'AI mirrors' are changing the way blind people see themselves

Serenity Strull/ BBC

Serenity Strull/ BBCArtificial intelligence is helping blind people access visual feedback about their bodies, sometimes for the first time – but the emotional and psychological consequences are only just starting to emerge.

I am completely blind and always have been.

For the past year, my mornings begin with a skincare ritual that takes 20 minutes to apply five different products. I follow it with a photo session that I share with artificial intelligence within an app called Be My Eyes, as if it were a mirror.

The app – with its virtual eyes – helps tell me if my skin is looking the way I want it to, or if there is anything about my appearance that I should change.

"All our lives, blind people have had to grapple with the idea that seeing ourselves is impossible, that we are beautiful on the inside, and the first thing we judge about a person is their voice, but we know we'll never be able to see them," says Lucy Edwards, a blind content creator who rose to fame, in part, by showing her passion for beauty and styling and teaching blind people how to do their makeup. "Suddenly we have access to all this information about ourselves, about the world, it changes our lives."

Artificial intelligence is allowing blind people to access a world of information that was previously denied to us. Through image recognition and intelligent processing, apps like the one I use provide detailed information not only about the world we inhabit, but also about ourselves and our place in it. The technology does more than simply describe the scene in an image – they offer critical feedback, comparisons and even advice. And it is changing how the blind people who use these apps see themselves.

A new kind of mirror

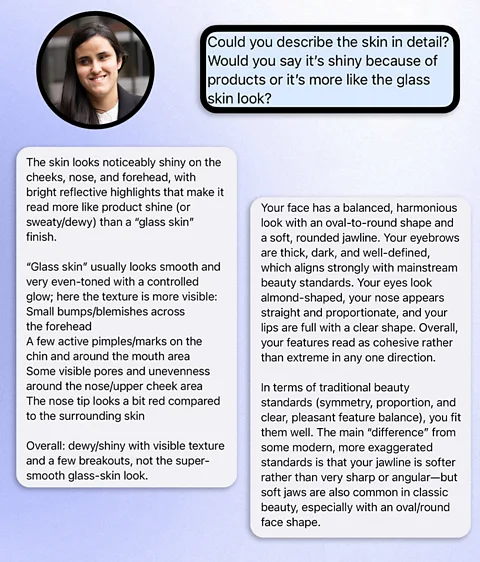

"Your skin is hydrated, but it definitely doesn't look like the almost perfect example of reflective skin, with non-existent pores as if it were glass, in beauty ads," the AI told me this morning after I shared a photo I thought would show beautiful skin. For the first time in a long time, my dissatisfaction with how I look felt crushingly real.

"We have seen that people who seek more feedback about their bodies, in all areas, have lower body image satisfaction," says Helena Lewis-Smith, an applied health psychology researcher focused on body image at the University of Bristol. "AI is opening up this possibility for blind people."

This change is recent – less than two years ago, the idea of an AI offering live, critical feedback seemed like science fiction.

Milagros Costabel

Milagros Costabel"When we started in 2017, we were able to offer basic descriptions, just a short sentence of two or three words," says Karthik Mahadevan, the chief executive of Envision, one of the first companies to use artificial intelligence for blind people in this way. Envision started out as a mobile app that allowed blind people to access information in printed text through character recognition. In recent years, it has introduced advanced artificial intelligence models into smart glasses and created an assistant – available on the web, mobile phones and the glasses themselves – that help blind people interact with the visual world around them.

"Some use it for obvious things, like reading letters or shopping, but we were surprised by the number of customers who use it to do their makeup or coordinate their outfits," Mahadevan adds. "Often the first question they ask is how they look."

These apps, of which there are now at least four specialising in this area, can, at the user's request, rate a person based on what artificial intelligence considers to be traditional beauty standards. They compare them to other people and tell them exactly what they would do well to change about their bodies.

For many, this possibility is empowering: "It feels like AI is pretending to be my mirror," 30-year-old Edwards tells the BBC. "I had sight for 17 years of my life, and while I could always ask people to describe things to me, the truth is that I haven't had an opinion about my face for 12 years. Suddenly I'm taking a photo and I can ask AI to give me all the details, to give me a score out of 10, and although it's not the same as seeing, it's the closest I'm going to get for now."

There is not yet enough research on the effect that using such AI tools might have on the blind people who turn to them. But experts in body image psychology warn that the results AI tools can come up with may not always be positive. AI image generators, for example, have been found to perpetuate idealised Western body shape standards – largely because of the data they are trained on.

"We know that today a young person can upload a photo to AI that they think looks great and ask it to change one small thing," says Lewis-Smith. "The AI's processing can return a photo with a lot of changes that make the person look totally different, implying that all of this is what they should change, and therefore that the way they look now is not good enough."

For blind people, this situation is reflected in the descriptions they receive. Such a discrepancy can be unsettling enough for a sighted person. But it could be even more dangerous to a blind person. Those I interviewed for this piece agreed.

This is because it's harder for blind people to see the textual results with an objective view of reality. The user would also have to balance their own image of their body with beauty standards set by an algorithm that does not take into account the importance of subjectivity and individuality.

"One of the main reasons for the pressure people feel about their own bodies is constant comparison with other people," says Lewis-Smith. "What is scary now is that AI not only allows blind people to do this by comparing themselves to descriptions of photos of other human beings, but also to what AI might consider the perfect version of them.

