'They've probably been untouched for 49 million years': The New Mexico cave expanding our search for alien life

Lars Behrendt

Lars BehrendtWhen cave biologist Hazel Barton ventured into the pitch darkness, the last thing she expected to find were organisms harnessing energy from light. This new understanding of photosynthesis in the dark, she realised, means life elsewhere in the Universe could exist in places we never thought possible.

"The wall was bright green. It was the most iridescent green you'd ever seen, and yet the microbes were living in complete darkness," says Barton, professor of geological sciences at the University of Alabama.

Beneath the deep rocky canyons of the Chihuahuan Desert in southern New Mexico, lies a network of 119 caves. The caves, part of the Carlsbad Caverns National Park, formed four to 11 million years ago due to sulphuric acid dissolving the limestone rocks.

The primary attraction of the park is the show cave, Carlsbad Cavern. Here, glittering stalactites cling to the roof of the Big Room, a huge underground chamber measuring almost 4,000ft (1,220m) long and 625ft (191m) wide.

"The Carlsbad cavern is very easily accessible. It's a very large limestone cave that tourists can visit that has steps and ladders and everyone can go down," says Lars Behrendt, a microbial biologist at Uppsala University. Parts of the cave system, he adds, are even wheelchair accessible.

Almost 350,000 people visit Carlsbad cavern each year, yet most would be completely unaware that the cave is the setting to one of the most baffling scientific discoveries of the past decade. In the seemingly pitch dark, microbes were able to harness light for energy – the same kind of light given off by red dwarf stars, the most common kind of star in our galaxy. This, says Barton, means we can search for extraterrestrial life in more places than prevously thought.

In 2018, Behrendt had just finished his PhD. He had also won an academic prize, which awarded him some money. He contacted Barton and asked her if she would accompany him on an expedition. Luckily, she agreed.

"The first thing you do in the Carlsbad cave is you kind of go down on the tourist trail, and then you turn around a corner," says Barton. "I don't know how many times I've done that trail, probably 40 times. At that point, you go around the corner, and then behind you there's an alcove, and it's completely black."

For more than 20 years, Barton has been studying microscopic life found deep underground. Yet what happened next was a surprise, even to her.

Behrendt shone a torch on the wall. Although the alcove was pitch black, the light revealed a blanket of green microbes clinging to the wall. Later tests revealed they were cyanobacteria; single celled organisms related to bacteria. Unlike most bacteria, though, cyanobacteria (also known as blue-green algae) use light from the Sun to make food.

Lars Behrendt

Lars Behrendt"We started going deeper and deeper into the cave," says Barton. "Eventually we were a point where we couldn't see without using flashlights. We had to use a headlight to be able to see our hand in front of our face, and yet you could still see green pigment on the wall."

Plants are green due to a chemical called chlorophyll, which absorbs light energy. In photosynthesis, this energy is used to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen. The process is much the same in cyanobacteria. Yet here, in the cave, there was no sunlight.

So what was going on?

It turns out that the cyanobacteria in the cave have a special version of chlorophyll that can capture near-infrared light. This light has a longer wavelength than visible light, and appears just before infrared on the electromagnetic spectrum. It is undetectable to the human eye.

While plants and cyanobacteria use chlorophyll a for photosynthesis, the cyanobacteria in the Carlsbad caves use chlorophyll d and f, which are able to generate energy from near-infrared light.

Although visible light can only travel a few hundred feet into the caves, near-infrared can journey a lot further due to the reflective nature of the limestone rocks. "The limestone rock that the cave is made of will absorb almost all visible light, but to near-infrared light, caves are pretty much a hall of mirrors," says Barton.

In fact, when the researchers measured the light in the back of the cave where it was darkest, they found the levels of near-infrared light were 695 times more concentrated than at the entrance. At the same time, while chlorophyll d and f containing cyanobacteria were present in all parts of the cave, they were particularly concentrated in the darkest and deepest places.

The researchers also hiked out to other caves in the Carlsbad Caverns National Park and tested other off-the-beaten-track caves and caverns. In each case they found photosynthesising microbes deep down underground.

"We showed that not only do they live down there, but that they photosynthesise in a completely sheltered environment where they've probably been untouched for 49 million years," says Behrendt.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBarton and Behrendt aren't the only scientists to find microbes able to live in the dark.

In 1890, pioneering Ukrainian-Russian microbiologist Sergei Nikolaevich Vinogradskii discovered that some microbes could live solely on inorganic matter – using a process called chemosynthesis. These microbes gain energy through chemical reactions, taking chemicals such as methane or hydrogen sulphide from surrounding rocks and water.

In 1996, Hideaki Miyashita, who at the time was a student on Nasa's postdoctoral programme, discovered a marine cyanobacterium named Acaryochloris marina that can photosynthesise using both visible and near-infrared light. This discovery kickstarted decades of research into the wavelengths of light required for photosynthesis.

Then, in 2018, scientists at Imperial College London found photosynthesising cyanobacteria living in shady conditions in bacterial mats in Yellowstone National Park, and inside some beach rocks in Australia. They even managed to grow photosynthesising microbes in a dark cupboard fitted with infrared LEDs. In each case, the cyanobacteria used chlorophyll a to photosynthesise using visible light, but then switched to using chlorophyll f to photosynthesise using near-infrared light – beyond the reach of human vision.

