Plans aim to support men before it is too late

BBC

BBCThe government has published its first men's health strategy, with plans to halve the gap in life expectancy between the richest and poorest regions. It says it wants to help men to take charge of their physical and mental health - but what's the picture like in north-east England?

John is diabetic. Despite this, he avoided seeing a GP for 40 years after a bad experience.

"It was trying to explain something to the doctor, but he didn't listen. And I couldn't understand what he was saying," John, who lives in Blyth, Northumberland, says.

He says he lost his temper and vowed he would never go back.

"I have survived without going until the last five years, when I lost my legs," he says.

Men in the most deprived areas die 10 years earlier on average than those in the wealthiest areas, the government says, with Health Secretary Wes Streeting saying "men's health has been neglected for too long".

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the average life expectancy of men in the North East between 2021 and 2023 was 77 years, compared with 81 for women.

ONS statistics also show that last year, more men in the North East were recorded to have died from cancer (4,193) compared with women (3,767), and 67% are overweight or obese, compared with 61% of women.

The new men's health strategy highlights that men are also more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviours including alcoholism, problem gambling and drug addiction.

Although mental health issues are more common in women, one in five men are still diagnosed with depression or anxiety and suicide is the biggest cause of death in men under the age of 50.

Gordon, also from Blyth, says he avoided asking for help with his mental health until he reached crisis.

"I had a bit of an issue a few years ago, I burnt myself out," he says. "I was really working myself too hard and I ended up putting myself three days in the Freeman Hospital [in Newcastle]."

The 64-year-old says he is now more attentive with his health.

"To me that was a wake-up call, I didn't want to go back to the Freeman Hospital again."

In designing plans for men's health, the government gathered evidence from men, experts, charities and campaigners.

The resulting strategy aims to encourage men to "take charge of their own physical and mental health" and improve access to support services.

It also aims to challenge societal norms and stigmas, "so that every man feels empowered to reach out for help".

The strategy talks about the need to "meet men where they are - in their communities, workplaces and everyday lives".

This includes places like football stadiums on match days, by working with the Premier League.

The strategy details a number of new initiatives, including investing £3m over three years in community-based men's health programmes to reach those least likely to ask for help.

The Marine Medical Group in Blyth already runs weekly drop-in sessions away from the doctor's surgery, alternating between a local theatre and the High Street.

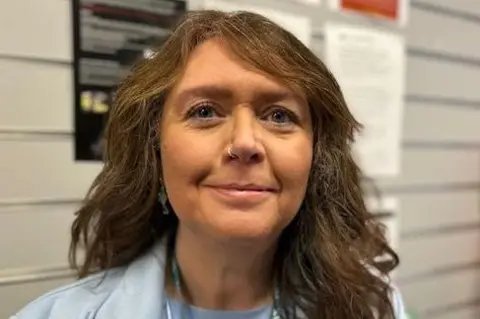

Janey D'arcy is one of the professionals staffing the centre.

She is a social prescriber, helping to connect people to activities, groups, and services in their community to meet their needs.

Men are the most reluctant to come for help, she says.

"We see men when they've reached crisis point. They put it off and put it off."

When Mrs D'arcy asks men why they have left it so long, she says they tell her "there's a stigma".

"It's embarrassment," she says. "Or they're not sure of what will happen at an appointment."

She now helps people understand medical letters they receive, and explains what might happen at routine screening tests or examinations.

DHSC

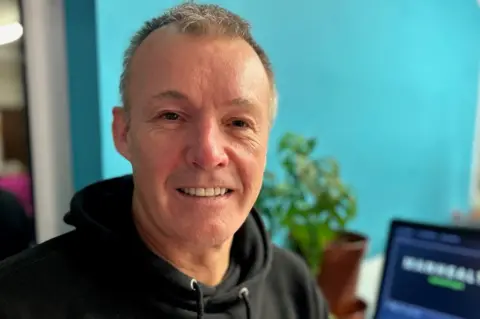

DHSCPaul Galdas, professor of men's health at York University, wrote the foreword to the strategy, and has been tasked with monitoring its success in its first year.

He says it is not always about doing new things.

"It's about organisations stepping up to the plate and doing things differently. It's about considering whether men's needs are being met.

"And it's about giving permission for workplaces to think, what are we doing to support the men in our organisation?"

Prof Galdas says the benefits of getting it right could benefit the whole society.

"Having healthier men means healthier workplaces. It means healthier families. It leads to more resilient communities."

But he say the strategy is just the beginning.

"If it goes on the shelf and it gathers dust and no action is taken, then we won't have achieved what we've been working towards for a number of years."

The strategy calls on the voluntary and private sector to continue supporting men, and pioneer new approaches.

But one voluntary organisation that has been supporting men across the North East for the past decade says future funding will be key.

Just this month, County Durham-based ManHealth announced it would have to stop providing its peer support sessions, citing "relentless financial pressures" and the cost of living crisis.

In an open letter to stakeholders, chief executive Paul Bannister said: "We are ending our groups not because the need has gone, but because of the complete apathy towards men's issues in our society."

Mr Bannister said thousands of men had attended the groups, and that they "do save lives on a weekly basis".

While he welcomed the government's strategy, he said £3m for community groups over the next three years was "not a great deal".

"These community groups are where the magic happens. That money is not enough to fund these groups that make a real difference to men's lives."