristic cityscapes: town centres transformed by sky rails and zeppelins thanks to some deft copy and pasting, and skyborne visitors floating over Boston, Hamburg and The Hague in scenes reminiscent of Mary Poppins. Eismann's New York photomontage [above] now features colour but is no more truthful, its limited range of inks added during the printing process at the whim of the designer.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

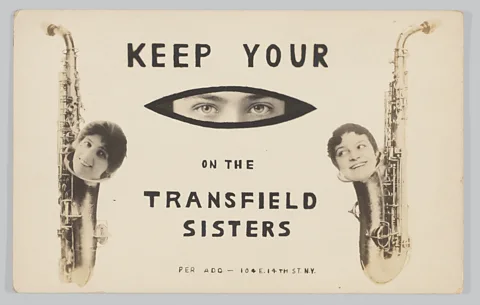

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum7. Advertisement for the Transfield Sisters (c 1904-1918), anonymous

As the 20th Century dawned, photography assumed a growing role in advertising, attracting attention with playful designs such as this early advert for the vaudeville act the Transfield Sisters. Photomontages used different-sized photographs, shot at a range of angles, which created, "a dynamic visual language, reflecting an era of rapid change". The marriage of advertising and photography brought about "an interplay between fiction and facts", explains Rooseboom. "This play between what you can believe and what you can't believe, what’s possible and impossible, that's the little game they are playing in all these images."

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum8.Collision between a car and a steamroller (1915), Alfred Stanley Johnson Jr

We've come to think of photo trickery as something sinister, but in his research on its use in early photography, Rooseboom says he was surprised to find that "three-quarters of all the images were made for fun". In this photomontage by Alfred Stanley Johnson Jr, the clever placement of a series of individual − sometimes overlapping − images provides a humorous snapshot in time. The unusually dynamic, action-filled scene features flying coattails and frilly bloomers as the passengers of a car are catapulted through the air, inviting a before-and-after narrative in the mind of the viewer. "Many photomontages obviously depict impossible situations," states a text at the exhibition. "The intention was not to mislead, but rather to entertain the viewer."

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum9. Photo collage (1929), Albert Huyot

The cutting up of images and rearranging them on paper with glue was once a popular pastime. People made celebrity photo quizzes, sometimes featuring just a nose or a pair of eyes; and the photographed faces of friends and family were superimposed onto drawings for comic effect. Photo collages were also undertaken by established artists. In this piece, which is influenced by Dadaism and Cubism, French artist Albert Huyot manipulates fragments of photographic images into surprising new artistic forms. More intricate photographic artworks can be seen in the show on the pages of the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy's seminal book Painting, Photography, Film (1925). In it he argues that photography is not just about recording reality. Instead, it should explore the visual language unique to its medium.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

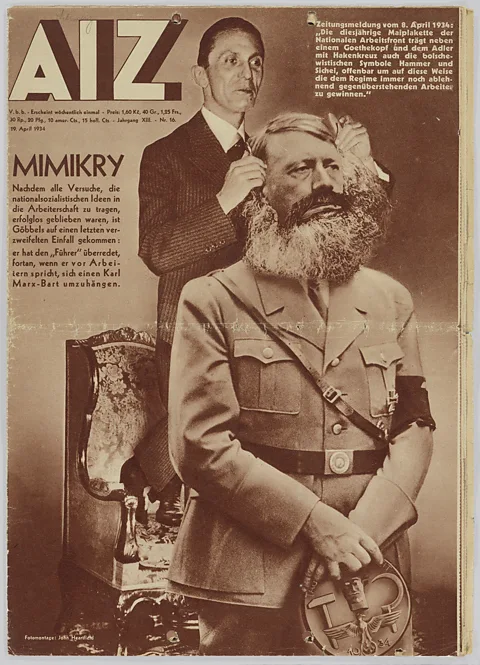

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum10.Mimicry (Joseph Goebbels disguising Hitler as Karl Marx to placate the workers) (1934),John Heartfield

Sometimes, in a surprising twist, photographic trickery was a tool for conveying a perceived truth. Anti-Nazi campaigner Helmut Herzfeld, who changed his name to the anglicised John Heartfield in protest against Hitler's regime, created over 200 handcrafted political photomontages for the leftist AIZ publication, many seeking to expose the hidden dangers of the Nazi dictatorship and the lies it disseminated. Mimicry depicts Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, disguising Hitler as the 19th-Century revolutionary communist Karl Marx. The artist is warning the working classes not to be fooled by Hitler's promises that he genuinely supports workers' rights. Such work is comparable with political memes today that aim to speak truth to power. Image manipulation can both mislead us and help us find our way.

Fake! Early Photo Collages and Photomontages from the Rijksmuseum Collection is at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam until 25 May 2026.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.