How the Irish border was created

PRONI - The Deputy Keeper of the Records

PRONI - The Deputy Keeper of the RecordsIt is 100 years since the final decision was made on exactly where the border would divide the island of Ireland.

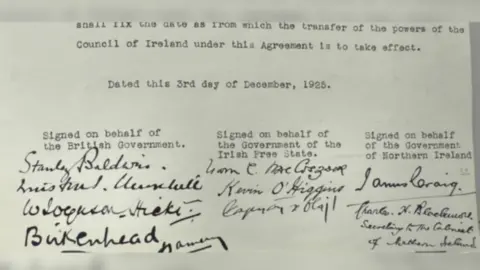

On 3 December 1925 the Boundary Commission plan to adjust the border and take some places out of Northern Ireland, including Crossmaglen in south Armagh, was ditched in a British-Irish deal.

Instead the border stayed the same, much to the relief of unionists and annoyance of nationalists who had hoped counties Fermanagh and Tyrone, plus Londonderry and Newry, would be transferred south.

"It gave of lot of certainty that had not been there before, particularly if you lived on the border and you were living in Fermanagh or Tyrone… you were not sure up until late 1925 that you were going to be in Northern Ireland or the Free State," said historian Dr Cormac Moore.

Southern Ireland was known as the Free State before it became the Republic of Ireland.

Border Timeline

The ditching of the Boundary Commission report in 1925 brought to a conclusion a frenetic period in Irish history which included the partition of the island:

- December 1920: Government of Ireland Act devised a Northern and Southern Ireland

- June 1921: Northern Ireland parliament was established

- December 1921: Anglo-Irish Treaty devised the Irish Free State

- December 1925: Irish border confirmed

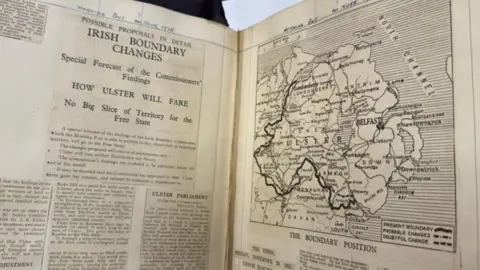

Nationalists had hoped the border drawn in 1920 would only be temporary and that a Boundary Commission agreed as part of the Anglo-Irish Treaty would significantly reduce the size of Northern Ireland.

In the end, it proposed only minor changes and they were never implemented.

Boundary Commission plan

PRONI - The Deputy Keeper of the Records

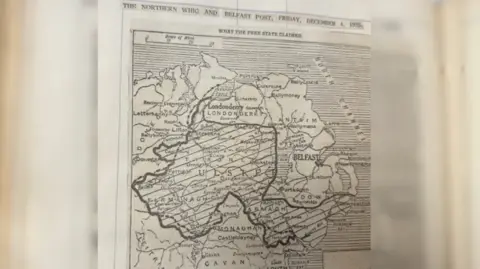

PRONI - The Deputy Keeper of the RecordsThe Irish border stretches 310 miles and the Boundary Commission plan included:

- Transferring parts of east Donegal into Northern Ireland

- Relocating parts of south Armagh to the Free State

- Transferring part of north Monaghan to Northern Ireland

- Relocating small parts of Tyrone and Fermanagh to the Free State

Dr Moore, who wrote a book about the Boundary Commission, said: "The biggest area that was going to be transferred was south Armagh, and it would have included Crossmaglen.

"About 15,000 people would have been transferred to the Free State."

The plan unravelled after it was leaked in the Morning Post newspaper in November 1925.

The Dublin government was angry about the proposals and, after crisis talks, the plan was ditched in a deal involving political leaders from London and Belfast.

However, the Irish government did not gain any land out of the agreement, it only benefited financially.

PRONI - The Deputy Keeper of the Records

PRONI - The Deputy Keeper of the RecordsMoney not land

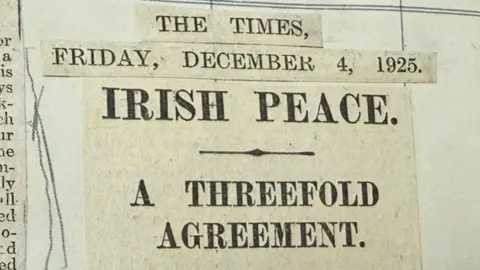

The day after the deal on 3 December 1925, The Times newspaper had three headlines on the outcome: 'Irish Peace', 'A Threefold Agreement' and 'Present Boundary To Stand'.

It was agreed that Dublin no longer had to pay towards Britain's public debt, which had been promised in the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Dr Moore said: "It could have been in the region of £150m, which was a lot of money back then.

"Northern nationalists believed they were sold out by the Free State… abandoned for money essentially."

PRONI - The Deputy Keeper of the Records

PRONI - The Deputy Keeper of the RecordsWho was on the Boundary Commission?

The Boundary Commission was chaired by South African judge Richard Feetham, and on behalf of the Irish Free State government, Education Minister Eoin MacNeill was appointed.

The Northern Ireland government refused to nominate a representative, but the person appointed had deep unionist sympathies, Joseph Fisher, a former newspaper editor.

For nationalists, the Boundary Commission was seen as a missed opportunity.

There has been heavy criticism over the years over how MacNeill performed as the Irish commissioner, and how the then leader of the Free State, WT Cosgrave, handled the aftermath.

The deaths of Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith in 1922 meant Ireland lacked politicians experienced at negotiating with Britain.

For unionists, the securing of the border, not conceding an inch, was seen as a triumph.

Many of the documents and newspapers from the time have been kept by the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI).