How Londoners used data to survive the Great Plague

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen plague swept through London in 1665, killing tens of thousands, people did not simply pray or flee. They checked the numbers.

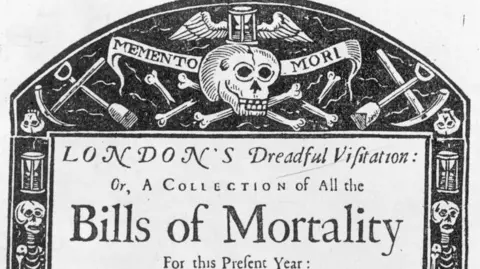

New research by Karen McBride, an accounting professor at the University of Portsmouth, argues that the weekly Bills of Mortality acted as an early public health information system, shaping how some Londoners navigated life, work and survival during the Great Plague.

Drawing on the diary of Samuel Pepys, the study suggests the published death figures were used as "quite practical decision guiding accounts or data of what was going on".

The Bills were issued weekly, listing deaths by parish across the capital. They were posted publicly and sold on street corners, allowing readers to compare week-on-week rises and falls.

Getty Images

Getty Images"They recorded the summaries of death by parish within London. So people could see where figures were rising if they compared week on week, they could see where figures were rising, where figures were falling, what was happening," McBride said.

Pepys, a naval administrator and writer living within the city walls, bought the Bills and frequently copied the totals directly into his diary.

"What was interesting to me was the fact that Samuel Pepys kept a very extensive diary. And that very extensive diary noted how he was using this data to go about his daily life at this time," McBride said.

As the numbers rose, he changed his behaviour. He planned routes through the city to avoid heavily affected parishes, reconsidered visiting friends, and relocated his wife out of London. When the totals peaked, he wrote his will.

"They enabled Londoners to use the increases and decreases to judge personal risk, where to travel, when to travel, when to leave the city, and to assess when it will be safe for them to return as well," McBride said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe figures were discussed in coffee houses and compared socially.

The Bills, McBride argues, "almost supported that idea of self-surveillance and self-governance aligning individual behaviour with the broader public health objectives without actually telling people what to do necessarily".

Accuracy was sometimes questioned. Parish officers were responsible for collecting and compiling the data, and as deaths surged, recording capacity was stretched and figures went underreported.

But doubt did not mean rejection, McBride said.

"They were nonetheless trusted enough for them to use them to guide their behaviour."

Even when people suspected understatement, rising totals heightened fear and caution. Falling numbers encouraged the reopening of shops and the resumption of social life.

The study challenges the idea that 17th Century society was simply helpless in the face of disease.

"I think they had an understanding or what they thought was an understanding of what was going on. That was wrong, but they thought they had an understanding," McBride said.

Although many believed plague was caused by "miasma" or bad air, practical measures such as isolation and distancing were adopted.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Although the ideas behind why they did these things might have been very different to what the reality was, actually it was quite helpful."

The research also highlights stark inequality. While the Bills were publicly available, literacy was limited and the ability to act on the information was "highly unequal", McBride said.

Pepys, as an upwardly mobile and wealthy Londoner, could interpret the trends, reduce contact and move his household. Poorer residents, including servants and casual labourers, often had no such flexibility.

McBride found that "for them, continued exposure was unavoidable".

There was inequality within the data itself.

"Plague deaths amongst the poor were much more likely to be misclassified, underreported, or even concealed," McBride said, whether because of parish capacity, misdiagnosis or attempts to avoid the economic consequences of shutting up a house.

Although the study does not centre on modern pandemics, McBride delved into the issue as the UK was going through its own pandemic response.

"We were all looking at numbers every day. The television was on, the numbers were there, he had numbers, he was acting on those numbers, we had numbers, we were acting on those numbers," she said.

The academic stresses that the research does not claim direct equivalence with modern outbreaks, but points to structural parallels in how societies respond to published statistics.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Whilst people truly believe that they're giving information and they're letting people know the situation and they're informing people and they're enabling people to act, that doesn't always get received equally," she said.

If information is issued without the means to respond, she suggested, it can deepen inequality rather than reduce risk.

"Whilst I completely agree with providing information, we just need to think a little bit about how that information is received."

The Great Plague of London killed an estimated 100,000 in 18 months - about a fifth of the capital's population at the time.

Between 1665 and 1666, as plague deaths climbed in the capital, some sections of society were not simply passive victims, McBride's study found.

They were reading, interpreting and reacting to the data available to them, using weekly death figures to navigate one of the deadliest years in the city's history.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk