Do musicians get better with age?

Getty Images

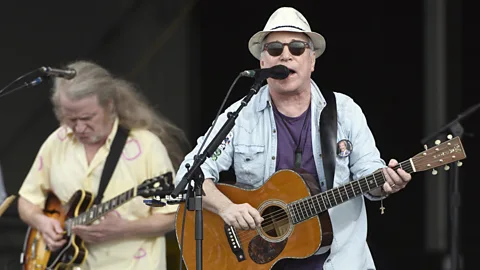

Getty ImagesAt 74, Paul Simon is arguably producing the best work of his career – and he’s not alone. Many musicians find it’s better not to shut up and play the hits, writes Jim Farber.

Nick Lowe looks at many older pop stars with a mixture of embarrassment and dread. He calls these creatures “thinning-haired, jowly geezers who still do the same schtick they did when they were young, slim and beautiful. That’s revolting and rather tragic.”

Small wonder, starting in his 50s, Lowe went a dramatically different way. The now 67-year-old pioneer of ironic 1970s punk-pop morphed in middle age into a sincere balladeer, emphasising the grizzle in his viewpoint and the wear in his voice. In case anyone missed his intention, Lowe titled one album in that vein At My Age.

Lowe isn’t alone in refusing to squeeze himself into the jeans of his younger self. Over the last decade, an increasing number of seasoned stars have not only shown their talents to be well-preserved, they’ve experienced growth spurts worthy of an adolescent.

There’s an important distinction to be made here: plenty of late-stage stars continue to release new music, and to command top dollar on tour, without remotely improving or significantly varying their classic style. Include in that long list the Rolling Stones, Billy Joel, Paul McCartney, Fleetwood Mac, AC/DC, and so forth.

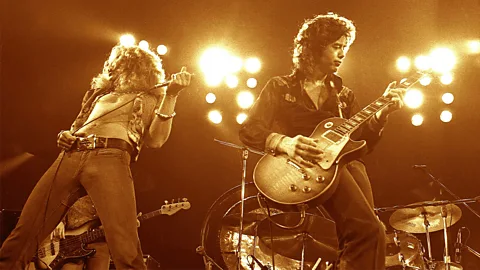

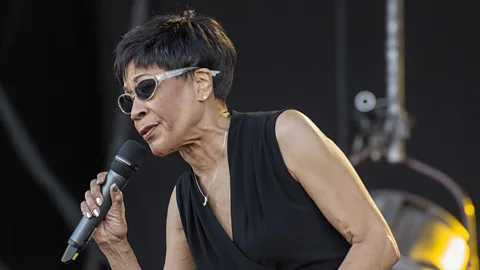

At the same time, an ‘elder awakening’ has taken place, a trend whose pioneer may well be Johnny Cash. During the last decade of his life – which came to an end at the age of 71 in 2003 – Cash found a bracingly raw, and newly urgent, sound, midwifed by producer Rick Rubin on the American Recordings series. A few years later, 67-year-old Robert Plant pushed just as boldly beyond his vaunted legacy with Led Zeppelin. Instead of agreeing to a lucrative Zep regurgitation tour with Jimmy Page in 2007, Plant forged a freshly rural sound with Alison Krauss that resulted in the number one, platinum-selling work Raising Sand, which took the album of the year Grammy in 2008. Likewise, 76-year-old Mavis Staples has lately enjoyed one of the most productive periods of her half-century career, chronicled on her recent albums produced by Jeff Tweedy of Wilco.

Ageing soulfully

It seems age has flattered soul stars to an unusual degree. Another such artist, Bettye LaVette didn’t find her audience until the age of 60. Over the last decade, the now 70-year-old star has issued four albums which have earned her the critical acclaim and fan devotion that she never experienced in the first four decades of her career. In that same vein, the Otis Redding-like singer Charles Bradley didn’t get to release a full album until he was 62, No Time For Dreaming, on the prestigious Dap-Tone label. His subsequent work has proven relevant enough to be sampled by hip-hop stars like Jay-Z and Asher Roth. In April, the 67-year-old Bradley issued a brand new work for the imprint, aptly titled Changes.

Alamy

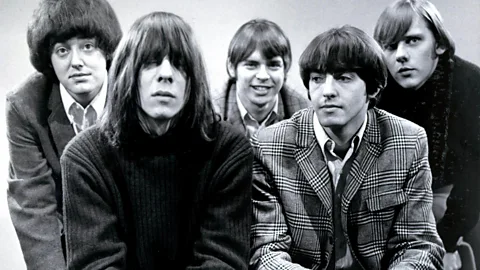

AlamyA somewhat stranger re-emergence came in March of this year. One of pop’s great, lost stars of the ‘70s – 66-year-old Emitt Rhodes – finally woke up, Rip Van Winkle-style, to release his first new music in 43 years. The album, titled Rainbow Ends, found Rhodes in a voice very much changed from the Paul McCartney-esque chirp of his youth. Now, he has the movingly weary huff of a Warren Zevon. The album saw Rhodes topping his youthful flair for impeccable melodies, offering some of the most finely-turned pop songs of the last 20 years.

