How a 19th-Century portrait of Abraham Lincoln was later revealed to be a fake

The Library of Congress

The Library of CongressWhile the manipulation of images is increasingly causing concern in an era of deepfakes, it's been happening for centuries – even one of the most iconic photos of Abraham Lincoln was doctored.

In an era of deepfakes and AI-generated imagery, the manipulation of photos is increasingly causing concern. But as Hany Farid, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley who specialises in the analysis of digital images, has written, "We may have the impression that photography can no longer be trusted. From the tabloid magazines to the fashion industry, mainstream media outlets, political campaigns, and the photo hoaxes that land in our email in-boxes, doctored photographs are appearing with a growing frequency and sophistication. The truth is, however, that photography lost its innocence many years ago."

More like this:

- 12 iconic images of defiant women

- The early Soviet images that foreshadowed fake news

- Drowning World: Striking photos of the climate crisis

Arguably, photographers have played around with depictions of 'reality' since the birth of the technology, with many of the earliest pioneers also painters, drawing on both science and art in their images. Yet the photographic portrait has long been seen as one of the most accurate ways of capturing someone's true likeness.

The Library of Congress

The Library of CongressIt was one of the means by which Abraham Lincoln came to power, gaining the US presidency in 1861, just before the emerging discipline became widespread, and using photos to his advantage. Harold Holzer, author of The Lincoln Image, argues that "Lincoln sensed that flattering depictions could be his cosmetic salvation". Although he often made fun of his appearance – after being accused of being two-faced, the politician replied: "If I had another face, do you think I'd wear this one?" – Lincoln was a keen sitter for portraits, posing for more than 120 photos in the last 18 years of his life, according to Holzer.

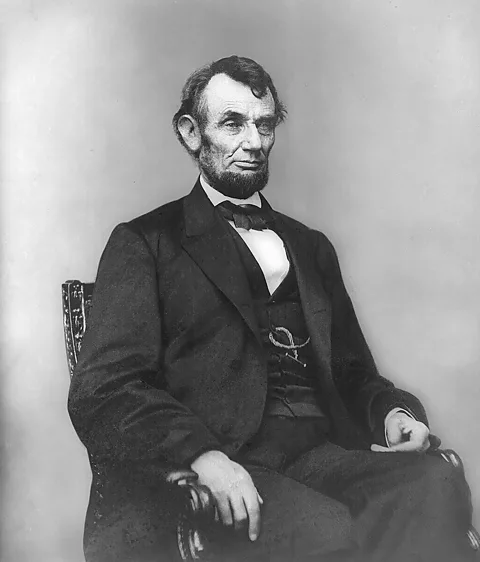

One of those, taken in February 1864 by Anthony Berger, became an iconic photo of Lincoln, used to produce an engraving of the president that adorned the five-dollar bill from 1914 to 2007. Berger was the head photographer at a Washington, DC studio set up by Mathew Brady – one of the first photojournalists in the US, who gained fame for images taken on the Civil War battlefield. As Dr Farid has said, "Brady routinely doctored photographs to create more compelling images".

The Library of Congress

The Library of CongressAccording to The New York Times, former painter Brady "was not averse to certain forms of retouching" – something that happened frequently at the time, as Holzer told Bonnie L Bates of the Civil War Book Review: "It had been done before, but Lincoln and American printmaking more or less came of age together, and the practice grew exponentially during the Civil War. Prints of old Mexican War-era heroes were reissued with new heads; beardless pictures of men like Lincoln, Lee, and Jackson were updated. One publisher in Ohio issued about 50 portraits of Union military heroes, utilising only five or six bodies, on which were grafted interchangeable portraits to meet regional sales demand."

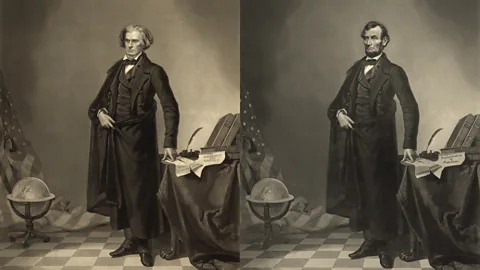

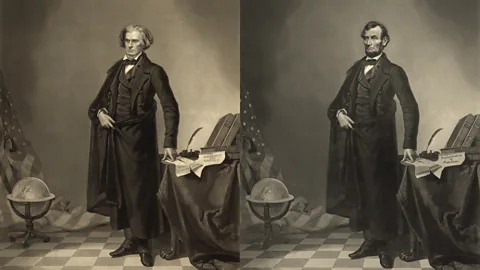

And, aside from gaining a beard, Lincoln did not escape. Around 1865, his head from Berger's 1864 photo was flipped and stitched onto the body of an 1852 engraving by Alexander Ritchie. According to Dr Farid: "In the early part of his career, Southern politician John Calhoun was a strong supporter of slavery. It is ironic, therefore, that the nearly iconic portrait of Abraham Lincoln is a composite of Calhoun’s body and Lincoln's head. It is said that this was done because there was no sufficiently 'heroic-style' portrait of Lincoln available."

The Library of Congress

The Library of CongressPrintmaker William Pate had superimposed Lincoln's head onto Calhoun's body, possibly to give Lincoln a more dignified and patriotic appearance. In the Calhoun image, the papers on the table say "Strict Constitution", "Free Trade", and "the Sovereignty of the States". In the Lincoln composite, the words were changed to read "Constitution", "Union", and "Proclamation of Freedom".

Giving the Union a face – with a slavery defender's body

The contrast couldn't have been starker. As Holzer says, "the John C Calhoun portrait morphed into a Lincoln portrait, flowing robes and all, Unionist replacing secessionist". The Lincoln scholar tells BBC Culture: "The great historical irony is that it's the preserver of the Union's head on the great nullifier's body – the emancipator's face on the body of slavery's most ardent defender."

Perhaps the even greater irony is that Lincoln had embraced portraits as a way of cementing his position, and embedding the Union in the minds of the public. According to The New York Times, "In the early months of his presidency, Lincoln more than tolerated his photographers; he intuitively understood that they were helping him a great deal as he tried to give the Union a face – his own."

Initially, Holzer claims, prints "helped make Lincoln palatable as a candidate, and also transformed him into an icon that symbolised limitless American opportunity – the rail-splitter who had risen to his full potential under our unique system". After he became President, "he changed his image by growing whiskers. Printmakers responded by issuing more avuncular and dignified portraits".

And after Lincoln's assassination in 1865, says Holzer, "there was an explosion of demand for pictures: heroic portraits, deathbed scenes, even retrospective pictures that suggested he was an active military leader". The Lincoln/Calhoun composite was likely created "when demand for images of the martyred Lincoln peaked", Holzer tells BBC Culture.

Holzer believes that the first person to reveal the image was a composite was the late Library of Congress archivist Milton Kaplan, in a 1970 scholarly article for the Winterthur portfolio called Heads of State.

This, and other prints of Lincoln, "elevated Lincoln to the status of American deity", says Holzer. "We know how highly Americans regarded these seemingly primitive pictures. They placed them in the most sacred spots in their homes: above the mantel in the parlour."

Ultimately, then, Lincoln might have had the last laugh – remembered as a hero of the Union in part thanks to the body of a slavery proponent.

If you liked this story,sign up for The Essential List newsletter– a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.