The disease that lurks for decades

Mundo Sano

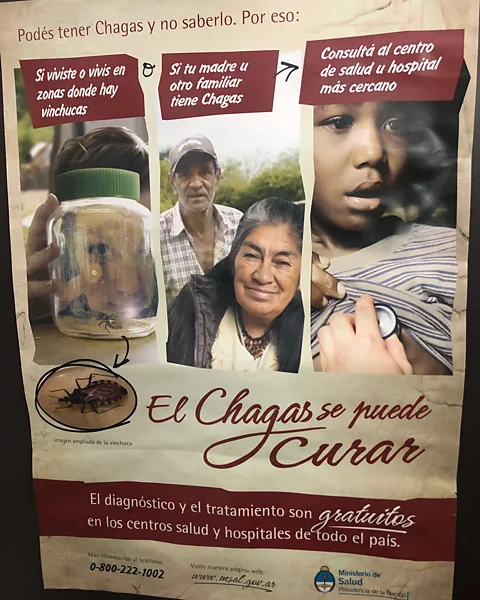

Mundo SanoChagas disease causes misery in poor communities around the world, and may lead to 10,000 deaths a year. Health workers are trying new methods to ease suffering.

Lucrecia Ramón Barrera’s home, in the northern Argentine province of Santiago del Estero, hosts a menagerie. Several skinny dogs seek shade wherever they can. Two enormous pigs and a handful of piglets share their pen with fuzzy chicks. Dotted around the space are homemade wooden birdcages, each home to a tiny bird. And chickens run freely all around the property – including into the main house, where the 43-year-old Barrera and most of her six children sleep in a stick-topped structure that Barrera built herself. The chickens have free rein partly to keep them safe from foxes (not to mention the occasional puma that prowls around this rural zone).

It’s common for homes in this dusty area to be built without doors or roofs, without electricity and running water, and for inhabitants to share their homes with animals. Unfortunately these are ideal hiding conditions for the triatomine (also known as the ‘kissing bug’ or vinchuca locally).

Triatomines have an unpleasant modus operandi. The bugs crawl out at night to bite exposed skin, often on a sleeping human’s face, feeding on its victim’s blood. The triatomine also defecates or urinates near the bite, and when the victim scratches the bite, a single-celled parasite carried in the insect’s faeces enters the body.

The parasite in question, Trypanosoma cruzi, causes Chagas disease. A bite from a kissing bug carrying the parasite, while Barrera was asleep, is likely how she became infected.

Christine Ro

Christine Ro“I felt pain in my chest,” Barrera recalls of the onset of her symptoms. “I didn’t want food.” She’s feeling better now after a two-month course of antiparasitic drugs, and is grateful for the comprehensive medical and social support, all provided free of charge to Chagas patients by the Argentine government.

Periodic spraying of insecticide helps, which is happening in Barrera’s home today. The fumigation team is accompanied by a Chagas-specific social worker who can check on whether the family has enough food and money, and whether Barrera needs transport to a medical centre.

This level of support is unusual, both in Argentina and globally. Chagas disease has been called the most neglected of all the neglected tropical diseases. It causes about 10,000 deaths a year and affects seven million people worldwide, but few of those affected will ever receive treatment.

You might also like:

- The tiny kingdom fighting an epidemic

- The neglected disease killing thousands

- The other virus that worries Asia

But the government in this pocket of Argentina, and health workers and researchers around the world, are trying to reverse the historical neglect of Chagas. They’re hoping to raise the profile of the disease while they lower its prevalence – and there are some reasons for optimism.

Christine Ro

Christine RoWhy Chagas disease is such a challenging foe

María Jesús Pinazo is an upbeat, perpetually smiling person, but it can be hard for anyone to stay positive when dealing with Chagas disease.

Chagas is fiendishly difficult to combat at every step: diagnosis, treatment and aftercare. Pinazo knows this well, as she’s spent her entire career caring for patients with Chagas disease and researching how to treat it.

First of all, diagnosis remains extremely challenging. One estimate is that fewer than 10% of people with the illness are actually diagnosed – and this may be a severe underestimate. Currently, diagnosis often requires several tests in a reference laboratory staffed by knowledgeable health workers, which simply isn’t feasible for the remote communities where many Chagas cases are found.

Many infected people quietly carry the infection without knowing, in some cases for up to 30 years if it doesn’t prove fatal earlier. The disease is a slow-moving time bomb, which can result in heart failure or gastrointestinal problems even decades after infection. Thus, it’s often referred to as la enfermedad silenciosa (‘the silent illness’).

For the few patients who do learn that they have Chagas disease, treatment options are dispiriting. There are only two drugs being used to treat the disease, which were developed through the veterinary industry in the 1970s. Side effects under treatment with the drug benznidazole, which currently lasts two months, can be intense. Many patients stop treatment early.

“We lack the ideal drug. It doesn’t exist,” says Oscar Ledesma Patiño, a pediatric specialist at the Chagas Centre in Santiago del Estero, who has been working on Chagas since the 1970s.

It’s hard for Pinazo to face patients and tell them that the only real option is to give them a drug they’ll need to take for 60 days, which may have awful adverse effects.