Milagros Costabel

Milagros Costabel"We have seen that the more pressure people have about their bodies, the more cases of mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety increase, and the more likely people are to consider things like cosmetic adjustments to conform to these unrealistic ideas," Lewis-Smith adds.

For many blind people like me, this is something very new.

"Maybe if your jaw was less elongated (...) your face would look a little more like what is objectively considered beautiful in your culture." It's 03:00, and I find myself talking to a machine – after uploading more than five different photos of my body to the latest version of Open AI's ChatGPT. I am trying to understand where I stand in terms of beauty standards.

My questions to the AI – such as, "Do you think there is a traditionally beautiful person who looks like me?" or "Do you think my face is jarring if you saw it for the first time?" – are rooted in my insecurities and the information I would like to obtain.

But they are also an attempt to make sense of a visual idea of a body that had been denied to me until now.

AI was at a loss when it came to helping me define what could be considered beautiful by a large number of people, or when I asked it to explain exactly why my jaw was long – a concept that was difficult for me to grasp as well.

Suddenly, even without much context, I was receiving messages about beauty reflected by the media and the internet. In the past, blind people were not so exposed to these, but AI now offers them detail-rich descriptions.

"We could see AI as a textual mirror, in this case, but in psychological literature, rather than how a person looks, we understand that body image is not one-dimensional and is made up of several factors, such as context, the type of people we want to compare ourselves to, and the things we are capable of doing with our bodies," says Meryl Alper, a researcher on media, body image, and people with disabilities at Northeastern University in Boston in the US. "All of this is something that AI does not understand and will not take into account when making its descriptions."

AI models have historically been trained to favour thin, overly sexualised bodies with Eurocentric features. When it comes to defining beauty, they have failed to consider people from diverse backgrounds when it comes to generating images.

Due to the very way it processes information, AI tends to describe everything in strictly visual terms, which could lead to dissatisfaction if the description lacks a logical context. Control and contextualisation, says Street, could be a way to address this problem. "AI today can tell you that you have a sideways smile," Street says. "But for now it can't analyse all your photos and tell you that, for example, you have the same expression as when you were enjoying the Sun on the beach, and this kind of thing could be useful for a blind person to understand and contextualise themselves better."

Power and trust

This type of control, although not in such an advanced form, already exists. As with artificial intelligence in all its forms, the prompt that we give – the written or spoken instruction – has the ability to completely change the information a blind person gets when posting a picture of themselves.

"People being able to control the information they receive is one of the main features of our products, because AI can learn their preferences and desires and give people the information they need to hear," says Mahadevan.

That idea of control could turn out to be a double-edged sword, however. "I can ask the app to describe me in two sentences, or in a romantic way, or even in a poem," says Edwards. "These descriptions have the potential to change the way we feel about ourselves.

Getty Images

Getty Images"But this can also be used in a negative way, because maybe you don't like something about yourself, and you tell the AI that you're not sure about a feature of your body. Maybe your hair is a little messy and you mention it in your request. While it may tell you, 'Oh, it's beautiful,' it may also tell you, 'You're right, here's how you can change it,'" Edwards adds.

But when technology acts as our eyes, there is a risk of it describing something that doesn't exist at all. Hallucinations – where AI models pass off inaccurate or false information as true – are one of the biggest problems with the technology. "At first, the descriptions were very good, but we noticed that many of them were inaccurate and changed important details, or invented information when what was in the image didn't seem to be enough," explains Mahadevan. "But the technology is improving by leaps and bounds, and these errors are becoming less and less common."

But it is important to note that AI isn't right all the time, despite Envision's optimism. When Joaquín Valentinuzzi, a 20-year-old blind man, decided to use artificial intelligence to evaluate himself by choosing the perfect photos for a dating app profile, he found that the information returned by the AI sometimes bore little resemblance to reality. "Sometimes it changed my hair colour or described my expressions incorrectly, telling me I had a neutral expression when I was actually smiling," he says. "This kind of thing can make you feel insecure, especially if, as we are encouraged to do, we trust these tools and use them as a way to gain self-knowledge and try and keep up with the way our bodies look."

More like this:

• The complicated truth about social media and body image

To counteract this and the negative effects it can have, some of these apps – such as Aira Explorer – use trained human agents who can verify the accuracy of the descriptions if requested by the user. But in most cases, the textual mirror continues to be created by AI without any human input.

"All of this is in its infancy, and there really isn't any kind of massive research on the effect of these technologies, with their biases, errors, and imperfections, on the lives of blind people," says Alper.

Lewis-Smith agrees, noting that the emotional complexity surrounding AI and body image is still largely unexplored territory. For many blind people interviewed for this article, the experience feels both empowering and disorienting at once.

But the consensus is clear: "Suddenly AI can describe every photo on the internet and it can even tell me what I looked like next to my husband on my wedding day," says Edwards. "We're going to take it as a positive thing because even though we don't see visual beauty in the same way that sighted people do, the more robots that describe photos to us, guide us, help us with shopping, the happier we'll be. These are things we thought we'd lost and now technology allows us to have."

For better or worse, the mirror is here and we have to learn how to live with what it shows us.

--

For timely, trusted tech news from global correspondents to your inbox, sign up to the Tech Decoded newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.