'There was cruelty': How America's Next Top Model became a TV horror show

Getty Images

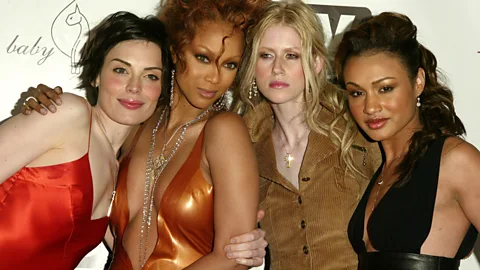

Getty ImagesFor 15 years, the modelling contest hosted by Tyra Banks was a global phenomenon. But it also featured many shocking and questionable moments – and now a new Netflix docuseries is set to reflect on its controversies.

Ask any fan of the seminal supermodel competition show, America's Next Top Model (ANTM), for its most unforgettable moment, and they'll likely give you the same answer: the episode when host Tyra Banks screamed with rage at a contestant who she believed wasn't taking it seriously enough.

"I was rooting for you. We were all rooting for you! How dare you! Learn something from this!" Banks yells at aspiring model Tiffany Richardson, who Banks had just evicted from the contest, in a clip that has long been a famous meme. As the most indelible moment from the series, which ran from 2003 for a remarkable 24 "cycles" (or seasons), it's the obvious place to begin for a new Netflix documentary series examining the show, especially as the clip really resurfaced again on social media during the pandemic in 2020. It led viewers to dig out other controversial scenes from the show's back catalogue, and unsurprisingly, reassessed through a 2020s lens, they had not aged well – Banks even wrote on Twitter at the time: "Been seeing the posts about the insensitivity of some past ANTM moments and I agree with you. Looking back, those were some really off choices."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesContinuing this retroactive exposé of the show, last year saw the release of a podcast, Curse of: America's Next Top Model, which is now followed by a three-part Netflix series Reality Check: Inside America's Next Top Model. Premiering next week, it catalogues a whole host of controversial events which occurred both on and off screen, at the expense of the young women who had signed up for a show that would supposedly transform their lives for the better. "There were cruel aspects of ANTM," says Danielle Lindemann, author of True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us. "But, for better or worse, it is part of the cultural zeitgeist."

The documentary speaks to a series of former contestants of the show, as well as to Banks and her co-stars, and asks: how did ANTM become so toxic?

How it all began

The series started, as many things do, with noble intentions. In 2003, having made a name for herself as a top supermodel, Banks turned her attention to TV. Her idea – developed alongside producer Ken Mok – was a reality TV show that aimed to democratise the fashion industry by plucking a girl from obscurity, training her up and launching her as the next big deal in the modelling world.

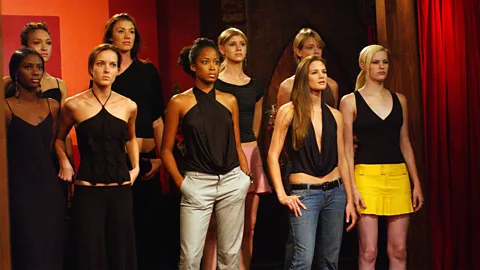

It was indeed a pioneering TV show, in a world where reality TV was in its relative infancy. Fly-on-the-wall series Big Brother had started just four years earlier, while competition shows Survivor and Fear Factor were the other reality TV shows of the moment. ANTM was an amalgamation of both these forms – a high-stakes contest, where contestants would battle it out each week on set during glamorous themed photoshoots, which also offered a behind-the-scenes look at the lives of the young women when they returned back to their shared apartment.

It was a ratings hit, and spread throughout the world, picking up an estimated 100 million viewers across 170 countries. At the time, the show was applauded for its progressiveness in putting a black woman at the heart of a TV juggernaut, alongside two charismatic gay men, runway coach turned judge Miss J Alexander and creative director Jay Manuel. Between the three of them, as well as the contestants, it offered the kind of diverse representation that was otherwise unheard of on TV back in the early '00s.

"This was a show filled with people of colour, queer people, and at least some different body types," Lindemann tells the BBC. "ANTM helped to show us how successful an extremely diverse reality competition could be. Over a decade before same-sex marriage was legalised in the US, ANTM was quietly bringing queer representation to a massive audience. One could argue that it helped to pave the way for shows like RuPaul's Drag Race."

On the flipside, ANTM, while claiming to support women breaking into a famously elitist industry, ended up perpetuating some of the very prejudices it wanted to challenge, and became increasingly toxic as the seasons progressed.

Alamy

AlamyNot only did the judges' feedback become more personally offensive – with the trio pointing out models' "bloated" bellies or criticising the size of their behinds – but the situations in which they placed the contestants appeared to become calculated to humiliate them in the name of "good TV".

