Should astronauts abandon the space station?

Nasa/Getty Images

Nasa/Getty ImagesThis month, the International Space Station marks 20 years of constant human habitation. But should astronauts now hang up their spacesuits and leave space exploration to robots?

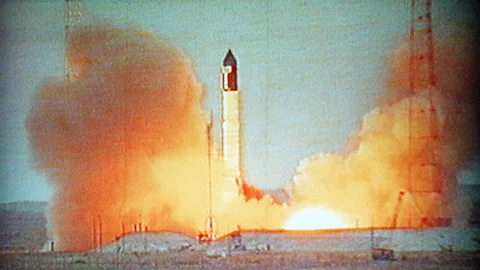

At 6.50am GMT on the morning of 20 November 1998, I was crouching behind a rock in the bitter cold of the Kazakh Steppe clutching a mobile phone to my ear. The snow-dusted ground blended into the grey of the sky. Behind me, a makeshift PA squawked garbled Russian, but most of the Russians it was meant for were inside a nearby wooden shelter enjoying a celebratory vodka.

In the far distance, and barely discernible against the monochrome landscape, a white Proton rocket stood silent, isolated on the launchpad. Then suddenly with a flash and crackling roar, it began to rise from the ground.

As the rocket accelerated into the sky and disappeared into the clouds, I described the scene live to BBC radio listeners. It was, after all, a historic occasion – the launch of the Zarya module, the first stage of the International Space Station (ISS). But despite my best descriptive efforts, the event didn’t lead the news.

The fact that the BBC sent a junior radio reporter to cover the launch, rather than a senior correspondent, proved how editors – and the public – viewed the story. Already the ISS was years late and massively over-budget. The head of science at the UK’s space agency called the station “an orbiting white elephant” and the UK declined to fund it. Many doubted the ISS would ever be completed.

You might also like:

They were wrong. The size of an American football pitch and with living space equivalent to a six-bedroom house, the ISS is, by any measure, a remarkable feat of engineering. Completed at a cost of some $150bn (£116bn) – paid for by the taxpayers of the United States, Russia, Europe, Canada and Japan – it’s been home to astronauts for 20 years.

Since Expedition-1 to the station in November 2000, humans have had a constant presence there, living and working in orbit. At the last count, 243 astronauts from 19 countries have visited the ISS and it has hosted some 3,000 scientific experiments.

Yuri Kochetkov/AFP/Getty Images

Yuri Kochetkov/AFP/Getty ImagesNevertheless, doubts over whether the station is value for money – and value for the rest of us back on Earth – remain. With the world in the grip of a pandemic and the existential threat of climate change looming over the planet, some are again questioning the motives for sending humans into space.

“I would certainly rate the ISS as not worth a 12-figure sum,” says the UK’s Astronomer Royal, astrophysicist Lord Rees of Ludlow. “None of the hundreds of people circling around in the International Space Station have done any worthwhile science sufficient to justify even a tiny fraction of the money the Shuttle and space station have cost us.”

Lord Rees argues instead of the ISS, we should be spending public money on the robotic space science missions that have transformed our view of the Universe. Right now, spacecraft are sending back pictures and scientific data from Mars, Jupiter and the twin Voyager probes have left our Solar System, becoming the first human-made objects to enter interstellar space. In 2014, we even managed to land a probe on a 4km-wide (2.5 miles) comet travelling at 55,000km/h (34,375mph), 56 billion kilometres (35 billion miles) from Earth.

“If we ask how newsworthy [the ISS] has proved, there’s been far more news from Hubble and missions to Mars, Jupiter and Saturn than there has from the space station,” Rees says. “The space station makes the news when Chris Hadfield sings or when the toilet doesn't work, I think it's increasingly hard to justify spending public money on sending humans into space in future.”

