Trump wants Venezuela's oil. Will his plan work?

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesDonald Trump has vowed to tap into Venezuela's oil reserves after seizing President Nicolás Maduro and saying the US will "run" the country until a "safe" transition.

The US president wants American oil firms to pile billions of dollars into the South American country, which has the largest crude oil reserves on the planet, to mobilise the largely untapped resource.

He said US companies will fix Venezuela's "badly broken" oil infrastructure and "start making money for the country".

But experts warned of huge challenges with Trump's plan, saying it would cost billions and take up to a decade to produce a meaningful uplift in oil output.

So can the US really take control of Venezuela's oil reserves? And will Trump's plan work?

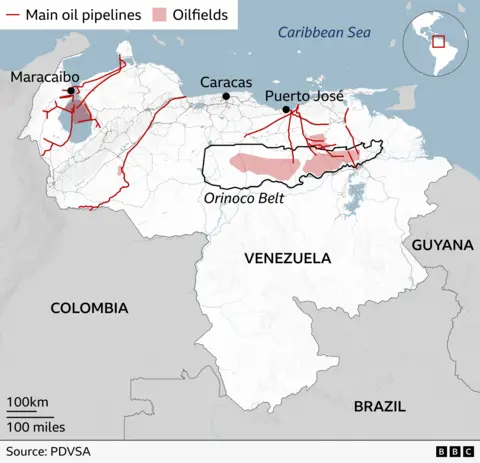

With an estimated 303 billion barrels, Venezuela is home to the world's largest proven oil reserves.

But the amount of oil the country actually produces today is tiny by comparison.

Output has dropped off sharply since the early 2000s, as former President Hugo Chavez and then the Maduro administration tightened control over the state-run oil company, PDVSA, leading to an exodus of more experienced staff.

Though some Western oil firms, including the US company Chevron, are still active in the country, their operations have shrunk significantly as the US has widened sanctions and targeted oil exports, aiming to curb Maduro's access to a key economic lifeline.

Sanctions - which the US first put in place in 2015 during President Barack Obama's administration over alleged human rights violations - have also left the country largely cut off from the investment and the parts it needs.

"The real challenge they've got is their infrastructure," said Callum Macpherson, head of commodities at Investec.

Bill Farren Price, senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, told the BBC that Venezuela's oil industry "had its heyday decades ago" and has been in sharp decline over the past 20 years.

"A lot of the complex supply chain and infrastructure's been looted and taken apart and sold," he added.

In November, Venezuela produced an estimated 860,000 barrels per day, according to the latest oil market report from the International Energy Agency.

That is barely a third of what it was 10 years ago and accounts for less than 1% of world oil consumption.

The country's oil reserves are made up of so-called "heavy, sour" oil. It is harder to refine, but useful for making diesel and asphalt. The US typically produces "light, sweet" oil used to make petrol.

In the run-up to the strikes and capture of Maduro, the US also seized two oil tankers off the coast of Venezuela, as well as ordering a blockade of sanctioned tankers entering and leaving the country.

Homayoun Falakshahi, senior commodity analyst at data platform Kpler, says the key hurdles for oil firms hoping to exploit Venezuelan reserves are legal and political.

Speaking to the BBC, he said those hoping to drill in Venezuela would need an agreement with the government, which will not be possible until Maduro's successor is in place.

Companies would then be left gambling billions of investment on the stability of a future Venezuelan government, Mr Falakshahi added.

"Even if the political situation is stable, it's a process that takes months," he said. Companies hoping to take advantage of Trump's plan would need to sign contracts with the new government when it is in place, before beginning the process of ramping up investment in infrastructure in Venezuela.

Analysts have also warned it would take tens of billions of dollars - and potentially a decade - to restore Venezuela's former output.

Neil Shearing, group chief economist at Capital Economics, said Trump's plans would have a limited impact on the global supply, and therefore price, of oil.

He said there are "an enormous number of hurdles to overcome and the timeframe of what is going to happen is so long" that oil prices in 2026 would likely see little change.

Mr Shearing said firms would not invest until a stable government is in place in Venezuela, and the projects would not deliver for "many, many years".

"The issue has always been decades of underinvestment, mismanagement and it is really expensive to extract," he said.

He added that even if the country could return to previous production levels of around three million barrels per day, it would still be outside the world's top 10 producers.

And Mr Shearing pointed to high production among Opec+ countries, saying the world is currently "not suffering from a shortage of oil".

The former chief executive of BP, Lord Browne, told the BBC that reviving Venezuela's oil industry was a "very long term project".

"People underestimate the time it takes to do things. Marshalling all the resources, the material and people in particular, takes a very long time."

While there might be a "quick pick up" of some production, he added, output might actually fall while the industry is reorganising.

Chevron is the only American oil producer still active in Venezuela, after receiving a licence under former President Joe Biden in 2022 to operate, despite US sanctions.

The company, currently responsible for around a fifth of Venezuelan oil extraction, said it is focused on the safety of its employees and is complying "with all relevant laws and regulations".

Other major oil firms have been publicly silent on the plans so far, with only Chevron addressing the situation.

But Mr Falakshahi said oil bosses will be in talks internally about whether to take advantage of the opportunity.

He added: "The appetite to go somewhere is linked to two main factors, the political situation and the resources on the ground."

Oil firms may be reluctant to return to Venezuela given their previous experiences. ExxonMobil and ConocoPhilips are still seeking billions in compensation from Venezuela after their assets were expropriated in the 2000s.

However, despite the hugely uncertain political situation, Mr Falakshahi said "the potential prize may be deemed too big to avoid".

Lord Browne said companies would want to get involved because "having options for business in different parts of the world is a good thing to have".

"As a piece of business, if you were running a company... you want to get involved very quickly".