Have you got what it takes to go to the Moon?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen the Artemis mission lands on the Moon in years to come, its crew will have to grapple with a challenging environment and extreme isolation. What will it take to thrive in a lonely Moon base?

"Space is really challenging," says Nasa astronaut Victor Glover. "It's harder than it looks, and we don't say that often enough."

I spoke to him just before the Starliner spacecraft's ill-fated mission to the International Space Station (ISS). Later, when the capsule's thruster system failed during docking, the crew was left stuck in space for eight months. Which rather proves Glover's point.

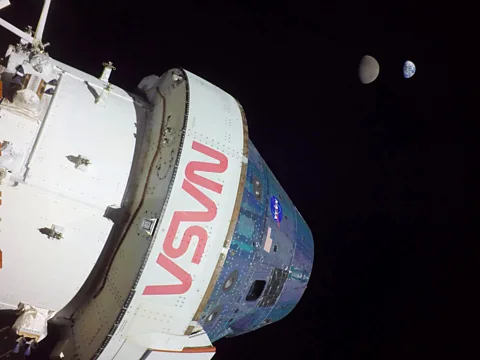

The astronaut will soon take the controls of Artemis II, piloting the first crewed Orion capsule beyond the Moon – further than humans have ever gone before. For 10 days, Glover will live in a small pressurised compartment with his three companions.

He does not take his responsibilities lightly. "We have a tank full of water, and as we drink that water, it's gone," he says. "We have food, and as we eat the food, it's gone – no one's sending a resupply ship."

Even the simplest daily activities will become a challenge, and potential annoyance. "There's no such thing as privacy," he says. "You can go into the waste and hygiene compartment and shut the door and as soon as you flip the machine on, you wake everybody up – it's the loudest thing other than the engine."

"These are the things that are going to require a different set of psychological preparations."

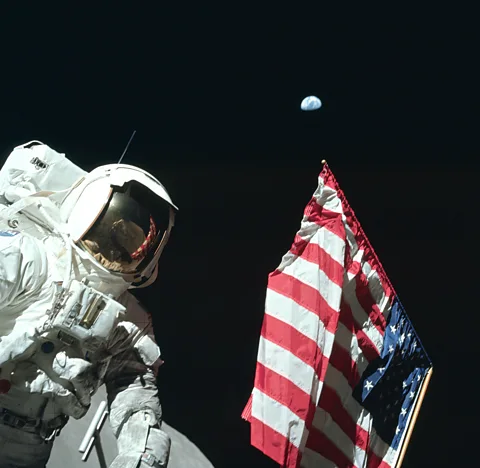

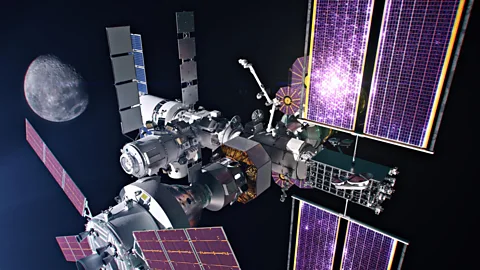

Artemis II is the first step in humanity's eventual return to the Moon. Future US-led missions will land humans on the lunar surface and construct a base near its South Pole. Astronauts will be days away from Earth, living for months in confinement with only their colleagues for company. With nights that last two weeks, outside it will be dusty and airless with extreme temperatures and potentially damaging levels of radiation.

Nasa/ Getty Images

Nasa/ Getty ImagesTrips to the Moon are going to be both physically and mentally demanding, and it's crucial to find the right people for the job.

"It's very difficult to select an astronaut because you're not looking for superhumans in any one domain," says Sergi Vaquer Araujo, who leads the space medicine team at the European Space Agency (Esa) and will help oversee astronaut selection for future lunar missions. "You're looking for someone good in all domains – and that is dramatically difficult to find."

When Nasa selected its first astronauts in the 1950s, the candidates were all test pilots at the peak of physical fitness. During selection, these men (and they were all men) had to endure weeks of tests – covering everything from lung capacity to eyesight, bowel movements to sperm count. Those that emerged were said to have "the right stuff."

Today's astronauts are no longer required to be as exceptionally fit, but they do still need to meet certain physical criteria.

"Any kind of chronic sickness that impedes function during the mission would be disqualifying," says Vaquer Araujo. So, although short-sightedness might be acceptable, lung conditions (such as asthma), heart irregularities or colour blindness can rule out even the best qualified.

"It's important to understand that we're on an exploration mission and we don't have the medical equipment we have on the ground," Vaquer Araujo says. "To reduce risk, we have to have well-screened people – if you had an asthma attack in the middle of the mission then we wouldn't be able to treat that."

