The amazing photos of London’s apocalyptic sky

Peter Macdiarmid/LNP

Peter Macdiarmid/LNPAfter Hurricane Ophelia left a strange haziness in parts of the UK this week, Kelly Grovier looks at how the orange atmosphere has echoes in Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

In the Frame

Each week Kelly Grovier takes a photo from the news and likens it to a great work of art.

It looked more like a cinematic special effect than an actual atmospheric phenomenon: Saharan dust, swept up by Hurricane Ophelia as the storm barrelled up the Atlantic, choked the southern English sky earlier this week in a saffron scarf of mist and suspended desert minerals. Silhouetted against a sepia sunset, worldly objects suddenly darkened into something smoky and strange, surreal as solid shadows.

Shared widely across social media, photos of the mustard-tinted air were frequently likened to the alien gloam that unsettles so many dystopian thrillers. “Wow,” one Twitter user quipped, “this Blade Runner promo looks so realistic”. One especially powerful image of the aerial event, snapped over the shoulder of British sculptor Ivor-Roberts Jones’s hulking bronze statue of Prime Minister Winston Churchill in Parliament Square, seemed to fix London forever in the smoulder of a hazy dream.

Peter Macdiarmid/LNP

Peter Macdiarmid/LNPAlchemised into a heavy shade, Churchill stares at Big Ben, whose hands and face are obscured by scaffolding, as an inscrutable cinnamon sky embers above. That affecting contrast of solitary figure framed against burning air has invigorated the imagination of countless artists. Vincent van Gogh seized upon it for his famous Sower at Sunset (1888), which sets a shadowy sharecropper against the dissipating heat of a shimmering sundown.

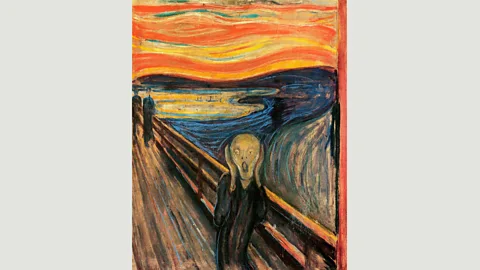

But perhaps the most compelling comparison that can be drawn between a stark figure frozen beneath an apocalyptic sky and a work from the history of art is to that sustainable masterpiece of psychological climate change, Edvard Munch’s The Scream, painted in 1893, five years after Van Gogh’s soulful sower. So nightmarish is the liquescent skull that shrieks beneath the striations of a tortured Halloween sky in Munch’s famous work, one readily assumes the image is entirely untethered to physical reality and has been summoned instead expressionistically from the anguished corners of the artist’s soul.

Edvard Munch/public domain

Edvard Munch/public domainBut Munch would later insist that the work is faithful to what he actually witnessed on a stroll in the hills above the Norwegian capital the year before he created the image out of a mixture of oil paint, tempera, pastels and crayon on cardboard. “I was walking along the road with two friends,” the artist recorded in his diary in January 1892, “the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red … there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.”

What might account for the eerie effect that Munch so hypnotically portrays? In 2007, a team of researchers from Texas State University proposed that Munch’s painting is, in fact, an accurate representation of the type of blood-streaked skies that had been observed as far north as Norway in the months following the eruption of the volcanic Indonesian island of Krakatoa in August 1883. The Scream, according to the team’s conclusions, is likely a vivid recollection of those vampiric sunsets, created by a “cloud of volcanic aerosols”, that Munch himself would have witnessed as a young man a decade before he painted his work.

Placed alongside this week’s photo from an otherworldly London, Munch’s spectral portrait, likewise shrouded in the alluvial light of a distant cataclysm, reminds us how vaporous the distinction can seem between the atmospheres we see outside us and those mysterious skies that shift within.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to ourFacebookpage or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story,sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.