What will be the next Walking Dead?

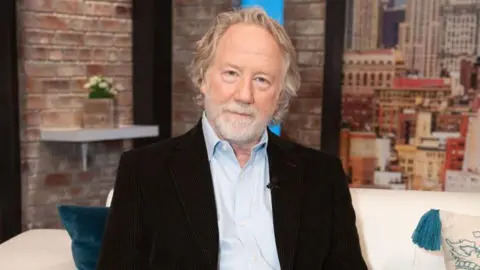

Universal Studios

Universal StudiosThe zombie genre may shuffle into some very different dramatic territory, including some more humane considerations of the undead, says horror expert Roger Luckhurst.

The Walking Dead returns to US screens on14 February with a typically blood-soaked instalment – the perfect way to celebrate Valentine's Day. But in case the show isn't enough to satisfy your desire for grisly tales of the undead, you might be wondering where to go next for your zombie fix.

This is a good moment to reflect that The Walking Dead remains very loyal to the cinema model of the zombie apocalypse as invented in the films of George Romero, from Night of the Living Dead (1968) onwards. There are direct lines of connection, of course: the key producer, director and special effects person on The Walking Dead is Greg Nicotero, who first made his mark working with Romero on The Day of the Dead (1985). The TV series hasn’t messed much with the Romero formula.

Fans get very fixed on the ‘rules’ of the genre. There was outrage when Danny Boyle’s film 28 Days Later… (2002) introduced zombies that no longer shuffled but ran around in murderous rage. There were further doubts this was a proper zombie film, since the outbreak was explained as a virus contagion. How times have changed: this is now the standard back-story for most zombie disaster tales.

So we can conclude that the zombie is never particularly fixed in a set of conventions, and is instead an incredibly mobile and malleable metaphor. And actually, just watching The Walking Dead disguises the fact that there have recently been some very striking changes in cultural uses of the zombie.

AF Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

AF Archive/Alamy Stock PhotoFor Rick Grimes and his crew on The Walking Dead, zombies are merely anonymous hordes, there to be dispatched. They are rarely individualised. Rick perhaps shows a little pity in the very first episode of the entire series, but after that it is all about learning to live without sentiment. They are the implacable enemy.

We want brains

But just in the last few years, something amazing has happened: the zombies have started acquiring the stirrings of consciousness. We are beginning to hear the experience of zombification from their side of the fence. There were perhaps some stirrings of this in Romero’s late addition to his series of films, Land of the Dead (2005), in which the zombies seem to find a leader in Big Daddy, who leads them with some intelligence towards the overthrow of their human oppressors. But Romero has not pursued this idea in his most recent additions to his series.

Others, however, have really developed this idea. SG Browne’s novel, Breathers: A Zombie’s Lament (2009) is a gruesomely funny account of the laborious process of waking up dead and learning the ropes of one’s new dispensation. There is quite a lot of etiquette to grasp, particularly around eating your parents.

Isaac Marion published the novel Warm Bodies in 2010, a clever re-telling of Romeo and Juliet as a romance between zombie ‘R’, who cannot quite recall his full name, and the love of his life (or death), a human survivor with an unforgiving zombie-killing dad.

Jonathan Levine made it into a successful zom-rom-com film in 2013, worth seeing for the dazzling opening minutes alone, as R shuffles aimlessly around the airport terminal where he died, dimly haunted by fragments of memory from his prior existence. Warm Bodiesis out to show that only love can breathe life back into deadened teen existence.

The CW

The CWAlso in 2010, Chris Roberson and Michael Allred began the iZombie series for Vertigo Comics. It centres on Gwen, a young woman who becomes zombified yet can pass as a human if she can get hold of a small meal of human brains once a month (easy enough with a job in a morgue). Eating brains, however, comes with the impressions, memories and experiences of those human beings being tasted. The comic is an oddly impressive reflection on identity and selfhood, and on the weirdness of Gwen’s experience of sliding through these other selves.

This successful comic has jumped across to TV, with an extended second series of iZombie still on air right now. In the TV show, the central character Liv uses her zombie abilities to imbibe memories of those she ‘tastes’ to work surreptitiously as a detective, pretending all the time to be a mere ‘mentalist’ picking up psychic clues. It is a funny and inventive genre mash-up.

Old horror, new tricks

In the UK, two other examples of this recent change are more sombre, but are really worth tracking down. MR Carey’s acclaimed novel, The Girl With All the Gifts (2014), is a post-apocalyptic story about a group of children held in a high-security research centre, where the medics conduct interminable experiments on them while the soldiers that protect the facility threaten and abuse them (echoes of Romero’s film, Day of the Dead, surely, which shares this premise).

The medics and soldiers are among the last survivors of a kind of fungal invasion that turns humans into ‘hungries’, who lose all mental capacity and are left intent only on devouring human flesh in mindless rampages. The children are strange anomalies: they were born infected after the outbreak, yet appear to retain their humanity and intelligence.

AF Archive/Alamy

AF Archive/AlamyFor Melanie, the gifted girl of the title, this is a story of coming fully into her potential as a new, post-human, hybrid being. The novel uses lots of familiar post-apocalyptic elements, but tries to move beyond the model of permanent war that drives the battle of humans versus zombies in The Walking Dead. A film version of Carey’s book, starring Glenn Close and Gemma Arterton, comes out in 2016.

One other programme that could suggest a future for zombies is In The Flesh, which ran for just two seasons (2013-14) but was also very well received. This is another moody and reflective exploration of the undead from the perspective of the reviled and persecuted zombie. The series is set some time after the initial outbreaks and panics, and England has now reached a situation where sufferers of ‘Partially Deceased Syndrome’ can be treated with drugs, given lessons in livening-up their cadaverous faces, and contact lenses to hide their scary dead eyes.

We follow one PDS-sufferer, Kieran, who is released back to the care of his nervous parents in a small northern community that writhes with suppressed grief and rage about the losses that came with the disaster. There are friends who are now either members of a human vigilante group, and others, the Partially Dead, who have joined a resistance movement against the medical and political pacification of their true being

In the Flesh used the zombie metaphor to explore multicultural tensions in society, speaking to an era when concerns about refugee displacement, illegal immigration and ‘subversive others’ within communities were – and remain – constant concerns in the media. It was also very open to being read as an account of the threats and persecution of those ‘coming out’ sexually in closed communities.

The series showed how the zombie, that most brutal of Gothic monsters and for so long a silent, shuffling horror, can be reworked for 21st Century anxieties. Since the zombies started waking up and telling their side of the story, an exhausted trope has found a whole new lease of life.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.