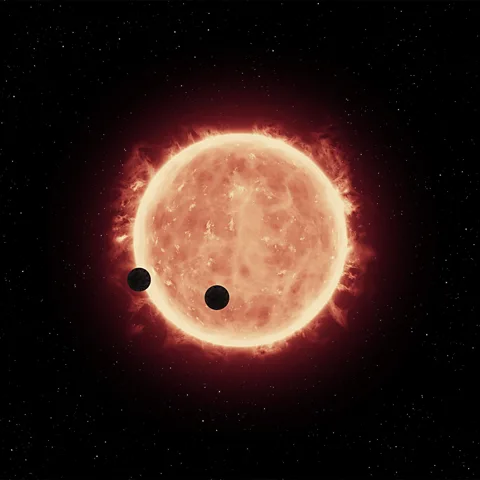

The findings have repercussions for what life on other planets could look like. When looking for a habitable exoplanet – a planet that orbits a star in another solar system – it's important to take into account the type of star that it is orbiting. Astronomers have tried to group stars by the colour of light they produce, resulting in seven classes of stars (O, B, A, F, G, K and M), which are arranged in order of decreasing temperature, from hottest to coolest. O- and B-type stars are the hottest, most massive and most luminous stars in the Universe. They are characterised by their blue-white colour.

"They produce a lot of UV radiation, so they're toxic to life," says Barton.

G-type stars, which include our Sun, are yellow in colour and produce a lot of light in the visible spectrum. These stars would theoretically be good places to look for habitable worlds, but G-type stars constitute just 8% of the estimated one billion trillion stars in the Universe.

By far the most abundant star type to be seen in our galaxy, however, are red dwarfs, or M-type stars. The majority of rocky exoplanets to be discovered to date have been found orbiting this type of star.

Alamy

AlamyAs red dwarfs are low mass stars, their planets tend to orbit closely, which makes them easier to spot. Another reason that M stars have proved so fruitful in scientists' search for exoplanets is because they are so plentiful. However, currently red dwarf stars are thought to have a very narrow habitable zone – the area closest to the star where conditions are neither too hot, nor too cold for liquid water to exist on the planet's surface. (Read more about the epic hunt for a planet just like Earth.)

As the existence of liquid water is essential for life on Earth, this measure, known as the star's "Goldilocks zone", is what astrobiologists have focused on when looking for extraterrestrial life. So far, they have found dozens of candidates. However not all of these planets could sustain life, and directing telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) takes time and considerable resources.

More like this:

• The peculiar smells of outer space

• The scientists looking for alien vegetation

• The scientists venturing into the deep, dark Earth

Another important factor which governs whether life can exist is whether photosynthesis can take place. On Earth, photosynthesis forms the base of most food chains and provides the oxygen we breathe. For this reason, it makes sense to limit the search to planets that can support photosynthesis. This could dramatically reduce the zone around a star where life could exist.

In the past, astrobiologists set the limit for photosynthesis at a wavelength of 700nm in the light spectrum, which is the equivalent wavelength of the colour red. This is the point at which the efficiency of photosynthesis using chlorophyll a declines. However, the cyanobacteria discovered in the Carlsbad cave systems can harvest light up to wavelengths of 780nm using chlorophyll f.

"The vast majority of stars in our galaxy are these M- and K-type stars," says Barton. "This means most of the stars in our galaxy are putting out near-infrared light, and yet we barely know anything about how photosynthesis and life could survive under the conditions of light that would be produced by a star like that."

Nasa, ESA and G. Bacon (STScI

Nasa, ESA and G. Bacon (STScIBarton plans to change this. Together with Behrendt, she has put in a proposal to Nasa to find the limits of where photosynthetic life can survive. The work would involve going deep down into the darkest caves to measure exactly how much light is needed for cyanobacteria to survive. That information can then be used to narrow down the search for habitable worlds. For example, with the JWST, scientists can measure the amount and type of light exoplanets receive.

"What our work is trying to do is figure out what is the longest wavelength of light and lowest level of light at which you can photosynthesise," says Barton.

"Then what you can do is take the 100 billion potential stars that we can point the James Webb Space Telescope at, and reduce it down to say 50 stars [which may host life]."

In other words, it could lead to astrobiologists broadening the types of worlds that they believe could support life. All that would remain would be to point the JWST at the star in question and then look for planets passing in front of it. As the light from the star travels through the atmosphere of the planet, specific frequencies of light are absorbed depending on what elements are present. Astronomers can therefore work out if certain elements which might hint at the presence of life, such as oxygen, are present in the exoplanet's atmosphere by looking for missing lines on the absorption spectra.

"There are very, very few ways that oxygen can be made in an atmosphere without life," says Barton. "So, if you can find the oxygen in the atmosphere of one of those exoplanets, it's a very, very strong marker for potential life."\

* This article has been updated to correct information about the spectral classification of stars from O to M. This article also incorrectly stated that all exoplanets discovered to date have been found around red dwarf stars. Exoplanets have been discovered around a wide variety of stars.

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.