How Vogue fought World War Two

Lee Miller Archives, England 2015

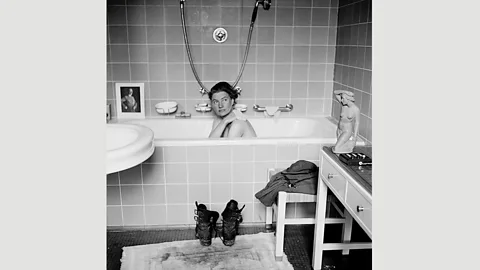

Lee Miller Archives, England 2015A new book celebrates the war photography of Lee Miller. Hilary Roberts reveals how her pieces for Vogue were part of Britain’s propaganda effort.

Lee Miller is remembered today as a woman equally at ease on both sides of the camera. She rose to fame as one of Vogue magazine’s most beautiful fashion models in 1927 and subsequently evolved into one of its leading photographers. Although she was not a formal member of the pre-war Surrealist movement, the importance of her contributions to it, both as a muse and as a photographer, are widely acknowledged. However, Miller’s most important legacy is undoubtedly her photography of World War Two. Commencing as a voluntary studio assistant for British Vogue in late 1939, Miller progressed to become one of four American female photojournalists accredited as official war correspondents to the US armed forces. In this capacity, she documented the liberation of France, Belgium and Luxembourg before accompanying the American advance into Germany. Her subjects, which included the reality of war on the front line and the horror of German concentration camps, demanded that she work without any concession to her gender in a harsh and dangerous environment from which women were traditionally excluded.

In contrast to her more experienced colleagues (such as the celebrated Robert Capa or Margaret Bourke-White), Miller was entirely unprepared for such a role. In many respects, her life before World War Two had been defined by her femininity. It attracted attention and opened doors, most notably to Condé Nast’s stable of pioneering fashion photographers at Vogue in New York. But her femininity also rendered Miller vulnerable to exploitation. The intrusive and persistent photography of her father, a traumatic childhood rape and an advertising agency’s decision to brand her the ‘Kotex Girl’ without her knowledge or consent are particularly important examples. Even Miller’s most significant lovers of this period, Man Ray, Aziz Eloui Bey and Roland Penrose, combined generous adoration with a degree of manipulation. Man Ray’s photography celebrated Miller’s beauty, but also turned her into a sexual object. The luxurious Egyptian lifestyle provided by Eloui Bey (her first husband) combined material comfort with stifling emotional isolation. Penrose offered Miller the personal and creative freedom which her other lovers had denied her, but also exploited her image in his art with an occasionally unwitting disregard for her state of mind.

The Penrose Collection

The Penrose CollectionMiller’s decision to remain in London with Roland Penrose when war broke out in September 1939 (rather than return to the safety of her native United States) changed the course of her life and transformed her photography. In the years that followed, the demands of war temporarily stripped away the constraints under which Miller had lived and worked, offering her an opportunity to employ the full range of her talents as a photographer for the first and only time in her life.

Primping propaganda

The British Ministry of Information (MoI) also influenced the diversity of Miller’s photography. The MoI was established in the University of London’s Senate House within hours of the outbreak of war in September 1939. It was responsible for the management and dissemination of government propaganda, public information and censorship. The MoI performed poorly during the first 18 months of war, hampered by inexperience, political infighting and adverse wartime events. But its effectiveness improved dramatically following the appointment of Brendan Bracken as Minister of Information in July 1941. Bracken, a successful publisher of newspapers and magazines (and a close friend of the then Prime Minister, Winston Churchill), overhauled the MoI, transforming it into an institution capable of outperforming its German rival, the Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda. In a significant new development, the MoI identified women’s magazines as a key outlet for its activities. Vogue, with its influential readership in Britain and the United States, was seen as one of the most important. Audrey Withers summarised British Vogue’s relationship with the MoI as follows:

"Women’s magazines had a special place in government thinking during the war because, with men in the forces, women carried the whole responsibility of family life; and the way to catch women’s attention was through the pages of magazines which, in total, were read by almost every woman in the country. So a group of editors were frequently invited to briefings by ministries that wanted to get across information and advice on health, food, clothing and so on. And they sought advice from us too – telling us what they wanted to achieve and asking how best to achieve it. We were even appealed to on fashion grounds. The current vogue was for shoulder-length hair. Girls working in factories refused to wear the ugly caps provided, with the result that their hair caught in machines and there were horrible scalping accidents. Could we persuade girls that short hair was chic? We thought we could, and featured the trim heads of the actresses Deborah Kerr and Coral Browne to prove it. But what about also designing more attractive caps?"

