Could studying river sewage improve global health?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe fact that antibiotic-resistant bacteria has recently been found in the river system comes as no surprise.

A study in 2015 found evidence in the River Thames, with higher concentrations near sewage plant outfalls.

And in February, a new study found widespread traces of antibiotic‑resistant bacteria in Oxford's river systems, prompting calls for year‑round water sampling.

However, little is known still of just how high the level of risk this poses to public health - in particular to people who use our waterways for recreational purposes - which is of concern to anti-pollution campaigners in the UK.

Global health threat

What is accepted by scientists is that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the top global public health threats, and antibiotic resistance is a form of AMR.

Antimicrobials include antibiotics, antivirals and anti-fungals.

They are medicines used to prevent and treat infections and diseases in humans, animals and plants.

Resistance occurs over time through genetic changes, a form of evolution - survival of the fittest - and, according to the NHS, is accelerated by the inappropriate use of antimicrobial drugs, poor infection prevention, a lack of new antimicrobial drugs being developed as well as insufficient global surveillance of infection rates.

The result being that bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites no longer respond to antimicrobial medicines; the treatments become ineffective, and so there's an increased risk of diseases spreading, severe illness, disability and death.

According to a report published in 2025 by the National Audit Office, AMR contributes to nearly 5m deaths a year globally.

In the UK, it contributes to more than an estimated 35,000 deaths and directly responsible for 7,600 fatalities.

Scientists say there are few alternatives available, and so we rely on antimicrobial medicines to treat illnesses such as TB, urinary tract infections, chest infections and food poisoning.

They are also used to prevent infections after routine procedures such as hip and knee replacements.

Is sewage the answer?

So why are scientists, who are studying AMR, interested in sewage treatment works and their outfalls?

Answer: They have big concentrations of different antimicrobial bacteria.

From the chemicals we use in our kitchens to eliminate germs, the anti-dandruff shampoo we use in the shower which can be anti-fungal, to the medicines that go through our bodies and are flushed down the loo.

They all end up at the sewage works.

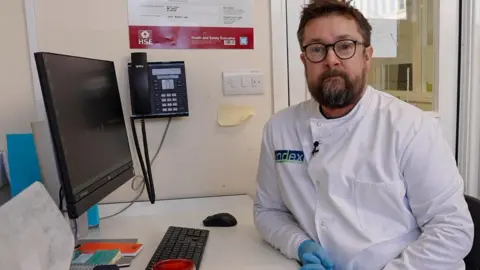

Dr Rob Morley, Director of Index Microbiology, who led the recent research in Oxford, said: "There's a potential for these bacteria to transfer their genes, their genetic make-up. So you could effectively be increasing that reservoir of antimicrobial resistance within the environment."

There are no legal limits of levels of drug-resistant bacteria in sewage plant effluent and water companies aren't required to remove bacteria before discharging into the environment.

In addition, our rivers are not only affected by effluent from sewage works.

Run-off from agricultural and urban areas enter them which might contain medicines given to animals, or pesticides, herbicides and fungicides used on the land, which are all antimicrobials.

The UK Government has a national action plan for tackling antimicrobial resistance and the Environment Agency works with the water industry on a chemical investigation programme.

It is looking at how to monitor AMR in the environment and what to monitor.

It is also trying to understand what concentrations of antimicrobials can drive the development of resistance.

The National Audit Office Report from 2025 says the government spent around £567 million directly on AMR programmes between 2020-21 and 2023-4.

However, it added there has been no sustained reduction in the amount of AMR-related human infections that the government tracks.

The Department for Health and Social Care aimed to reduce human drug‑resistant infections by 10% between 2018 and 2025.

However, by 2023 infections in England had risen to 13% above the 2018 baseline.

Campaigners in Oxfordshire are calling for more action.

They want nationwide, annual, routine testing of waterways to add to the information being collected by scientists and believe it is an issue that needs to be addressed now and not left to future generations.

You can follow BBC Oxfordshire on Facebook, X, or Instagram.