Dry January, teetotalism and dangers of the 'demon drink'

University of Lancashire

University of LancashireMany people welcomed the new year with a Dry January promise to swear off alcohol, a pledge also taken about 200 years ago by a cheesemonger and six other men living in industrial Lancashire.

Joseph Livesey, who became known as the 'John the Baptist of Teetotalism', founded the Preston Temperance Movement in 1832 with a pledge to "refrain from all liquor of an intoxicating quality, whether they be ale, porter, wine or ardent spirits".

That promise came on the back of a boom in both population and drinking across the newly-industrial North West.

The population of the region's cities grew massively in the early 19th Century as many swapped fields for factory work, but that increase also brought a wave of alcohol, which many saw as a tonic to tough working conditions.

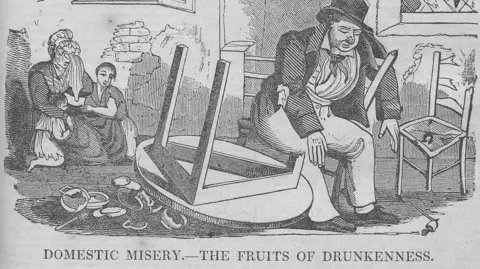

For some, that rise was coupled with a decline in morals, and so the temperance movement was born, with its proponents warning of the perils of the "demon drink".

Some academics argue the echoes of that campaigning helped pave the way for modern sobriety trends.

University of Lancashire

University of LancashireCampaigns to encourage people to stop drinking grew up in popularity across the 1800s as countries industrialised, with separate temperance movements cropping up across the US and Britain.

Preston was originally a market town whose population increased six-fold in the first 50 years of the 19th century.

Cities like Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds saw their populations increase by ten times in this period and they all went on to become strongholds of the temperance movement, said Annemarie McAllister, an honorary research fellow at the University of Lancashire.

"So you've got people who traditionally worked in the fields all rushing into these cities and they're taken away from family, taken away from tradition," she said.

"They're often living five or six families to a room and working in very difficult conditions. So what have they got to do other than drink?

"So the industrial areas were really ripe for conversion because often people who spend all the money and their time drinking are not happy. And if you can show them a way out, they'll take it."

University of Lancashire

University of Lancashire University of Lancashire

University of Lancashire"One of the jokes at the time was 'what's the quickest way out of Manchester? A penny-worth of gin,'" Annemarie said.

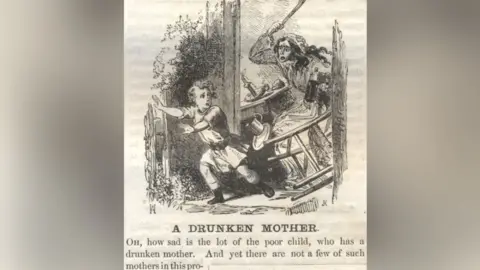

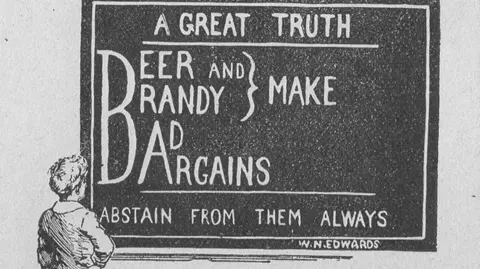

Campaigners focused on the financial benefits of giving up alcohol, which appealed to both workers and their wives, while some messages targeted children.

Little glasses of gin were sold specifically to children at the time for a halfpenny.

"There were little glasses called squibs that children could have because they were out working in the fields or later the mills and they just wanted an escape," Annemarie said.

There were more than 100 branches of the teetotalism movement targeted at men, women and children.

"Temperance was largely saying 'this is really good for your money. If you don't pass it all over the bar you can buy a house'," she said.

"And we've got a mortgage book [in the university archive] from somebody who saved up and put their money in a temperance building society and was able to buy a house."

University of Lancashire

University of LancashireAs the movement grew so did the need for entertainment. Temperance bars, coffee houses and music halls sprang up across the country so people who had taken the pledge could socialise without temptation.

The history of the movement is well-documented in the archive at the University of Lancashire, the largest in the country, which includes posters and fliers for temperance-friendly events and activities.

"There was a huge entertainment industry," Fran Robinson, archivist at the University of Lancashire, said.

"There were temperance music halls. The Old Victoria in London was the Victoria Coffee House and Music Hall at one point and we've got illustrations of the inside of it.

"They had a Temperance Music Hall in Leicester which seated thousands and attracted visiting guest speakers such as Charles Dickens."

Ashleigh Morley

Ashleigh MorleySome of those buildings are still standing but have been repurposed as shops, gyms and even pubs.

But there is one that still retains its original purpose, Mr Fitzpatrick's in Rawtenstall has been on site since 1899 and remains Britain's last original temperance bar.

It still serves tonics made from the original recipes, like dandelion and burdock, sarsaparilla and blood tonic, as well as some newly-created flavours.

"It's the only place you can do a round of shots and still drive", owner Ashleigh Morley said.

"We have people who come in for a few cordials before they go drinking and customers who don't drink but still want a bit of a treat, something a bit more exciting than a normal soft drink.

"I think they like that they can still come out and socialise without having to be around drink."

Ashleigh Morley

Ashleigh MorleyAshleigh has owned the bar for ten years, said it is "a real honour" to keep the history alive.

"There were 40 in the North West at one point, now we're the last one," she said.

"I remember coming here as a little girl, my grandma who just turned 95 this year remembers coming here."

Ashleigh said she was initially worried for the business when Covid struck but ended up seeing an increase in customers.

"When we had to close for Covid, I basically turned into a pop delivery man. I think people were boozing all the time because there was nothing else to do and they got sick of it," she said.

"Now we get quite a few 18 and 19-year-olds who don't seem to be interested in drinking the same way other generations were."

Ashleigh Morley

Ashleigh MorleyThe temperance movement began to decline after World War Two when interest in taking the pledge faded.

But Annemarie said the number of sobriety groups have been steadily increasing since the year 2000, a modern movement buoyed by social media and trends like Dry January.

"I get loads of invitations to talk to sobriety groups. There's a Manchester library group that talks about "quit lit," - women's novels and self-help books about quitting drinking," she said.

Annemarie said a lot of modern sobriety groups tend to meet online rather than in person and are largely led by women.

They all have brilliant names like "Women on the Waggon" and "Soberistas,"" she said.

"Some of them are in recovery from alcohol problems but some of them are just doing it for health reasons or even for financial reasons.

"Especially if they're young, some of them think 'why should we spend money on something that basically doesn't do anything for us and makes us feel rubbish the next day'. It's become a sort of dawning wellness movement."

Additional reporting by Kaleigh Watterson.

Read more stories from Cheshire, Lancashire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside on the BBC, watch BBC North West Tonight on BBC iPlayer and follow BBC North West on X.