Prostate cancer screening: What you need to know

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK's National Screening Committee has recommended that only a very small group of men at high risk of prostate cancer should be screened for the disease.

There is currently no screening programme for prostate cancer, the most common cancer in men.

But there has been some energetic campaigning for change by high-profile figures, including Sir Chris Hoy, who has terminal prostate cancer, and Lord David Cameron, who recently revealed he'd been treated for it.

The expert advice will now be consulted on for the next three months, before the screening committee gives its final recommendations to governments in the four nations of the UK in March.

What is screening?

Screening is when people are invited for a test to look for disease despite them having no symptoms.

Examples include women being invited for a mammogram to look for breast cancer or the at-home bowel cancer test posted to the home of everyone over the age of 50, every two years.

The idea is to catch cancer before someone starts to get ill and when it can still be treated.

What has the National Screening Committee recommended?

It looked at all the available evidence and concluded that screening was only suitable for:

- men with a genetic risk of prostate cancer (with a confirmed BRCA gene variant)

The advice says this group should be screened every two years between the ages of 45 and 61.

This means no screening is recommended for other high-risk groups of men such as:

- black men

- men with a family history of prostate cancer

Why did the committee come to that conclusion?

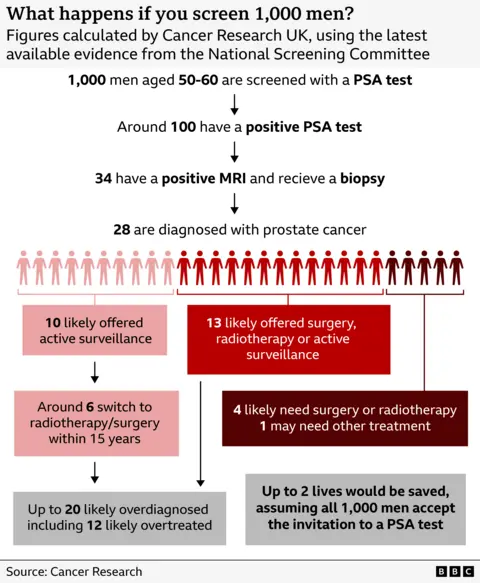

The committee said a mass screening programme for prostate cancer was likely to cause more harm than good.

Tests for the disease are unreliable, and can lead to men being treated for a slow-growing cancer that isn't going to cause them any harm. The treatment itself can cause incontinence and impotence, which can significantly affect quality of life.

Balanced against that, finding cancers early and treating them can save lives. But it's difficult for doctors to work out which cancers are going to be aggressive and spread, which means men can be treated unnecessarily.

The committee said the number of lives saved by screening does not outweigh its harmful effects on healthy men.

Why not screen all high-risk men?

Many experts had expected that all men at high risk of the disease were likely to be included in new screening plans.

But the committee stopped short of that recommendation.

Despite black men having twice the risk of prostate cancer, it said there should be no screening for black men due to "uncertainties" around its impact, and a lack of evidence from clinical trials in these men.

It also recommended no screening for men with a family history of the disease, for the same reason - too many cancers would be overdiagnosed and overtreated.

But men with specific genetic mutations called BRCA variants develop faster-growing and aggressive cancers at an earlier age, making screening for them justified.

Treating these cancers earlier is more likely to benefit those men and outweigh the potential harm from unnecessary treatment, compared to men in the general population, the experts said.

How do you test for BRCA variant?

A genetic test is needed which looks for a mutation of the BRCA 1 and 2 genes.

These gene variants can affect men and women, increasing the risk of a range of cancers, including prostate, breast and ovarian cancer.

Around three in 1,000 men have BRCA variants, but many will be unaware unless they have family members that are known carriers, and then had it confirmed with a test.

Experts say more genetic tests will need to be offered to high-risk men in future, in order to work out how many are affected.

How many men get prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men.

Some 55,000 men are diagnosed with the disease each year, and 12,000 men die from it in annually in the UK.

Will the committee's recommendations automatically be accepted?

After a three-month consultation, the committee will meet again and give its final advice to ministers in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland.

Each nation will then make its own decision on prostate screening.

Wes Streeting, Health Secretary in England, says he wants screening in place but only if it's "backed by evidence".

He said he would examine the evidence "thoroughly" ahead of his final decision in March 2026.