Collapsing nuclear bunker was my secret workplace

BBC

BBCA Cold War volunteer has been recounting his "bleak and secretive" existence as a look-out in a nuclear bunker on the East Yorkshire coast.

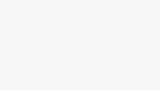

Carl Olsen, who served in the Royal Observer Corps (ROC), got in touch with the BBC after reports of the imminent collapse of the bunker on the eroding cliffs at Tunstall.

He said his job entailed "monitoring any nuclear blasts" in the event of European countries going to war.

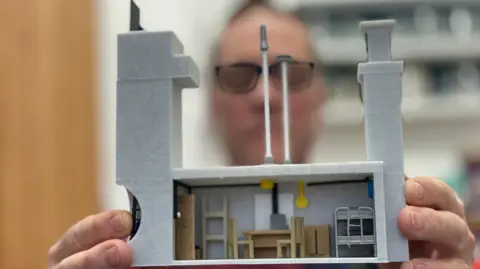

"Life in the bunker was dark, cold and damp," he recalled. " It was basic. There was just a car battery to power a lightbulb, no proper heating and a chemical toilet. But I enjoyed it and I miss it terribly."

Olsen said he was "gutted" to see images of the bunker on the edge of the cliff face, but accepted that erosion along the East Yorkshire coastline was an "unstoppable force".

The clifftop bunker is one of a number of former nuclear monitoring posts around the UK coastline, according to the historical research group Subterranea Brittanica.

Known as the Tunstall ROC Post, it is believed to have been built in 1959 and was originally more than 100 yards from the sea before erosion brought it to the brink of collapse.

Olsen said he volunteered there with a small number of colleagues from 1984 until 1991, when the facility was decommissioned by the Ministry of Defence.

"I am still sworn to secrecy on lots of things, but at the time it was very strict and it was case of 'don't tell your mum, don't tell your girlfriend' what you do," he said.

Carl Olsen

Carl OlsenThe Holderness coastline is eroding at an average annual rate of about 6.5ft (2m), according to the Environment Agency.

Maps held by the East Riding archives offer evidence of more than 30 locations disappearing from the East Yorkshire coast in the past 400 years.

Amateur historian Davey Robinson, who is filming the bunker's final days, said: "We live on one of the most eroded coastlines in Europe and this bunker hasn't got long left, perhaps just a few days."

East Riding of Yorkshire Council has urged people to avoid the area, both at the cliff top and on the beach.

Olsen's time as a volunteer followed a rise in Cold War tensions between the UK, as a member of Nato, and the Soviet Union in the early 1980s.

He said his job involved the use of "a variety of technology", including a large "pinhole" camera, a "blast gauge" and a radiation monitor.

In the event of a nuclear explosion, he would have been tasked with sending data to his commanding officers in the ROC.

Olsen said he was "grateful" there were no nuclear explosions at the time.

"If there had been, you would have been locked in the bunker with enough food and water for 28 days, or until such a time when radiation levels were safe."

One of the biggest challenges of the job was not telling his family and friends too much about it.

"People used to try to bribe me with drinks on a Tuesday or a Wednesday night down the pub to get me to tell them about my work," Olsen added.

"But I didn't. I went home drunk, but happy

"Above all, I just wanted to serve my country."

Listen to highlights fromHull and East Yorkshire on BBC Sounds, watch the latest episode of Look Northor tell us about a story you think we should be coveringhere.

Download the BBC News app from the App Store for iPhone and iPad or Google Play for Android devices