Meet the man helping families ahead of the Nottingham attacks inquiry

BBC

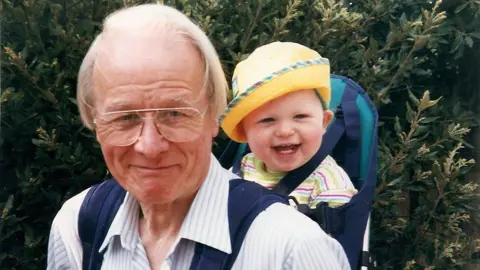

BBCA man who set up a charity after his father was killed by a mentally ill stranger has now overseen hundreds of similar cases ahead of a public inquiry - as he bids to ensure his dad is not "just a statistic".

In April 2007, Julian Hendy's father, Philip Hendy, 67, was stabbed to death in an unprovoked attack by a man with psychosis outside a newsagents in Bristol.

Three years later, Julian founded Hundred Families, with the aim of reducing the number of mental health-related killings in the UK, and to help other people affected.

Now, nearly two decades on from his father's death, Julian is now helping affected families ahead of the Nottingham attacks public inquiry, which is due to begin hearing evidence in London on 23 February. He hopes it will lead to more accountability, transparency and openness about patients who pose a danger to others.

The inquiry has been prompted by a number of damning reviews following the death of students Barnaby Webber and Grace O'Malley-Kumar, both 19, and Ian Coates, 65, who were killed by Valdo Calocane, who also seriously injured Wayne Birkett, Sharon Miller and Marcin Gawronski in Nottingham on 13 June 2023.

Julian is supporting 12 families as part of the Nottingham Inquiry, which will begin hearing evidence from 23 February.

The mental health homicide campaigner, from Leeds, said: "The current situation is unacceptable, families are being failed every day, services are being failed every day, we need to do much better than this."

In addition to documenting 2,426 mental health-related homicides in the UK, Julian's charity has directly supported about 300 families since it was founded in 2010.

This includes the bereaved families of the Nottingham attacks victims who, along with the survivors, campaigned for a public inquiry that was confirmed by Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer last year.

Julian, now 67, said: "To my knowledge, there's never been a public inquiry into mental health-related killings in the UK before."

The inquiry is separate to another major investigation, The Lampard Inquiry, which is concentrating on deaths among mental health inpatients in Essex between 2000 and 2023.

The Nottingham Inquiry will scrutinise killings by mental health patients in the community for the first time in this country.

Chaired by retired judge Her Honour Deborah Taylor, the Nottingham Inquiry will undertake an independent assessment of the events leading up to the killings and provide recommendations to prevent similar incidents from happening.

The victims' families had expressed anger over their case when killer Calocane was sentenced to a hospital order in January 2024, which sparked a number of reviews that identified failings or criticisms of authorities such as the police, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the NHS.

Calocane had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia before the attacks and was assessed by several psychiatrists, leading the CPS to accept his pleas of manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility.

Barnaby's mother Emma claimed the CPS had presented her family with "a fait accompli that the decision had been made to accept manslaughter charges".

"At no point were we given any indication that this could conclude in anything other than murder," she said at the time.

Julian said there needed to be more openness and transparency.

"It's not right that doctors are making decisions about whether people should go to prison or hospital or not," he added.

Supplied

SuppliedThe Hundred Families office, which is at Julian's home, is stacked with dozens of case files - and behind each file is a story of a family affected by a mental health killing.

Julian first started documenting mental health homicides in the UK after his father was killed.

"I couldn't tell whether I was just unlucky or whether it was happening all the time, and I asked people and nobody could tell me," he said.

He was an investigative journalist with Yorkshire Television at the time he began collecting evidence on cases.

His data went back to 1993, when the government first ordered NHS trusts to commission inquiry reports following mental health-related homicides.

He said: "When I started, I just felt that so much was wrong on lots and lots of different levels."

Since then, 2,246 separate cases have been logged by the charity, which amounts to more than 100 mental health killings per year in the UK.

"The mental health trusts are saying 'this is so rare', well it isn't rare," Julian said.

"Time and time again, we see the same things happening, little evidence that people are actually learning from these terrible cases and unfortunately these cases are continuing."

Supplied

SuppliedOne of the trends Hundred Families say it has found is a lack of transparency when it comes to dealing with mentally ill patients who pose a danger.

After a mental health-related killing, bereaved families are given a report by the NHS about the perpetrator's case, but Julian said they were too often heavily redacted.

"It's not acceptable to send families reports that are so redacted, out of consideration for the welfare of the offender," he said.

"It's all too secretive, it's all too covered up.

"I'm staggered by the amount of pushback that there is from psychiatrists for anything that helps victims, and that needs to change.

"There needs to be a big cultural shift in psychiatry to help victims and I'm going to do everything I can to try and make that happen."

Julian believes if a mentally ill person kills somebody, there is a public interest in knowing how well they were managed, so patient confidentiality would not apply, he said.

In the Nottingham attacks case, NHS England initially tried to publish the executive summary, out of concerns for Calocane's patient confidentiality, until the families complained and the highly critical full report was published.

"Why can't we have the full report for all these cases? Because it leads to openness and transparency," Julian said.

He added he was hopeful evidence heard at the Nottingham Inquiry would lead to strong and robust recommendations, to make sure mental health patients were properly looked after and that the public were safe.

"Most people with mental health problems are never violent, but there are some who definitely are," Julian said.

"I don't want my dad to be a statistic, my dad's death meant something and it should lead to change and that's why I hope that we can, with all the families, lead to some changes and some improvement."

Follow BBC Nottingham on Facebook, on X, or on Instagram. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk or via WhatsApp on 0808 100 2210.