Even after an arduous treatment, doctors can’t even tell patients if they’ve been cured. “The immune system forgets this parasite,” Pinazo says. It can take eight to 10 years for tests to confirm that the parasite is truly gone for good.

“It is the worst panorama ever for a clinician,” says Pinazo.

Christine Ro

Christine RoUltimately, while research innovation and dogged prevention continue apace, much of the progress against Chagas comes down to political will, which can be very uneven. In some Argentinian provinces, some of the funds allocated to the disease aren’t even spent. The neglect and underuse of resources intensified during the Covid-19 pandemic as house-to-house spraying stopped in some areas but not others, and some healthcare workers were reassigned to manage the pandemic.

Santiago del Estero is unusually well-resourced when it comes to fighting Chagas, compared to neighbouring provinces. And despite the relatively high resources available in Santiago del Estero, the level of government attention to this disease still meets local resistance. One social worker reports having to visit an at-risk woman for two months before she finally agreed to let fumigators spray her house.

Beyond this particular hotspot, the disease is colonising new areas. Ezequiel José Zaidel, a cardiologist and coordinator of the Interamerican Society of Cardiology, gives the example of a 50-year-old woman hospitalised at his medical centre several weeks ago due to an extremely slow heartbeat. “She required an urgent pacemaker implantation,” Zaidel explains. The patient, who was born in rural Paraguay and moved to Buenos Aires as a teenager, recollected seeing kissing bugs in her mud home as a child. She also remembered that some of her aunts had died suddenly in Paraguay. “We then called the rest of the family and found Chagas disease in two sisters and one young niece born in Buenos Aires, who was sent to receive antiparasitic treatment.”

But it’s not always possible to trace family medical histories across borders. The disease has started to show up in Spain, the United States, and other countries with significant populations of migrants from Latin America.

Health workers in the US, for instance, are likely to be unfamiliar with Chagas. And there may be further barriers of language and migration status that complicate diagnosis and treatment.

Progress in the fight against Chagas

Thankfully some hope is on the horizon. The technology already exists for the rapid tests that could transform diagnosis. These “would resolve a serious problem for us,” says Ledesma Patiño.

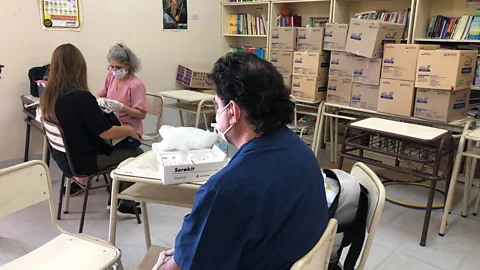

The non-profit Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi)is funding a trial of rapid tests in Santiago del Estero. But they haven’t yet been rolled out at the national level, and the Chagas officials in Santiago del Estero are waiting for the green light from the national government. Trials need to be carried out first in each location, because the accuracy varies depending on the context (for instance, based on which species exist locally).

Christine Ro

Christine RoDNDi has also been running clinical trials of shortened treatment regimens with benznidazole, though with relatively small samples thus far. While benznidazole is an imperfect tool to fight Chagas, it’s the best one currently available, so at least reducing the treatment period from two months to two weeks can make it easier to handle any side effects.

Of course, new drugs are needed as well, and Pinazo is hoping that alternatives will be found within six to eight years – although that may be optimistic. “We have to have it quickly,” she emphasises. “If not it is nonsense.”

As well, researchers have been sequencing the kissing bug’s microbiome to better understand the bacterial environment for transmission of the infection. Perhaps one day this could lead to genetic manipulation of the kissing bug, which could block the development of the parasite. This would reduce dependence on insecticides.

For now, the combination of active testing, education and spraying of insecticides is clearly having an effect. According to Ledesma Patiño, the prevalence of Chagas infection within Santiago del Estero’s sampled blood tests has declined dramatically, from 30% in 2005 to 5% now.

What’s helped has been a focus on certain groups at risk, such as pregnant women. With improved control of insects, “mother-to-child transmission became the predominant way of infection”, Zaidel comments. For him, “active screening and treatment of newborns is a must, and can’t be interrupted due to political issues, pandemics, or anything”.

Recognising this, the health foundation Mundo Sano has a campaign called “Not a single baby with Chagas”, which works toward eliminating of transmission during pregnancy. And in the province of Santiago del Estero, every pregnant woman is tested for Chagas. If they’re found to have Chagas, their babies are also tested soon after birth.

Christine Ro

Christine RoBut for all the technical and scientific progress against Chagas, the disease will persist as long as there is poverty and challenging living conditions. Mundo Sano is recognising this with its programme of upgrading houses in at-risk areas of Santiago del Estero. This comes at the request of residents, and is part of a package of support which includes insecticide spraying and advice on house improvements to limit kissing bug refuges.

This kind of approach could help avert reinfection in Barrera’s home.

Until then, life will continue as normal for the family – listening to a battery-powered radio tied to a clothesline, drinking endless cups of mate, and sharing their living quarters with their many animals – while parasitic insects continue to burrow their way in.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter orInstagram.