A lot has changed since I witnessed that first launch in 1998. Whereas the ISS has been almost entirely publicly funded, the future of human space exploration is being driven as much by space agencies as the ambition of private individuals like SpaceX’s Elon Musk and the world’s richest man, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

While Nasa aims to return humans to the Moon by 2024, Musk plans to establish a settlement on Mars and even talks about dying there (but not on impact). Bezos prefers the idea of giant rotating colonies in space. But that dream of leaving the worries of Earth behind is not shared by everyone in the space community.

Nasa/Getty Images

Nasa/Getty Images“The enterprise of human spaceflight is corrupt,” says Linda Billings, a researcher at the National Institute of Aerospace and analyst specialising in space. Once a former advocate for human spaceflight, serving on the US National Commission on Space, she’s changed her mind. One of her recent publications is titled: ‘Should Humans Colonise Other Planets? No.’

“By corrupt, I mean broken,” she explains. “It's inefficient. It's overly expensive. And the bottom line for me is, what's the point?”

She argues that the motivation for flying humans into space is not driven by science. “The reasons rest upon a rationale which I find very shaky – an ideological rationale that really is propelled by a belief in the value of conquest and exploitation,” she says.

You could argue that without conquest and exploitation there would be no civilisation. And few would doubt the courage of pioneering astronauts strapping into experimental rockets and venturing into orbit and onto the Moon. Billings, however, questions our motivation and says we can still explore and use space – for science and the satellite technology we take for granted – but people should remain on Earth.

“Nasa's doing tremendously good work studying climate change and what happens is our political system and the corporate world says, thank you very much but we don't care,” she says. “How does human space exploration benefit all the people in Bangladesh and India who depend on water for their livelihood and are eventually going to be washed away by it? I worry about this every day.”

And this touches on an inequality at the heart of the human space programme – who gets to go? With one exception, cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, the first generation of astronauts were all white men. Most were military test pilots. Today, most astronauts are still pilots and many are ex-military.

In July 1969, shortly before Apollo 11 launched to the Moon, black civil rights protestors from across the southern United States gathered at Cape Canaveral to highlight the inequalities of sending men into space when many in the country were living in poverty. A US Civil Rights attorney (and space enthusiast) Robert Patillo predicts similar arguments in the future.

“We'll have privately owned space stations by the 2050s where people will be able to go on vacation and, if you have the income to do it, we'll probably have Moon-based ones by the end of the century,” Patillo says.

Paul Hennessy/NurPhoto/Getty Images

Paul Hennessy/NurPhoto/Getty Images“The question is going to be: how do we ensure that the people who are benefiting are paying their fair share back here on Earth so that we can have things like health care, clean water and an education system?” he says. “Just the fundamentals of what has to be done to keep the society functioning underneath them.”

Even if Musk eventually makes it to Mars, it’s unlikely that Martian society will be anywhere close to the utopia some people dream of. The planet’s surface is a dusty red desert… there’s no air to breathe, food to eat and the water is locked away in ice.

The first settlers will be an average 225 million kilometres (140 million miles) away from home and any call for help will take up to 24 minutes to reach the Earth, and another 24 to get a reply. (You can read more about the challenges of colonising space here.)

“Humanity is not ready to leave the Earth,” says Billings. “We have a lot of intellectual, social, moral evolution that we need to do before we can even think about it.”

So, are we getting ahead of ourselves in the rush to colonise space? Lord Rees believes we have to accept our limitations as a species that’s evolved for life on Earth.

“We shouldn’t see ourselves as the culmination of evolution,” he says. “It will only be a few centuries, at most, before entities could exist, which are very different from human beings – they could be flesh and blood, genetically modified, or they could be electronic – that could certainly include species or entities exploring far beyond Earth, which are in some sense our descendants.”

After 20 years of being a home from home, the ISS has taught us that living and working in the vacuum of space – sealed in a tin can, eating processed food and drinking recycled sweat and urine – is challenging and expensive.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of the space station has been to give us a better appreciation of the Earth. Talk to any astronaut about their experience and it’s the incredible view of the world from the window that inspires them – and us – the most.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter orInstagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.