'It's almost like a weapon': How the blonde bombshell has symbolised desire and danger

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFrom the American sweetheart to the platinum ice queen, and Jean Harlow to Sydney Sweeney, the blonde bombshell has been a multi-faceted - and controversial - figure in popular culture.

Women's hair has long been endowed with an intoxicating power, from the snake-headed Medusa of Greek mythology, whose arresting appearance turned victims to stone, to Victorian paintings of wavy-haired temptresses and gothic predators, with wild, untamed locks. Embodied by heavily made-up femme fatales such as Theda Bara and Louise Glaum, the predominantly dark-haired "vamp" made her way into the early films of the 1920s, until the advent of hair bleach saw her elbowed out by a bold new cultural icon: the platinum blonde, her immaculate coiffure glowing from the monochrome film.

Alamy

AlamyA new book, British Blonde: Women, Desire and the Image in Postwar Britain, by cultural historian Lynda Nead, examines how the bleached blonde became a complex symbol of both desirability and danger, from her US origins, most famously personified by Marilyn Monroe, to her diverse British incarnations such as Diana Dors and Barbara Windsor. "Blondeness seemed to be so significant, it wasn't just a little detail that you could ignore, it seemed to me what was defining these familiar faces and images," Nead, who is Professor of History of Art at the Courtauld Institute of Art, tells the BBC.

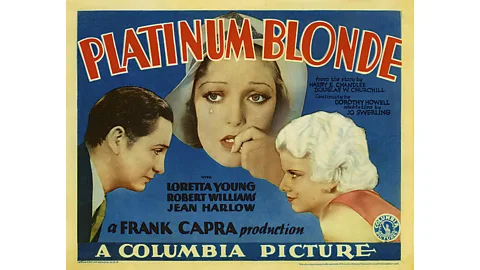

Western culture, she says, has built a whole mythology around female blondeness − from religious iconography and fairy tales, to art and advertising − that has told specific stories about what it means to be blonde. In cinema's early years, comedies such as Platinum Blonde (1931) and Bombshell (1933), starring Jean Harlow, embedded concepts of the dazzling, devastatingly beautiful blonde into the cultural vernacular. "The idea that you're a bombshell, it's almost like a weapon," says Nead. "On the one hand, it is this kind of ideal, but at the same time, it's also threatening."

Before Harlow, there was another − more natural-looking − blonde on the scene: Mary Pickford, whose amber curls helped earn her the moniker of "America's Sweetheart". But while Pickford played the guileless girl waiting to be rescued, Harlow's peroxide blonde was more empowered, paving the way for fair-haired femme fatales of 1940s film noir such as Veronica Lake and Barbara Stanwyck, who played alluring but devious women who used their charm and wits to manipulate men.

Alamy

AlamyBlonde Ice (1948), starring Leslie Brooks as a cold-hearted adulterer, fraudster and murderer, would capitalise on the popularity of the "blonde ice queen" trope − the protagonist's halo of golden hair at odds with her dark intentions. It was a construct revisited in the thriller Basic Instinct (1992), where Sharon Stone plays the calculating Catherine Tramell, the suspect in a murder case who succeeds in seducing her interrogator.

Blonde hair, which tends to darken with age, suggests a radiance and a childlike innocence that facilitates the femme fatale's deception. In The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), for example, Cora Smith (played by Lana Turner) lures her lover into helping murder her husband, her flawless white wardrobe and baby-blonde hair disguising the scheming character within.

More like this:

• How Gwyneth Paltrow became a divisive icon

• Why the Virgin Queen never married

• The US statue at the heart of a culture war

"Blondeness is something that's been projected as an ideal within Western terms of beauty", says Nead, which, in the context of ideologies of white racial superiority, is "deeply problematic". Only this month, the appearance of blonde actress Sydney Sweeney in an advert for denim brand American Eagle which made a pun on genes – by saying she "had great jeans" – was criticised by some for allegedly using language associated with eugenics, the discredited theory that the human race could be improved by selective breeding. American Eagle refuted such claims, saying that the tagline "is and always was about the jeans. Her jeans. Her story".

