The Ice Man of Ladakh building artificial glaciers in the Himalayas

Kanika Gupta

Kanika GuptaA local inventor is building artificial glaciers in the Himalayas to provide farmers with water for irrigating their crops.

"I remember as a kid, it used to snow a lot, almost as high as my knees," says Dolkar, a 58-year-old potato farmer from Thiksey village in Ladakh, in the north Indian Himalayas. "But now, it doesn't rain or snow so much."

Dolkar hails from generations of potato farmers but has seen her family income dwindle over the years – just like the ice caps on the mountains surrounding her hometown, which lies 19km (11.8 miles) east of Ladakh's capital city of Leh.

"As potato farmers, we used to make up to Rs 70,000 (£700, $892) per month. But now, we make close to Rs 20,000 (£200, $255)."

Receding glaciers

There are 55,000 Himalayan glaciers, encompassing approximately 3 million hectares and representing the largest ice bodies outside the polar caps. However, climate change now threatens to have a severe impact on the fragile Himalayan ecosystem, affecting the economy, ecology and environment of the region. Around a third of the Himalaya's glaciers could vanish by the end of the next century, leading to major changes in Asia's river systems which provide water for about 1.5 billion people. The melting will also impact crop production and the livelihoods of around 129 million farmers who depend on meltwater from these glaciers.

One such region lies in the northern most part of India – Dolkar's home, Ladakh.

Kanika Gupta

Kanika GuptaIn Ladakh, which has a cold and arid climate and minimal annual rainfall of about 86.8mm (3.4in), 80% of the region's farmers depend on the glaciers to irrigate their crops. Over the past 30 years, there has been a significant decrease in snowfall, leading to reduced snow cover and resulting in retreating glaciers, insufficient stream water and severe water shortages in Himalayan villages.

But in Dolkar's village, one local engineer is combatting this glacier crisis using an innovative technique.

Referred to as the "Ice Man of Ladakh", Chewang Norphel has successfully constructed an artificial glacier in Nang, a village near to Thiksey.

As part of his job, Norphel traveled to various villages to address their issues. During those visits he discovered that 80% were farmers who are heavily reliant on water. Glacial meltwater, crucial for farming, only starts flowing in mid-June, while the sowing season begins in April. Due to long winters, the unused meltwater flows into rivers. To conserve this vital resource for the communities, Norphel decided to create an artificial glacier. He built artificial glaciers in 10 other villages in the Ladakh region.

Nang village is one of them. Located approximately 30km (18.6 miles) from Leh town in the Ladakh region, Nang sits at an altitude of 3,780m (12,402ft) above sea level, and is home to just 334 people. The primary livelihood in Nang is agriculture, with the main crops being potato and wheat.

As with many villages in the region, there is no permanent glacier in Nang and the water supply is fed by natural springs and streams. However, the water is not enough to meet the needs of farmers, especially during the crucial sowing season in April and May. This presents a challenge for agriculture, especially in irrigating fields of wheat, potatoes and other crops during spring, as the glacial melt doesn't occur until summer.

Facing uncertain weather patterns, farmers grappled with the dilemma of planning their agricultural activities for the following year. The unpredictability left them unsure whether to sow for the upcoming season or not. While not planting posed a risk of potential income loss, proceeding with sowing raised concerns about the availability of water resources.

Witnessing the climate impacts his community was facing, 87-year-old Norphel, an engineer and former rural development officer, came up with an innovative technique that prevents farmers from facing a shortfall in their yields and brings glaciers closer to their village.

"The main glacier starts giving water only in the month of June," says Norphel. "We can't make water. So our only option is to use the source available to us."

Norphel says the idea to use glacier water as a resource came to him where he least expected it: a garden tap behind his house. "We keep the taps running in winter to keep the water flowing," he says. "Otherwise the water freezes in pipes and risks bursting." This water, however, usually just drains away. Norphel observed a small patch of thin ice that had formed under one of his running taps. The water had pooled under a shady area and frozen over, as it was away from direct sunshine. He realised if he could capture and freeze the wasted water, he could create an artificial glacier for the entire village.

Kanika Gupta

Kanika GuptaNorphel strategically constructed multiple glaciers at different altitudes – which would all work towards benefitting one village. The glacier closest to the village, positioned at the lowest altitude, melts first, providing essential irrigation water during the initial sowing period in the spring. As temperatures rise, the subsequent glacier at a higher altitude begins to melt, ensuring a continuous and timed supply of irrigation water to the fields below.

The ice wall technique

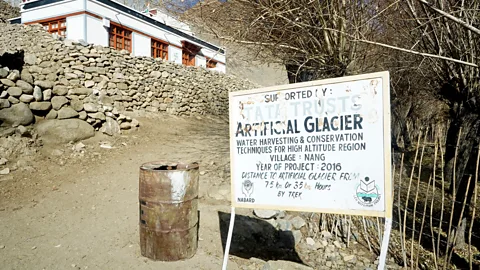

Nang village is nestled under towering mountains, and welcomes its visitors with a board, which points towards Norphel's now-famous artificial glacier.