Lee Miller Archives

Lee Miller ArchivesMiller’s relationship with David E Scherman, a photojournalist at Life magazine, completed her own transformation into a photojournalist. With Scherman’s guidance, encouragement and discipline, Miller obtained accreditation as an official US war correspondent in December 1942 and began to write copy in support of her photographic essays. Miller’s photojournalism concentrated initially on the contribution of women attached to the US armed forces. Vivid and accessible features aspired to be equally relevant to Vogue’s American and British readers. Miller’s eye for a photographic image enabled her to paint pictures with words, using references that, regardless of circumstance, were uniquely feminine: ‘Little roly-poly balloons with cross-lacing on their stomachs like old-fashioned corsets sat around all shiny and clean, and the flooded areas were drying up, disclosing vulture-picked limbs of gliders which had crashed.’

Lee Miller Archives

Lee Miller ArchivesMiller’s coverage of the liberation of Europe, composed with the unique insight of an official war correspondent, propelled Vogue into uncharted territory, far beyond its normal remit. Audrey Withers struggled, as a current-affairs editor might not have done, to do justice to Miller’s work and support her:

Paper was strictly rationed. All users of paper were allowed a percentage of their 1938 consumption, and this percentage dropped to 18 percent … It was in this acutely rationed situation that I wrestled with Lee’s absorbing articles. It is always painful to cut good writing, but particularly in this case, for I felt that Lee’s features gave Vogue a validity in wartime it would not otherwise have had.

Battle of the sexes

The need to balance the demands of a prominent fashion magazine with hard-edged war reporting was never going to be easy for Miller and Withers. Miller veered from adrenaline-fuelled enthusiasm to despairing anger in an emotional roller coaster that would ultimately prove highly damaging. However, her coverage of the impact of war on European women is nuanced and perceptive. Fortitude is juxtaposed with vulnerability, kindness with cruelty. Miller highlights the damaging social divisions that were the legacy of occupation and the vagaries of war which spared some but severely damaged others. Above all, she draws attention to the deep and lasting legacy of women’s wartime experiences. By continuing to photograph the impact of war in Austria, Hungary and Romania in the months following VE Day, Miller emphasised that the consequences of war did not end with a surrender ceremony. This was a legacy which would endure for generations to come.

Lee Miller Archives

Lee Miller ArchivesWriting in British Vogue’s ‘Victory’ edition of June 1945, Audrey Withers paid tribute to women’s wartime contribution, but also asked:

"And where do they go from here – the Servicewomen and all the others who, without the glamour of uniform, have queued and contrived and queued, and kept factories, homes and offices going? Their value is more than proven: their toughness where endurance was needed, their taciturnity when silence was demanded, their tact, good humour and public conscience; their continuity of purpose, their submission to discipline, their power over machines … how long before a grateful nation (or, anyhow, the men of the nation) forget what women accomplished when the country needed them? It is up to all women to see to it that there is no regression – that they go right on from here."

For Miller, like many other women, it proved impossible to avoid a sense of regression. Her subsequent years were characterised by a sense of loss and a struggle to come to terms with the post-war world. British Vogue (despite Withers’ best efforts) could offer Miller little by way of fulfilment as a photojournalist. Traumatised and exhausted by her experiences in war-torn Europe, Miller descended into depression and alcoholism. As a professional photographer, she gradually disappeared from public view. Eventually, the femininity that had always shaped Miller’s life offered her a new form of salvation. As a gourmet cook, creating recipes informed by Surrealism, Lee Miller achieved a new fame and added a new chapter to her exceptional life.

This is an edited extract from Hilary Roberts’s introduction to Lee Miller: A Woman’s War, published by Thames & Hudson. The book accompanies an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum, London, which runs from 15 October 2015 to 24 April 2016.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.