While that might rule out many potential candidates (this reporter included), most reasonably fit people have a good chance of passing the physical. But that is only the start of what the "right stuff" means today. Much of the selection process is about assessing cognitive abilities and psychological suitability for space missions.

The first astronauts were hyper-competitive winners – "alpha males" – ready to put their lives on the line. It made them exciting people to be around but not necessarily spend too much time in a confined space with. Today, being able to work well with others is one of the most important attributes of an astronaut. It is not necessarily an advantage to win.

Nasa

NasaDuring Esa's most recent astronaut selection process, candidates were observed during team challenges. "The success of the team was more important than personal success," says Vaquer Araujo. "It got to the stage where, to succeed, you had to lose for the benefit of the team."

Another way to discover if you have what it takes to make it on the Moon is to try living at the ends of the Earth. British surgeon Nina Purvis has recently returned from the French Italian Concordia research station in Antarctica. Selected as part of an Esa research programme, she spent the whole winter with just 12 other people.

"It's called 'White Mars' because it's an isolated, confined and extreme environment," says Purvis. "During the polar night there's no sunlight and it can reach around -80C (-112F) each day.

"From February to November the station is completely isolated, so we have to be autonomous in terms of food, fuel and medical care," she says. "If somebody gets ill there's me and a more senior doctor in emergency medicine and we would work together to treat any patient."

Fortunately, emergencies at Concordia are rare, and Purvis spent most of her time conducting experiments – some on her companions. As well as research including how gut health fares in an isolated community, several of the studies concerned mental wellbeing. Anyone chosen to work in Antarctica will have undergone a similar selection process to astronauts, so investigating how to improve their mood and resilience can help inform future space missions.

"You have to be a pleasant person to work with, that's number one," Purvis says. "You have to deal with pressure, stress and uncertainty and still be able to perform in your job – you can train for every scenario but something's going to happen that we can't predict."

What has also become apparent from decades of polar research is that while there is occasional excitement, boredom is a serious concern. "There's not much stimulation here in terms of the environment, so it's very monotonous," says Purvis. "You don't want to sit in your room in the dark and watch Netflix all of the time."

One of Purvis's experiments was on mindfulness. Building on previous research, she would gather the crew together for activities that included yoga, Lego construction and painting.

Getty Images

Getty Images"We haven't had all the results yet, but I felt it benefitted me, and the team actually looked forward to doing the activities and they brought them together," Purvis says. "And that's the kind of experiment that has a low payload, but a very high reward and I think they will definitely implement it into astronaut schedules in future."

It's not only space agencies that have been experimenting with Moonbase living. At the height of the Covid pandemic in September 2020 – when many of us were getting fed up with isolating from others – 24-year-old architect Sebastian Aristotelis and his 22-year-old colleague Karl-Johan Sørensen embarked on a mission of their own. Having previously won a competition to design a concept Mars habitat, they decided to build a prototype lunar habitat and live in it for 60 days in northern Greenland.

"We decided we didn't want to do any more of this concept stuff," says Aristotelis. "People already thought we were mad, and I needed to see that we could actually build something to believe that I was not just a crazy dreamer."

More like this:

• Artemis: The return of the Moon that will set space records

• Why there's a rush to explore the Moon's enigmatic South Pole

• The astronaut school inside a Swiss mountain

It was only when they were being dropped off by the Danish Navy that Aristotelis began to have doubts. "I saw the little dot of land in this barren landscape and that was the first time I realised what we had signed up for," he says. "All the cheering and excitement just fizzled out, and it was just this completely quiet moment… feeling nervousness and a little bit of anxiety for the first time."

Built from carbon fibre and covered in solar panels, the prefabricated Lunark Moon base was designed to unfold like origami but had to be strong enough to withstand any polar bear attacks (obviously not an issue on the Moon). Although it was only a couple of metres wide, the habitat was fitted with three interior compartments stacked on top of each other so the companions could have their own private space. An estate agent might describe it as cosy. They also developed an interior lighting system to simulate daylight and keep circadian rhythms in check.

Getty Images

Getty Images"The first day was so claustrophobic, there was so much equipment that we were standing up in this tiny capsule," says Aristotelis. "Then after days of getting settled, we got into a routine and all of a sudden, because outside was so extreme and scary, the inside very quickly became a home."

As a result of the experiment, Aristotelis's business Saga now operates in two continents working for space agencies and companies to design lunar habitats and space station interiors.

"I think about the mission every day," he says. "If you're going to design a house on the Moon, you need to try very hard to get an experience similar to what it would be like with all the small annoyances and problems that you can then find solutions for."

Glover, meanwhile, has spent years training for Nasa's return to the Moon and may one day even find himself living there. I ask him if he is psychologically prepared for leaving Earth so far behind?

"I don't know," he says. "Ask me that when I get back!"

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.