The show's repeated controversies

The centrepoint of each episode was the photoshoot, where the girls were given a makeover and challenged to take the winning photo of the day. These quickly veered into eyebrow-raising – and then alarmingly insensitive – territory. The most infamous of them all, perhaps, is the "switching ethnicities" photoshoot that took place in season four (2005) in which one model was painted in blackface, though many people forget that the same concept was repeated in season 13 (2009). Alongside this, there was the homeless-themed photoshoot, in which real-life homeless people were used as extras; a shoot mocking model stereotypes, which saw one model asked to pose throwing up in the toilet – with fake vomit on her – to convey bulimia; and a challenge in which contestants had to pretend to be murder victims in "crime scene" set-ups. One participant in the latter, Dionne Walters, claims in the Netflix docuseries that people in production made her pretend she had been shot despite knowing that her mother had been previously shot and paralysed.

In Reality Check, Banks contests that, when it comes to these offensive shoots, "you guys [the audience] were demanding it!" although she concedes that looking at the show through a present-day lens, "it's an issue, and I understand why".

Other serious incidents that the documentary recounts include one woman who describes a situation where she was "blacked out" from being drunk, and filmed by the show having sex with a man who wasn't her boyfriend, before then being made to phone her partner to confess on camera. And another who complained of being sexually harassed by a male model – an incident shown in Reality Check via footage from ANTM – was later chastised by Banks for speaking out. Banks says of this incident: "None of us knew. Network executives didn't know. And I did the best I could at that time. But she deserved more."

The BBC approached ATNM's lead production company 10x10 entertainment for comment on allegations included in the Netflix documentary series, but they did not respond.

The show was also regarded as one of the pioneers of the reality TV technique known as the "villain edit", in which particular contestants are harshly edited to create a bad impression of them – something that multiple ANTM contestants allege they were subject to in the documentary. "It wasn't a model show, it was a new way of making TV shows," says model Ebony Haith in the documentary, describing how she woke up to the fact that the series may have ulterior motives beyond promoting new modelling talent.

More like this:

• 10 of the best TV shows to watch this February

• The surprising depths of the Real Housewives

• The power of Stephen King's most disturbing novel

When it comes to reality TV, there have certainly been more extreme shows, particularly during the genre's Wild West era in the Noughties – see 2004's plastic surgery makeover series The Swan, to take one example. But in terms of how long America's Next Top Model ran and the sheer number of missteps it made, it could be argued that few have had so pernicious an impact on popular culture. When the show initially ended in 2015 (before being rebooted for two more seasons), the New York Times asked if we should now be celebrating "the end of a major chapter in the dehumanizing era of reality TV". Just last year, Otegha Uwagba reflected in Grazia that the show's "secret sauce was the ritual humiliation and exploitation of often deeply vulnerable women".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome ANTM contestants have also argued the show failed to prepare them to go back into the world after their sudden infamy. In Reality Check, season two participant Shandi Sullivan recalls being called slurs while walking down the street afterwards while another show graduate, season six's Dani Evans – who was famously asked to have the gap in her teeth closed on the show – suggests that her appearance on ANTM actually closed doors for her in the industry, as designers "didn't want a reality star walking their shows".

The show's co-creator and executive producer Ken Mok admits that girls who appeared on the show had to deal with "a stigma" when finally entering the model world. "That doesn't surprise me," says fashion podcaster and presenter, Belinda Naylor. "There's a snobbery about reality TV shows, which only adds to how hard it's always been to get work in the fashion world".

Looking back on it with a 2025 lens

It will be interesting to see how the perception of the show is shifted yet again by the airing of the Netflix series. Banks takes the chance in it to express some regret for what went on: "I knew I went too far. I lost it…" she says of her infamous moment of anger. Mok, too, is remorseful: "I take full responsibility for that shoot," he says of the infamous "crime scene"-themed challenge. "That was a mistake. I look back now and I think it was a celebration of, like, violence. It was crazy. That one I look back on and am like, 'you were an idiot'."

Not everyone agrees with relitigating the show, though. Season one winner Adrianne Curry refused to participate in Reality Check and has spoken out against it, suggesting it is futile to judge decades-old shows according to today's standards. "I think people psychoanalysing it over 20 years later with a woke lens is absurd," she wrote on social media.

But it's important even for older shows to have a reckoning, says Lindemann, and to acknowledge its impact, good and bad, on society. "I do think it's valid to say, 'Knowing what I know now, viewing this cultural work doesn't give me the same pleasure anymore, because I recognise its harms," she says. "Because you have direct knowledge that it harmed the people who participated in it and/or it contributed to a broader social harm like sexism or racism. This is not to say that everyone who participated in a problematic show is an absolute monster – just that we have a different lens for viewing it now. That said, there are some problematic aspects of the show that should have gotten the side-eye from us, even at the time."

"ANTM was very much a product of its time," she adds. "To me, it's always been very much a reflectionof what the modelling industry was like at the time – or at least a funhouse mirror reflection.”

Reality Check: Inside America's Next Top Model is released on Netflix on 16 February.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.