Over the last month, this awakening has sharply spiked with three key releases: Bob Dylan just issued his second album of standards (titled Fallen Angels), finding yet another voice and character for this 75-year-old changeling. His performance offers a witty and wistful take on American romantic classics made famous by the likes of Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland. At the same time, 76-year-old William Bell, a cult soul star of the ‘70s who co-wrote the blues standard Born Under A Bad Sign, just put out his first major label album in 40 years, This Is Where I Live. The stirring music makes the most of Bell’s steep well of experience, creating songs of crushing rumination and wise reflection.

Parsley, sage, rosemary and time

That’s all impressive stuff. Yet none of these re-born seniors can claim a more radical, or assured leap ahead than Paul Simon has with his new solo album, Stranger to Stranger. On it, the 74-year-old star explores places he has never been before. That’s saying something for an artist who made sonic globe-trotting his thing, ever since late ‘60s creations like the Peruvian salute, El Condor Pasa. Now he is finding rhythms and tonalities that aren’t fixed in any single place.

Stranger to Stranger does travel to some recognisable locales, including South Africa (à la Graceland), Peru and New Orleans. Yet, some of the album’s most adventurous effects involve instruments dreamt up by 20th-Century US musical theorist Harry Partch in a musty university. Simon employed Partch contraptions like the Chromelodeon and Cloud-Chamber Bowls, which use micro-tonal scales to splay octaves into finer parts. They break down 43 tones in an octave rather than the standard 12.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTo help delineate so much sound, Simon brought back another old soldier, 81-year-old Roy Halee, who oversaw the star’s classic recordings with Art Garfunkel. Halee has always been alive to the role of space in sound and, so, gives each instrument on Stranger enough definition to create a 3D mix.

Simon also reached out to a key, young electro-dance artist from Italy, Cristiano Crisci, also known as Clap! Clap! Crisci contributed beats in three songs, including Wristband, a cut catchy enough to become Simon’s first pop hit in decades.

Throughout the album, Simon uses hand-claps, surrounding them with instruments like the one-string Indian gopichand and the Peruvian percussion piece the cajon. Rhythm often dominates the songs, as it has on Simon albums dating back to Graceland. It’s ironic that the man responsible for some of the most elegant melodies of the last half century has, for years, downplayed that aspect to assert the primacy of rhythm.

Better than ever

On Simon’s last album, So Beautiful, So What, the lyrics underscored the switch, highlighting phrases like “bop bop a whoa” and “ooh Papa Do which hit like a beat. There’s a humour to it all, a quality which has marked Simon’s work since a pivotal move he made with his aptly-named 2006 album, Surprise. There, he collaborated with Brian Eno, who likewise strives to bend music from everywhere to his own vision. On the albums since, Simon has revealed an exponentially greater wit, much of it focused on the folly of faith, as well as human greed and mortality. In The Afterlife, from his last album, a character dies, only to find a mountain of paperwork awaiting him in the beyond. On the new song Werewolf, Simon writes, “most obits are mixed reviews/life is a lottery, a lotta people lose/the winners, the grinners with money-colored eyes/eat all the nuggets/then order extra fries.”

It’s a far cry from the words he penned for Simon and Garfunkel, which could be precious and aloof. Ironically, Simon’s music also became sexier once he entered his sixth and seventh decades. In those senses, as well as in his will to innovate, Simon has bettered the music that remains the most celebrated of his life. How have he, and parallel adventurers, managed to do so while keeping a solid audience? The greying of the population, the refusal of boomers to cry uncle in the ageing game, as well as the millennials’ awe for their elders’ music, have all enabled this awakening.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAmazingly, Simon, and his contemporaries, don’t even represent the oldest exemplars of the sensibility. Tony Bennett, who will turn 90 in August, revitalised his career – yet again – with his 2014 number-one album collaboration with Lady Gaga, Cheek To Cheek. He didn’t even have to rely solely on a vampiric injection of Gaga’s youth to pull this off. On their smash tour last year, Bennett spent far more time on stage than his co-star, offering phrasing that wasn’t just impeccable but inventive.

When I spoke to Bennett last year he told me that, at 89, “I’m still trying to find myself. I study a lot to become better. All the time, I look ahead.”

The music industry hardly encourages that attitude, calcifying artists in the style that made them famous or, worse, encasing them in ones that worked for other stars. But as the old strategies of the industry prove increasingly irrelevant, it has freed artists to both experiment in styles new to them and to imagine a creative future as long as they draw breath.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.