The glacier is a 30-minute scramble up the region's characteristic mountainsides. Patches of ice start to appear within the first 10 minutes.

Suryanarayanan Balasubramanian is the co-founder of Acres of Ice, a company providing water management solutions, including artificial glaciers. He is working on a PhD on artificial ice reservoirs at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland and is currently researching how the ice glacier can lead to increased water conservation.

Kanika Gupta

Kanika Gupta"The village employs a unique water storage structure involving a frozen canal atop the mountain that extends into the valley," says Balasubramanian, who has spent time in Nang village. "Rock walls strategically placed along the canal break the water speed, enhancing the chances of freezing. The purpose of these rock walls is to increase the freezing rate, resulting in the creation of ice sheets across the valley."

The innovative approach has been successful, Balasubramanian says. According to him, the village's water supply has increased by up to 20%.

"As of today, this glacier is benefiting about 10 villages by supplying them water in the crucial months of April. We are building two more. It is also a very good solution to recharge groundwater that is rapidly receding due to over-tourism in Ladakh," says Norphel.

Farmers in Nang are thankful for the glacier that has improved their access to water significantly.

"Before we had the artificial glacier, getting enough water was hard for us," says Rigzen Wangyal, a 44-year-old farmer from Nang village. "Even though there was a lot of snow, it fell far away. It took a long time to melt, and even longer to come to us. This delay meant our harvests were late, and sometimes our farms became dry because we didn't have enough water."

Wangyal was one of the initial team members recruited in 2013 by Leh Nutrition Program (LNP), a local non-profit responsible for the implementation of these artificial glacier projects in the villages of Ladakh. "We just carried a shovel and worked in subzero temperatures to divert the flow of water," he recalls. "I didn't even have warm shoes at the time, but I did it for the community. Now the artificial glaciers are our first source of water."

Norphel, who began working with the non-profit in 1995, so he could expand his artificial glacier programme more efficiently, has earned numerous accolades for his achievements, including the Padma Shri, one of the biggest civilian awards in India. His innovative concept has served as inspiration for other projects, such as Sonam Wangchuk's Ice Stupa in Ladakh, where frozen water adopts the shape of a conical stupa before thawing and being distributed during the cultivation season. However, Norphel views Wangchuk's creation with a degree of scepticism.

"Ice Stupas are also a solution, and you don't have to choose the site carefully [unlike glaciers]. However, they are also very expensive and complicated compared to artificial glaciers, which are simple and low-cost."

Local solution to a global problem

Artificial glaciers are a potent water resource management strategy, experts say. While they may not resolve the global glacier melting problem, they can effectively address the challenges faced by numerous communities worldwide that heavily depend on glaciers.

"It is a very clever idea," says David Rounce, assistant professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering at Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania, US, whose recent paper reveals the world risks losing between 25% and 40% of glacier mass by the end of the 21st Century.

Kanika Gupta

Kanika Gupta"The methods being used in these regions, like ice stupas and glaciers, seem to work well," says Rounce. "They can store a lot of water, providing valuable freshwater resources for communities in the high mountains. But when we think about the problem, it is that the temperature is only going to continue increasing unless we take action as a global society."

Nepal's International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), an intergovernmental organisation working on climate resiliency in the Himalayas, recently released a report warning policymakers they needed to prepare for the "cascading impacts" of climate change in the region. There will be "grave consequences" for human life, and nature, the report concluded.

"With two billion people in Asia reliant on the water that glaciers and snow here hold, the consequences of losing this cryosphere are too vast to contemplate," Izabella Koziell, deputy director general of ICIMOD, said. "We need leaders to act now to prevent catastrophe."

Rounce's 2023 study underscores the importance of small glaciers in supplying water and sustaining the livelihoods of millions, especially in regions like central Europe and high-mountain Asia. These smaller glaciers are pivotal to the societies and economies of mountain communities, such as those in Nang and Thiskey, says Rounce.

"Considering [Norphel's] technique globally is crucial because many communities worldwide, such as those in Chile and Central Europe, rely on these water resources. Therefore, it can be an effective local solution for various global communities facing water-related challenges," he says.

More like this:

• The drought that forced a Himalayan village in Nepal to relocate

However, as Rounce highlights, these small-scale projects are mitigation techniques, rather than climate solutions. "Thinking that these are going to prevent the loss of glaciers globally. That's not going to happen, unfortunately."

Norphel believes that his simple, low-cost technique is a long-lasting method.

"We can't create water, but we can make use of the sources available. By involving village people, we can train able individuals to handle maintenance themselves. These artificial glaciers also help regenerate streams in villages, becoming a crucial secondary water source."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday. Click here for the BBC’s full range of newsletters available outside of the UK.