Surprised by a giant jellyfish

Dan Abbott

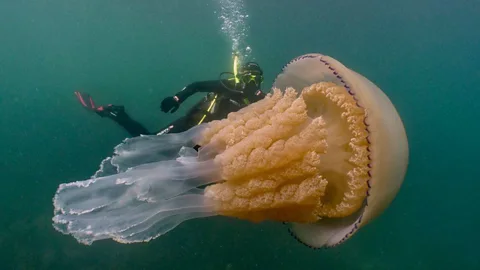

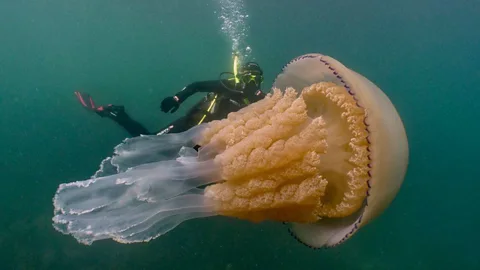

Dan AbbottAfter photos of two divers unexpectedly encountering a barrel jellyfish in Cornwall went viral, Kelly Grovier looks at how creatures of the deep still astonish.

In the Frame

Kelly Grovier takes a photo from the news and likens it to a great work of art.

Nothing underscores the otherworldliness of the sea quite like the jellyfish. Balletic in its strange clench-and-flex propulsion through water, a jellyfish’s alien parachute appears impervious to the laws of motion as it flits and glides. One can only imagine how dislocating it must have been for a pair of divers off the coast of Cornwall in the UK this week to turn suddenly from examining slippery fronds of kelp to find themselves floating face-to-face with a ginormous tentacled sea medusa.

Dan Abbott

Dan AbbottThe two divers, Dan Abbott and Lizzie Daly, were filming a series of aquatic experiences for a social-media fundraising project, Wild Ocean Week, when the unexpected encounter occurred. A photo (taken by Abbott) of Daly swimming alongside the outsized jellyfish quickly went viral. What’s so striking about the image isn’t only the scale of the sea creature, but the collision of worlds that the photo poignantly captures. The clash of textures between the fully wet-suited and snorkel-sucking Daly, rubber masked and artificially finned, and the fragile beauty and effortless grace of the diaphanous sea beast, accentuates how near yet distant our existence is from those with whom we share our world.

Dan Abbott

Dan AbbottStill, even in the strangest of shapes and those furthest removed from our own experience, we are capable of glimpsing a semblance of ourselves. “A jellyfish, if you watch it long enough,” the writer Ali Benjamin memorably opens her children’s novel The Thing About Jellyfish, “begins to look like a heart beating … It’s their pulse, the way they contract swiftly, then release. Like a ghost heart – a heart you can see right through, right into some other world where everything you ever lost has gone to hide.” Ingenious shapeshifters (some are known to morph in order to fool predators), jellyfish are like living lava lamps or fluttering Rorschach tests; the way we perceive their almost amorphousness says more about who we are than what they are. They’re the abstract art of the ocean.

Wikimedia

WikimediaAbbott’s photo, which draws us into its mystery, recalls the power of a late painting by J M W Turner, Sunrise with Sea Monsters. Unknown to scholars until half a century after Turner’s death in 1851, when it was discovered by chance in the basement of London’s National Gallery in 1906, the large oil-on-canvas pulsates with the same pink golds and luminous peachiness vibrating from the jumbo jellyfish that Daly and Abbot encountered.

Anticipating non-figurative art of the ensuing century, Turner’s unfinished painting dares observers to be certain of what, exactly, it is they think they see, struggling to take form amid so much muscular light. Critics remain divided over whether the turbulent dawn depicted by the artist is alive with mythic dragons, with workaday fish, or with anything other than sloshing waves designed to churn up the imagination. Or perhaps, like the jellyfish itself, Turner’s painting is a pulsing mirror in which we perceive who and how we are as we squidge across the universe: joyous or scared, lost or found, imperilled or free.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.