Should stolen Shakespeare folio be repaired?

BBC

BBCIf something is broken you should fix it, right?

Especially if it is one of the most beloved books on the planet?

"It's not that simple," Tony King says with a smile.

The First Folio of William Shakespeare's work Durham University got back in 2010 was not the same as when it had been stolen 12 years previously.

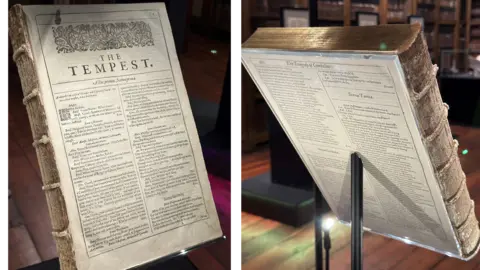

The 400-year-old book had been stripped of its leather cover, boards and end papers.

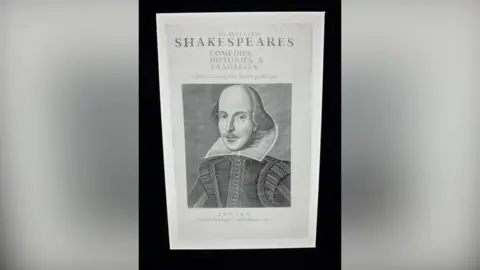

The title page sporting an engraving of the playwright was gone, as were a eulogy by Ben Johnson and the final leaf of Cymbeline, the last of the tome's 36 plays.

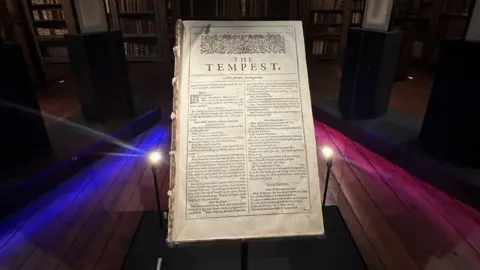

The book on show at Palace Green Library in Durham is naked in its glass case, flanked by half a dozen of its loose pages in separate display panels.

It has been deliberately left in its exposed state - for now.

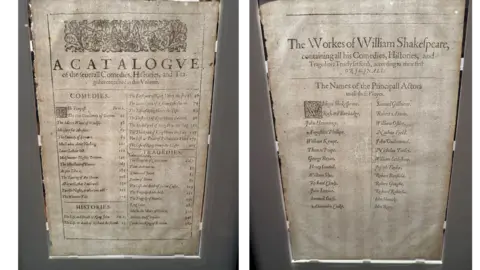

The First Folio was the first collected edition of Shakespeare's plays.

"Almost every single other First Folio is in great condition," King, the university library's senior collection care conservation manager, says.

"This makes Durham's unique and while we would never have wanted it to be unique in this way, let's explore that before we make it like all the others," he adds.

The fact they have it at all is something of a miracle.

An unknown thief had prised open its display cabinet in the library and taken it in 1998, also stealing six other antique books, which have never been recovered.

The book remained missing for 10 years before Raymond Scott, a charismatic raconteur who posed as an international millionaire while living with his mother in Washington, Sunderland, walked into the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC and tried to sell it.

He claimed it had been passed down through the family of a friend in Cuba, but experts quickly identified it as Durham's stolen folio and he was subsequently jailed for eight years after being found guilty of handling stolen goods.

Scott, who always maintained his innocence and became something of a sensation through his colourful court appearances - arriving in horse drawn carriages or stretch limousines while clutching a Pot Noodle - took his own life in prison in 2012.

It has never been proven who stole it but in his book Shakespeare & Love, journalist Mike Kelly, who got to know Scott well, reckons the 55-year-old did it.

Several times Scott described stealing it to Kelly, before backtracking and calling his accounts a "fairy story" or "lies and jest", the author recounts.

"I am as certain as I can be that he did steal the Shakespeare First Folio," Kelly writes, citing £90,000 debts and Scott's desire to woo a Cuban dancer he was smitten with as reasons for his subsequent ill-fated attempt to sell the book.

When the book was returned to Durham, the initial reaction was to repair the damage, King says.

"It had been vandalised recently, repairing it seemed the logical route to take," he says.

But rebinding a book is an "inherently destructive" process, he adds, likening it to having to replace a skeleton.

Book conservator Lauren Moon-Schott nods in agreement.

"To return it to a traditional-looking book would have required actually stripping away a lot," she says.

Some work was done to it to get it to a stable condition, but full restoration would have been a big job.

In 2010, the university's focus was on preparing for other major exhibitions so, after briefly being exhibited to celebrate its return, the book went into storage until it was put on its current display in April 2025.

Many of the staff from the time of its theft and return have gone, with the new generation having "a bit of detachment from that really quite traumatic experience", King says.

The conservation conversation is now different, Moon-Schott adds.

"We started exploring what is unique about this book, what can we make of this book in this current condition.

"And that's when we started seeing all these really interesting opportunities for it."

Its damaged condition actually offered scope for analysis which would not be viable with more intact copies, while for members of the public wanting to view it on display, the denuded folio could be seen in a whole new light.

"When you walk in and see that vandalised masterpiece, that has an effect on people," King says.

Normally when one of the world's 235 First Folios is put in display, it is fixed open at the portrait page, assistant curator David Wright says.

So visitors to the award-winning Durham exhibition, which runs until April, are "seeing more of this iconic book than anywhere else in the world", he adds.

Guests are asked what they think should happen to it next - to rebind or not to rebind, that is the question.

Surprisingly perhaps, the majority say they are in favour of leaving it as it is.

"But at the same time, there is a sizeable number advocating for the rebinding," Wright says, with both "perfectly valid options".

He adds: "One of the things that's been really amazing is how much thought visitors have put into that question, it's given us so much to think about really."

The Durham folio was already unusual in that it had essentially been in the same ownership since it was printed in 1623.

Bishop John Cosin bought it when it was new and put it in his library, which later became part of the university.

It has undergone alterations previously, the cover torn off after its theft had been put on in the Victorian era.

"You might think it was perfect when it was made, but it was never perfect," King says. "That's not a very helpful concept.

"It's always been altered, sometimes it's better, sometimes it's worse."

A decision on what to do with the book will be made in three years, after a long period of consultation and reflection.

"Conservation is always seen as a restoration, returning things to this perfect state, this former glory," King says.

"But we're not about making things looking pretty and beautiful again, it's about preserving what makes them unique."

It would be a "different discussion" if this was the only one of the 750 or so First Folios thought to have been printed, King says, but the damage is now a part of its history.

Moon-Schott agrees, adding it could be made to "look nice and new", but they could "never undo the fact it was a vandalised book".

The question, King says, is how much time has to pass before that history becomes important and worthy of preservation?

The answer, Lauren says, is "time will tell".

Not that simple indeed.