How the age of motoring shaped our modern world

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFifty five years ago, in April 1971, Birmingham welcomed the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh to officially open the city's inner ring road - a symbol of Britain's love affair with the car.

She mistakenly named the full stretch of the route Queensway instead of just the intended tunnel at Great Charles Street, but the moment captured the spirit of an era when roads and motorways were about more than just transport.

"It showed the importance, and the fact the project had the royal seal of approval," said author Christopher Beanland.

His new book explores the architectural impact of the car, and how it transformed the modern world.

In post-World War Two Britain, the car was a way of life, with entire cities redesigned with motorists at heart.

Places like Coventry, Bristol and Glasgow were shaped by planners who believed "we would all be driving and so we would have to have the provision for it," said Beanland.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFuturistic automated car parks, underground bus stations and motorway service stations were built, having been inspired by the motels and drive-throughs of the US and Brutalist architecture of Germany.

The car was indeed king, and nowhere was this more evident than in the West Midlands, home to Britain's booming car industry at the time, Beanland said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlthough now under threat of demolition, Birmingham's Ringway Centre, on Smallbrook Queensway, became a symbol of its time.

A sweeping curved, six-storey office block in the heart of the city, it was a concrete celebration of modernity, he said.

Herbert Manzoni's vision for the city was a series of main routes linked by junctions, traffic islands and tunnels, embracing mass automobility as a sign of progress.

"Manzoni famously - as well as other planners around the Midlands - wanted to build what he believed back then, to be the ideal city," said Beanland.

The opening of Spaghetti Junction and redevelopment of Paradise Circus, topped with John Madin's library brought all of those parts together.

"It really wanted to be seen as the most modern city in Britain."

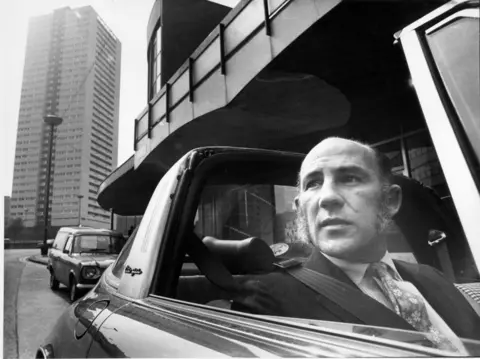

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe city centre, at the time, was seen as cool enough to be a backdrop for Clint Eastwood's visit to the UK promoting his then new movie A Fistful of Dollars.

A film voiced by Kojak actor, Telly Savalas - calling it "my kinda town" - celebrated the city's Aston Expressway and "revolutionary" road systems.

"The modern buildings reflect its position as the nation's industrial powerhouse," he said in the film, adding "you feel as if you've been projected into the 21st Century".

As the centre of Britain's motor industry, Coventry's post-war planners also put the car bang in the middle of its redeveloped city centre, with a distinctive circular car park.

"They thought why not have the ability to drive all the way, not just into the city, but right to the market, park on the roof, then you could go down and shop," Beanland explained.

"That was the kind of thinking we had back then - everything designed for the convenience of drivers."

But that convenience came at a cost for pedestrians, and the communities displaced to make way for this car-centric world, he said.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I certainly wouldn't be defending things like knocking down whole parts of the city and demolishing homes and communities," he added.

"But I think we can still see there's some really interesting ideas that went on, and, it's a really fascinating part of our history, and should be preserved."

Aaron Law

Aaron Law"One of the things I wanted to do in the book is draw people's eyes to the things we see every day and maybe take for granted," Beanland said.

"Things like amazing motorway services, petrol stations and car parks, motorways and ring roads.

"I think every town and city in the Midlands got a ring road, including Stourbridge, Wolverhampton and Walsall."

These roads and motorways were a "source of pride," he added, "they wanted to have nice roads that you could drive your Morris Marina on and explore the city".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPeople sometimes viewed these changes as "a bit brutalist, very functional and a bit inhuman," he said.

"But what I found when I was investigating the subject is there was a lot of care and attention that went into these schemes in terms of public artworks," added the author.

The city's profusion of underpasses provided the ideal backdrops.

"Huge concrete Aztec-looking" sculptures by artist William Mitchell were commissioned for Hockley Circus beneath the flyover, later given listed status recognising their importance.

Artist Kenneth Budd also created murals for Colmore Circus, as part of the inner ring road, as well as a JF Kennedy memorial mosaic.

"The history of public art in the age of cars is a story worth telling," he added.

Monaco of the Midlands

Getty Images

Getty Images"An interesting postscript to the story of Birmingham as a motor city was the Super Prix," he said, "when parts of the middle ring road were made into a racetrack.".

The Formula 3000 event attracted crowds of thousands when it was staged in the city between 1986 and 1990.

"It sounds absolutely bonkers," Beanland added.

An early supporter of the scheme, motor racing legend Sir Stirling Moss was among those calling for its return, before his death in 2020.

A group, backed by the former mayor of the West Midlands, Andy Street, were also calling for it to stage the all-electric Formula E series.

It is yet to be seen whether racing will ever return to the roads of Birmingham.

'Fragments of history'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy the 1980s, car-centric architecture and Birmingham's Brutalist landmarks had fallen out of favour.

A group fighting to save the Ringway Centre lost a bid for a judicial review of plans to demolish the building and replace it with apartment blocks.

The campaign was backed by Extinction Rebellion - an environmental group who ended up trying to help save the city's monument to the car.

Madin's library, once described by the King as looking like "a place where books are incinerated, not kept," was also demolished in 2013, to make way for the new Library of Birmingham.

"A lot of damage was done" creating these cities, said the author, "but it is an important part of our history".

"To knock it all down again is maybe not the answer, because it wastes energy and also destroys these fragments of history that tell us about a different way of thinking when people put the car first".

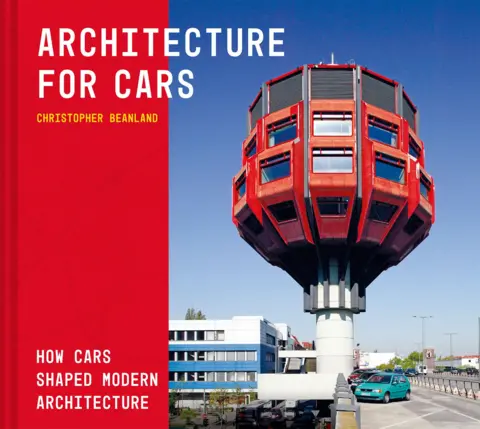

Batsford

BatsfordArchitecture for Cars: How cars shaped modern architecture by Christopher Beanland is published by Batsford.

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, X, and Instagram, Send your story ideas to: [email protected]