Despite these disturbing undertones, in post-war Britain, blonde hair dye was seen by many white women as a passport to a glamorous, material world that felt empowering after years of austerity. Consumerist culture crossed the Atlantic, with adverts for Clairol hair dye emphasising the blonde's power over men and inviting women to "switch to bewitch" with slogans such as "If I've only one life, let me live it as a blonde".

Purity and artifice

Yet bottle blondes had to work hard to maintain their striking look. The relentless regime of redyeing was part of the intriguing duality of blonde hair, which denoted "both absolute purity and utter artifice", writes Nead in the book. "Ambiguity lies at the heart of the British blonde," she continues. "A surface of perfection conceals, as its shadow counterpart, the forbidden and the dangerous, made visible in the dark roots of dyed blonde, which expose the breach in the feminine masquerade, in the screen of perfect femininity."

Alamy

AlamyFor British blondes, such as actress and sex symbol Diana Dors (1931-1984), it was tough walking in Monroe's shadow. Though they were instrumental in defining their own identities, they were, remarks Nead in the book, fated to be "a runner up to the American blonde". Subjected to the fault lines of the British class system, they took noticeably different forms. Dors, for example, was more brassy than her US counterparts. "She carries blondeness almost to the point of caricature," reported the Daily Mail in 1956.

Her contemporary, cheeky Cockney Barbara Windsor, best known for the bawdy Carry On films, embodied a more ditsy, bubbly blonde. The same newspaper (quoted in the book) described her as a "striking mixture of faux innocence and overt sexuality". This persona is encapsulated in a publicity image for the comedy film Crooks in Cloisters (1964), featuring a wide-eyed Windsor, dressed in a babydoll negligée and fluffy mules, her white-blonde hair piled up in a frothy beehive.

Cinema's love affair with the so-called "dumb blonde" has not prevented it from challenging the stereotype. At the beginning of Legally Blonde (2001), starring Reese Witherspoon as the Barbie-like Elle Woods, her high-reaching boyfriend ends their relationship due to his low expectations of her. "If I'm going to be a senator, I need to marry a Jackie, not a Marilyn," he explains. However his judgement is proved entirely wrong, as Elle is accepted into, and flourishes, at law school.

Alamy

AlamyYet many of Marilyn Monroe's roles also hint at her hidden depths, revealing her sensitivity and intelligence. In Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), Esmond Sr, the future father-in-law to the showgirl Lorelei Lee, played by Monroe, is surprised by the quick-thinking blonde. "Say, they told me you were stupid. You don't sound stupid to me!" he exclaims. "l can be smart when it's important," she responds. "But most men don't like it."

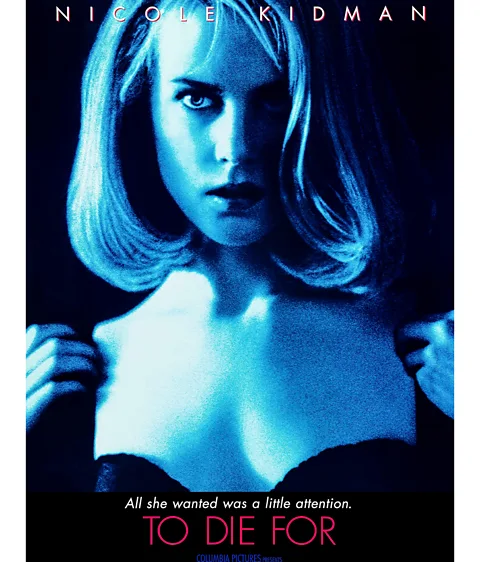

It's perhaps because blondes are so often underestimated that they make such perfect femmes fatales. In To Die For (1995), Nicole Kidman stars as Suzanne Stone, an ambitious blonde weather presenter. Here, her feigned naivety and winsome appearance help conceal her ruthless self-advancement, but when the truth is out, headlines such as "blonde temptress" issue a warning. Ultimately, culture appears to side with the blonde, who we patronise at our peril. As Dolly Parton sang in 1967: "This dumb blonde ain't nobody's fool."

British Blonde: Women, Desire and the Image in Postwar Britain by Lynda Nead is published by the Paul Mellon Centre for British Art and available from 9 September.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.