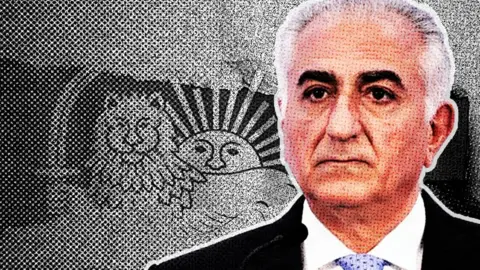

Reza Pahlavi, the exiled son of Iran's last shah at centre of protest chants

AFP

AFPMany demonstrators in Iran have been calling for the return of Reza Pahlavi, the exiled son of Iran's last shah (king).

Pahlavi himself has called for people to take to the streets. So who is the former crown prince and how much support does he have?

Groomed from birth to inherit Iran's Peacock Throne, Reza Pahlavi was undergoing fighter pilot training in the United States when the 1979 revolution swept away his father's monarchy.

He watched from afar as his father, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi - once backed by Western allies - struggled to find refuge in another country and ultimately died of cancer in Egypt.

The sudden loss of power left the young crown prince and his family stateless, reliant on a dwindling circle of royalists and well-wishers in exile.

In the decades that followed, tragedy struck the family more than once. His younger sister and brother both took their own lives, leaving him the symbolic head of a dynasty many thought was consigned to history.

Now, at 65, Reza Pahlavi is once again seeking a role in shaping his country's future.

From his home in a quiet suburb near Washington DC, supporters describe him as low-profile and approachable - a frequent visitor to local cafés, often accompanied by his wife, Yasmine, without visible security.

In 2022, when asked by a passer-by whether he saw himself as the leader of Iran's protest movement, he and Yasmine reportedly replied in unison: "Change has to come from within."

In recent years, however, his tone has grown more assertive. Following Israeli air strikes in 2025 that killed several senior Iranian generals, Pahlavi declared in a press conference in Paris that he was prepared to help lead a transitional government if the Islamic Republic collapsed.

He has since outlined a 100-day plan for an interim administration.

Pahlavi insists this new confidence stems from lessons learned in exile and from what he calls the "unfinished mission" his father left behind.

"This is not about restoring the past," he told reporters in Paris. "It's about securing a democratic future for all Iranians."

UPI/Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

UPI/Bettmann Archive/Getty ImagesBorn in October 1960 in Tehran, Pahlavi was the shah's only son after two previous marriages failed to produce a male heir. He grew up surrounded by privilege, educated by private tutors, and trained from a young age to defend the monarchy.

At 17, he was sent to Texas to train as a fighter pilot. But before he could return to serve, the revolution toppled his father's rule.

Since then, Pahlavi has lived in the United States. He studied political science, married Yasmine - a lawyer and fellow Iranian-American - and raised three daughters: Noor, Iman and Farah.

Divisive legacy

In exile, Pahlavi has remained a potent symbol for monarchists. Many remember the Pahlavi era as one of rapid modernisation and closer ties to the West. Others recall a time marked by censorship and the fearsome Savak secret police, which was used to suppress dissent and was known for human rights abuses.

Over the years, his popularity inside Iran has fluctuated. In 1980, he held a symbolic coronation ceremony in Cairo, declaring himself the shah. Although it had little practical impact, some opponents say it undermines his current message of democratic reform.

He has made multiple attempts to build opposition coalitions, including the National Council of Iran for Free Elections, launched in 2013. Most have struggled with internal disagreements and limited outreach inside Iran.

Unlike some exiled opposition groups, Pahlavi has consistently rejected violence and distanced himself from armed factions such as the Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK).

He has repeatedly called for a peaceful transition and a national referendum to decide Iran's future political system.

EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

EPA-EFE/REX/ShutterstockPahlavi has received fresh attention in recent years. Chants of "Reza Shah, may your soul be blessed" - a reference to his grandfather - resurfaced during anti-government protests in 2017.

The killing of Mahsa Amini in police custody in 2022 ignited nationwide demonstrations, propelling him back into the media spotlight.

His attempt to unite Iran's fragmented opposition drew cautious international interest, but ultimately failed to maintain momentum. Detractors argue he has yet to build a durable organisation or an independent media outlet after four decades abroad.

A controversial visit to Israel in 2023, during which he attended a Holocaust memorial event and met Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, further polarised opinion. Some Iranians viewed this as pragmatic outreach; others saw it as alienating Iran's Arab and Muslim allies.

After recent Israeli air strikes inside Iran, he faced difficult questions.

In an interview with the BBC's Laura Kuenssberg, he was asked whether he supported Israeli attacks that risked civilian lives.

He maintained that ordinary Iranians were not the target and said that "anything that weakens the regime" would be welcomed by many inside Iran - remarks that sparked fierce debate.

Backers and critics

Today, Pahlavi presents himself not as a king-in-waiting, but as a figurehead for national reconciliation.

He says he wants to help guide Iran towards free elections, the rule of law and equal rights for women - while leaving the ultimate decision about restoring the monarchy or establishing a republic to a nationwide vote.

His supporters see him as the only opposition figure with name recognition and a long-standing commitment to peaceful change.

Critics counter that he remains too dependent on foreign backing and question whether Iranians inside the country, weary after decades of political turmoil, are ready to trust any exiled leader.

While Iran's government portrays him as a threat, it is impossible to measure his true support without an open political space and credible polls.

Some Iranians still revere his family name; others fear replacing one unelected ruler with another, even under a democratic guise.

Pahlavi's father's body remains buried in Cairo, awaiting what royalists hope will be a symbolic return to Iran one day.

Whether the exiled crown prince will ever see that day - or a free Iran - remains one of the many unanswered questions about a nation still wrestling with its past.