The ultimate in Italian cool

Alamy

AlamyMarcello Mastroianni was far more than his ‘Latin Lover’ image – he deserves to be remembered for his extraordinary range, writes Caryn James.

As the aging Casanova in La Nuit de Varennes (1982), Marcello Mastroianni politely turns down a young woman’s offer to be his 1000th sexual conquest. His powdered face as white as his wig, his eyes sagging and world-weary, he says: “This old man didn’t take your breath away. It was his name, his reputation, his past. Today those things are gone.”

Mastroianni’s own attractiveness persisted to the end of his life. He died in 1996 at 72. But his role in Varennes is a sly comment on and subversion of his on-screen image as the ultimate womaniser in classic films like Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960) and Vittorio De Sica’s Marriage Italian Style (1964). One of his many late-career triumphs, La Nuit de Varennes suggests how wisely he aged, how subtly he acted, how much more there was to him than the simplified image.

Alamy

AlamyRescuing him from that stereotype is one of the aims of a large Mastroianni retrospective in New York, a collaboration between the Film Society of Lincoln Center and Istituto Luce Cinecittà, which provided many film prints.

The series is called Il Bello Marcello, or Handsome Marcello. “It should be called Marcello: Behind the Latin Lover,” says Florence Almozini, Associate Director of Programming for the Film Society and one of the series’ primary curators. “His range is incredible. Maybe the idea of him is, ‘He was just one of those good-looking Italian guys.’ But he’s a very serious actor and played a lot of different roles in comedy and drama. I don’t think people realise what an intense actor he was.”

The series’ 28 films feature an astonishing range of master directors, including Luchino Visconti and Michelangelo Antonioni. That Mastroianni was sought out by so many of the 20th Century’s greatest filmmakers is a testament to his own versatility, talent and accomplishment.

Alamy

AlamyHis breakout came in the late 1950s in two films that reveal his career-long pattern of embracing both popular and high art. In the crowd-pleasing Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958) he is part of a gang of bumbling robbers trying to pull off a heist. In Visconti’s sumptuous, atmospheric White Nights (1957), he deludes himself that a woman he has just met will jilt her former lover for him. As Mastroianni wanders the night streets, shot in lush black and white, his character’s emotions shift so gradually and convincingly that when his declaration of passion arrives it seems both inevitable and surprising.

He was already in his early 30s by then. “Probably because he started making his bigger films a little later in life, he was very mature in his acting, especially in White Nights,” Almozini says. “He plays a young romantic guy, but a 20-year-old would not be able to carry that over” with the same depth.

Alpha male?

He took on more roles in art films, many of them overlooked then or hard to find today. He played the mad 20th Century aristocrat who believes he’s a medieval emperor in Henry IV (1984), Marco Bellocchio’s adaptation of the Pirandello play.

And among the retrospective’s rarely-screened gems is Visconti’s The Stranger, based on Camus’ novel, with Mastroianni as the existential hero detached from life and his own murder conviction. In a film with dialogue as terse as Camus’ own writing, the film and the depiction of its enigmatic character rests on the flickering changes to be read on Mastroianni’s face.

Alamy

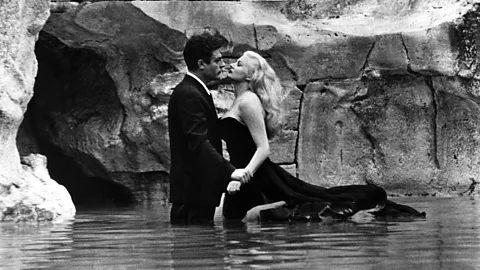

AlamyWhen The Stranger arrived, in 1967, Mastroianni was stretching beyond the image that had already taken hold with his most iconic role. In La Dolce Vita, he is a hedonistic journalist named Marcello Rubini, who chronicles and takes part in the good life. The film’s portrait of celebrity culture speaks beautifully to our own age. The film even gave the world the term ‘paparazzi’, from a minor character, a pesky photographer called Paparazzo. Tourists in Rome still try to leap into the Trevi Fountain as Anita Ekberg did, calling out “Marcello!”

Mastroianni was a also a cad in enduring, early ‘60s romantic comedies. But those roles were more complex and ambiguous than the received opinion makes them seem. His macho characters are often outwitted by the women he is trying to use.

Often that woman was played by Sophia Loren, his most frequent co-star. In Marriage Italian Style, Mastroianni is a wealthy man who refuses to marry Filumena, his long-time mistress, played by Loren. After a death-bed hoax and other farcical, sometimes heart-rending twists, Filumena gets her way.

Alamy

AlamyIn Divorce Italian Style (without Loren), Mastroianni’s character is willing to murder his wife to be free of her and marry his young cousin. The character is also a cuckold, with slicked-down patent-leather hair and a silly little moustache. Mastroianni deftly makes the man sincere yet ridiculous.

In one sense those films are time capsules of an era when men were in charge of women, who were mothers or whores, and when sex scenes on screen were discreet. The lovers stay clothed, or the camera cuts away, making the sex almost quaint next to today’s movies. The heat is under the surface.

At the same time, Mastroianni and his co-stars capture the back-and-forth of power struggles and manipulation, the pain of one partner loving more than the other, the eternal dynamic of romantic relationships. Those emotions still emanate strongly from the films, despite the trappings of the culture and period.

Ageing gracefully

Almozini says about those films: “Because they are Italian from 50 years ago, sometimes they’re a little hard to take as a woman, but I think people can see behind certain sexist and misogynistic aspects.” Mastroianni’s enlightened performance helps, she says. “There’s a lightness to him, like he’s winking at you, ‘Don’t take this too seriously.’”

Mastroianni often worked against his Latin lover image. He gained one of his three Oscar nominations for the 1977 drama A Special Day (like Varennes, directed by Ettore Scola). He plays a homosexual in Mussolini’s Italy who establishes a deep emotional connection with Loren’s character, a harried mother.

Alamy

AlamyAs he aged he also leaned into the image with wry wit, as he did in Varennes, in which Casanova joins a carriage of aristocrats escaping Versailles at the start of the French Revolution. And he continued to work with the great directors of world cinema. In 1986, he made films with two of them.

In Theo Angelopoulos’ eloquent, deeply moving The Beekeeper, Mastroianni plays Spyros, a retired teacher on a road trip, who encounters a manipulative young woman. With little dialogue and slightly stooped shoulders, he reveals Spyros’ deep discontent. When he finally has sex with the woman, it is the desperate move of a man near the end of his life, not a May-December romance.

That same year Mastroianni made Ginger and Fred, his last film with Fellini. Their collaboration is one of cinema’s richest. The actor became the director’s alter ego in films like 8 1/2 (1963) and City of Women (1980), seamlessly assuming that mantle.

In Ginger and Fred, he and Giulietta Masina play a dance team reunited after thirty years for a nostalgic appearance on a television variety show, a typically comic Fellini circus. Poignant but never sad, Mastroianni’s character is balding but his hat is still at a rakish angle, his eye still roving.

Like so many great actors, Mastroianni’s ease on screen made his work seem as if he were inhabiting roles that came naturally, without a second thought. To the contrary. He was as shrewd and talented as he was bello.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.